The battles Shaolin monks fought are only part of their story. Just as important is the quieter, longer legacy they left behind: the techniques they codified, the soldiers they helped train, the villages they protected, and the myths that turned “Shaolin” into a symbol of Chinese martial excellence.

This section looks beyond individual engagements to explore how Shaolin monks influenced martial arts, state defense, and the wider imagination, from the Ming dynasty to the modern day.

Codifying Martial Arts and Weapon Techniques

Shaolin is best known today for its forms and weapons — and that reputation is rooted in real historical influence.

Over centuries, the monks developed a sophisticated curriculum, but one area stood out above all: the staff. Their staff-fighting methods became legendary, precise enough and effective enough that military leaders sought them out.

In the 16th century, during the Ming dynasty’s struggle against coastal pirates, the famous general Qi Jiguang consulted Shaolin monks while redesigning his army’s boxing drills and weapons training. He needed practical, efficient methods to prepare troops for brutal, real-world combat, and Shaolin’s training proved useful.

Another general, Yu Dayou, is also said to have visited the Shaolin Temple specifically for martial instruction, further cementing the temple’s status as a place where serious fighting skills could be learned and refined.

The monks’ staff techniques were considered so valuable that they were written down and circulated beyond the monastery. One key example is Cheng Zongyou’s 1610 treatise, often referred to as the “Shaolin Staff Method”, which set out Shaolin staff principles in systematic form. Manuals like this transformed temple practice into portable doctrine, allowing Ming soldiers and martial artists elsewhere to study Shaolin methods in detail.

By the late Ming, Shaolin’s reputation was no longer limited to weapons. Its empty-hand boxing (quan) had developed enough to be recognized in its own right, adding to the growing canon of Chinese martial arts and shaping how later generations would understand “Shaolin kung fu” as a complete system — not just a set of techniques, but a model of disciplined training.

Military and Paramilitary Roles

Shaolin’s influence on warfare wasn’t confined to what happened inside the courtyard.

At several points in Chinese history, Shaolin monks were effectively woven into the state’s defense structure. After Li Shimin’s victory in 621 (with the Shaolin monks’ help), the temple received imperial favor — and, importantly, permission to maintain armed monks. Over time, the temple even established branch monasteries with monk-soldiers that could assist local authorities when needed.

During the Tang and later the Ming, imperial officials recognized that Shaolin’s warriors could serve as a reliable auxiliary force in emergencies. When bandits, rebels, or pirates threatened the realm, the government sometimes turned to the Shaolin Temple, recruiting monks to fight or to reinforce regular troops.

In the mid-Ming, this relationship became especially visible. The court directly enlisted Shaolin monks in imperial campaigns—records mention at least six separate wars in which Shaolin fighting monks took part after the pirate conflicts of the 1550s. Their decisive victory over the Wokou pirates in 1553, where Shaolin monk-soldiers annihilated a pirate force with minimal losses, impressed the emperor enough that the temple was rewarded with monuments, repairs, and tax privileges.

At the same time, the Shaolin Temple became a magnet for martial talent. Lay practitioners, officers, and even high-ranking generals visited to exchange techniques and observe the monks’ training. In this way, the temple functioned as both a monastery and a military academy, its practices seeping gradually into wider Chinese martial culture.

But this visibility had a cost. As centuries passed, some rulers grew uneasy about the idea of a powerful, autonomous “monk army.” By the Qing dynasty, the imperial attitude had cooled. The emperors encouraged Shaolin monks to focus on religious activity, and at one point banned monastic martial training outright in an attempt to prevent the rise of rebel forces organized around martial temples. The court wanted Shaolin’s spiritual authority — not its potential as an armed faction.

Local Defense and Militia Tradition

Beyond formal imperial campaigns, Shaolin monks often acted as practical guardians of their immediate region. Whenever central authority weakened, the temple’s martial side became a local lifeline.

This tradition goes back early. During the Sui dynasty, Emperor Wendi granted the Shaolin Temple a substantial estate and mill in Baigu Valley. One likely reason was simple: the monks could secure that land in turbulent times, serving as stabilizing figures in an area prone to unrest.

Across the centuries, a familiar pattern repeats: when bandits, rebels, or invaders appeared and official troops were absent or unreliable, Shaolin’s monks stepped in. The 610s saw them defending the monastery itself from raiding bandits. In the 1550s, they fought pirates along the coast. In the 20th century, they went so far as to form a local militia to keep order amid warlord-era chaos and Republican instability.

