Buddhism, one of the world’s major religions, has played a significant role in shaping the spiritual landscape of China for over two millennia. Introduced from India, Buddhism underwent a remarkable journey of adaptation, assimilation, and integration within Chinese society, leaving an indelible mark on its culture, philosophy, and religious practices. In this article, we explore the rich history, diverse traditions, and enduring legacy of Buddhism in China.

Early Transmission and Development

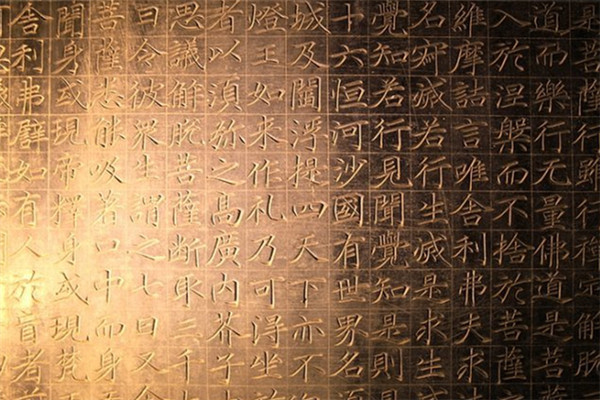

Buddhism first arrived in China via the Silk Road during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), gaining traction among intellectuals, merchants, and the imperial court. Early Buddhist texts were translated into Chinese, laying the foundation for the dissemination of Buddhist teachings across the empire. The spread of Buddhism was facilitated by the patronage of rulers such as Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire and Emperor Ming of the Eastern Han Dynasty, who supported the construction of monasteries and the establishment of Buddhist communities.

Integration and Syncretism

As Buddhism took root in China, it underwent a process of syncretism, blending with indigenous religious beliefs, Daoist practices, and Confucian ethics. This syncretic approach gave rise to unique schools of Chinese Buddhism, such as Chan (Zen), Pure Land, and Tiantai (Tendai), each emphasizing different paths to enlightenment.

Chan Buddhism, in particular, emphasized meditation and direct experience of awakening, while Pure Land Buddhism focused on devotion to Amitabha Buddha and rebirth in the Pure Land.

- Mahayana Buddhism: Mahayana, or “Great Vehicle,” Buddhism emphasizes compassion, wisdom, and the aspiration to attain Buddhahood for the benefit of all beings. Mahayana texts, such as the Lotus Sutra and the Heart Sutra, have profoundly influenced Chinese Buddhist thought and practice.

- Chan Buddhism: Chan, known as Zen in Japan, is a school of Buddhism that emphasizes meditation (zazen) as a direct means of awakening to one’s true nature. Chan Buddhism has had a profound impact on Chinese culture, art, and literature, inspiring the creation of iconic works such as the Platform Sutra and the Blue Cliff Record.

- Pure Land Buddhism: Pure Land Buddhism centers around devotion to Amitabha Buddha and the aspiration to be reborn in his Pure Land, a realm of bliss and liberation. Pure Land practices, such as reciting the name of Amitabha Buddha (nianfo), have been popular among Chinese Buddhists seeking rebirth in the Pure Land.

Golden Age of Buddhism

The Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) is often regarded as the golden age of Buddhism in China, marked by a flourishing of monastic institutions, artistic expression, and intellectual exchange. Buddhist monks and scholars from India, Central Asia, and Korea traveled to China, contributing to the translation of Buddhist scriptures, the development of new philosophical schools, and the propagation of Buddhist teachings. Monastic centers such as the Shaolin Temple became renowned for their scholarly pursuits, martial arts training, and contributions to Chinese culture.

Persecution and Revival

Despite its widespread popularity, Buddhism faced periods of persecution and suppression during the Tang and subsequent dynasties. The Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution of the Tang Dynasty and later campaigns by Confucian scholars and rulers led to the destruction of monasteries, confiscation of Buddhist properties, and loss of patronage. However, Buddhism experienced a revival during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), with the emergence of new sects like Chan Buddhism and Pure Land Buddhism, as well as the patronage of emperors and literati.

Modern Practices and Revitalization

In modern China, Buddhism continues to hold a significant place in the spiritual landscape, navigating a dynamic relationship with the government and societal changes. While the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) brought challenges to religious practices, including Buddhism, the post-Mao era witnessed a resurgence of interest in Buddhist teachings and rituals. Today, Buddhism in China operates within a framework of government oversight, with the state recognizing it as one of the five official religions under regulated supervision. This framework aims to maintain social harmony and ensure religious practices align with national policies.

As a result, Buddhism continues to thrive in China, with millions of adherents engaging in daily rituals, temple visits, and religious festivals. In fact, research suggests up to 33% of the population identifies as Buddhist. Urban centers like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou boast bustling Buddhist communities, while historic sites such as the Shaolin Temple and Mount Wutai draw pilgrims and tourists seeking spiritual enlightenment and cultural heritage. Moreover, the internet has provided a platform for Buddhist teachings to reach a wider audience, with online forums, websites, and social media channels disseminating religious texts, lectures, and mindfulness practices to millions of followers across the country.

In this modern context, Buddhism in China faces both challenges and opportunities. While economic prosperity and technological advancement have brought new avenues for spreading Buddhist teachings, they have also led to materialism, consumerism, and secularism, posing challenges to the preservation of traditional values and practices. Nevertheless, Buddhism remains a resilient and adaptive force, offering solace, guidance, and a sense of community to believers amidst the complexities of modern life in China.

Impact and Influence

The influence of Buddhism on Chinese culture extends far beyond religious practices. It permeates literature, poetry, calligraphy, medicine, and martial arts, shaping the values, aesthetics, and worldview of successive generations. Buddhist principles of compassion, mindfulness, and impermanence continue to resonate with people from all walks of life, offering solace, inspiration, and guidance in a rapidly changing world.

Key Figures and Texts

Throughout its history in China, Buddhism has been shaped by the teachings of eminent monks, scholars, and masters. Figures such as Bodhidharma, Huineng, and Xuanzang played pivotal roles in transmitting and interpreting Buddhist doctrines, while texts like the Diamond Sutra, Heart Sutra, and Lotus Sutra became foundational scriptures for Chinese Buddhists.

Art and Architecture

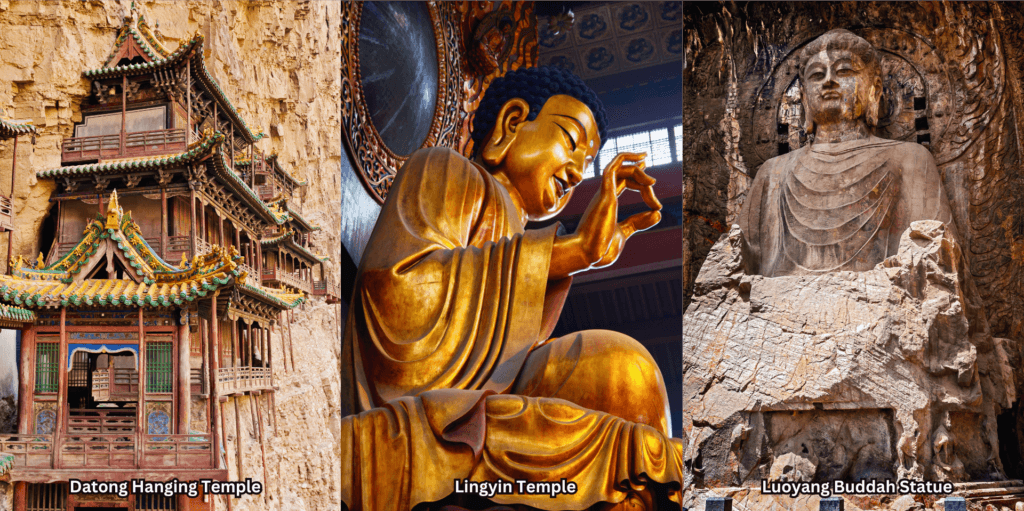

Buddhism in China flourished not only in philosophy and practice but also in art and architecture. Buddhist art, characterized by intricate sculptures, paintings, and murals, adorned temples and caves, depicting scenes from the life of the Buddha, bodhisattvas, and celestial beings. Architectural marvels like the Mogao Caves, Longmen Grottoes, and Shaolin Temple stand as testament to the enduring legacy of Buddhist craftsmanship and devotion.

Conclusion

The journey of Buddhism in China is a testament to the resilience, adaptability, and enduring appeal of this ancient spiritual tradition. From its humble beginnings to its widespread influence across Chinese society, Buddhism has left an indelible mark on the cultural, philosophical, and religious landscape of China. As Buddhism continues to evolve and adapt to the challenges of the modern world, its teachings of compassion, wisdom, and inner peace remain a source of inspiration and guidance for millions of practitioners in China and beyond.