By 1912–1920, as the Qing collapsed and the Republic struggled to assert control, local authorities officially recognized this role. Monk Yunsong Henglin was appointed head of a Shaolin Militia Guarding Corps, tasked with training younger monks, arming them, and organizing patrols. During the famine years of 1920, when starving bandits menaced nearby villages, this militia carried out multiple successful defensive operations, earning a reputation for restoring “peace and the ability to work” in the surrounding communities.

Over time, the image of “monk patrols” — monks walking the roads with staffs or simple weapons, keeping watch over farms and villages — became part of Shaolin’s identity. The temple was not just a religious center, but a martial institution with a social responsibility, stepping in where the state was weak or absent.

Legacy in Martial Arts Lineages and Global Imagination

Perhaps Shaolin’s most enduring legacy is neither a battle nor a book, but a symbol.

By the late imperial period, many martial arts schools — especially in southern China — claimed to trace their lineage back to Shaolin Temple. Some did so accurately; others likely embroidered the connection. The legendary “Five Elders” story is at the heart of many of these claims: according to popular lore, five Shaolin masters survived a Qing-era destruction of the temple and fled south, founding new styles such as Wing Chun, Hung Gar, and Choy Gar.

Historically, that particular story belongs more to myth and secret society lore than documented fact. Yet its spread tells us something important: “Shaolin” had become shorthand for martial excellence, resistance, and spiritual strength. To say a style was “from Shaolin” was to claim prestige and legitimacy.

The phrase “Shaolin style” gradually came to denote a broad family of external (hard) Chinese martial arts — strong stances, powerful strikes, vigorous forms — whether or not a given school had a direct genealogical tie to the temple.

In the 20th century, the Chinese government and martial arts organizations also leaned into Shaolin’s symbolic power. Shaolin’s past military service — especially against invaders and pirates — was repackaged as a source of national pride and physical culture. In the 1930s, for example, a “Return to Shaolin” martial arts demonstration was organized to celebrate how Shaolin kung fu had once defended China and could now help strengthen the people again.

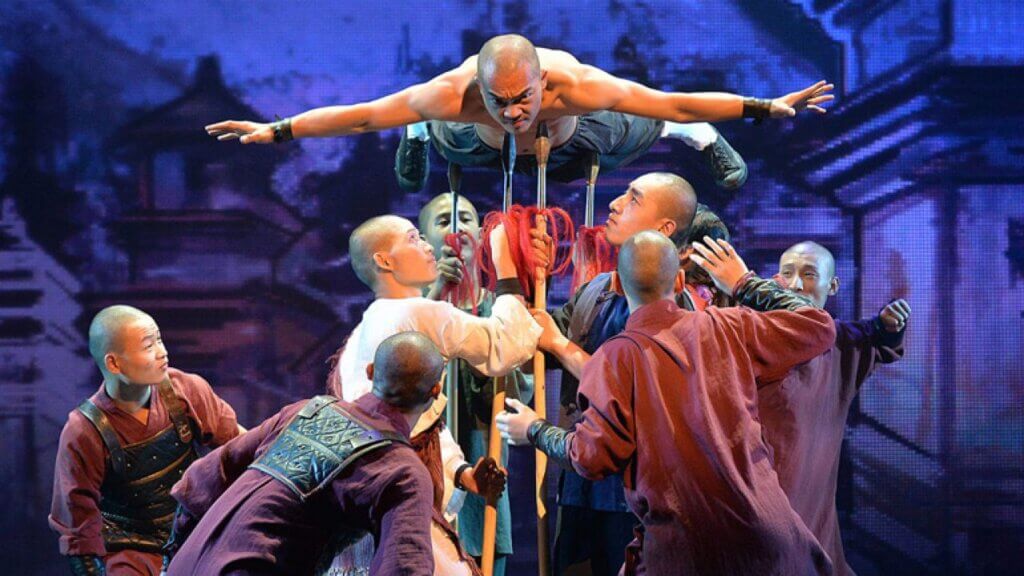

Today, Shaolin’s influence is truly global. Modern Shaolin warrior-monks perform on international stages and tours, showcasing both traditional forms and theatrical adaptations. Around the world, kung fu schools and wǔ guǎn (dojos) teach techniques and training methods inspired — directly or indirectly — by Shaolin curriculum. Films, novels, and documentaries have turned the “warrior monk” into an instantly recognizable archetype: someone who combines spiritual discipline, ethical restraint, and formidable combat skill.

That archetype — and the real practices behind it — may be Shaolin’s greatest contribution to world martial culture: a vision of training where body, mind, and moral purpose are all part of the same path.