Introduction

In Avatar: The Last Airbender, the Air Nomads are a people of swirling robes, shaved heads, and serene smiles – peaceful monks who can whip up tornadoes. Avatar Aang, the last Air Nomad, spends much of the series exemplifying the gentle, free-spirited ethos of his people even as he wields tremendous power. Both children and adults are enchanted by the Air Nomads’ blend of spirituality and martial arts. But did you know that the creators drew heavily from real-world monastic traditions and philosophies to shape the Air Nomads? From the Kung Fu monks of Shaolin Temple to the wisdom of Daoist sages and the pacifist teachings of Buddhism, the Air Nomads’ culture has deep roots in our world.

Spoiler Warning:

This article contains detailed discussion of storylines, characters, and lore from Avatar: The Last Airbender, The Legend of Korra, and minor points related to the comics and novels. If you haven’t finished the series and wish to avoid spoilers, we recommend returning to this piece after watching both shows.

Air.

“Air is the element of freedom. The Air Nomads detached themselves from worldly concerns and found peace and freedom.“

-Iroh

The Air Nomads: Monks of the Four Nations

In the Avatar world’s mythology, the Air Nomads are one of the four nations, distinguished by their entirely monastic society. Unlike the Earth Kingdom, Fire Nation, or Water Tribes, the Air Nomads had no kings, no nobles, and in fact no laypeople at all – every Air Nomad was raised as a monk or nun within their order. They lived in remote Air Temples at the edges of the world, high atop mountain ranges or clinging under cliffs, secluded from worldly distractions. There were four such temples (Northern, Southern, Eastern, Western), and they were segregated by gender: historically, male monks resided in the Northern and Southern Air Temples, while female nuns lived in the Eastern and Western Air Temples. Despite these fixed temple locations, the term “Nomads” is fitting – Air Nomads were wanderers by nature. They frequently traveled the world on the backs of flying bison, their lifelong animal companions, to see distant lands or embark on spiritual journeys. In fact, classical Air Nomad culture encouraged an itinerant lifestyle, preferring the freedom of the open sky over attachment to any one place

The Air Nomads were known as the most spiritual of all peoples. In the world of Avatar, bending ability is tied to spirituality, and fittingly every Air Nomad was an airbender – a unique case among the four nations. From a young age, Air Nomad children learned airbending alongside meditation, treating the bending arts as an extension of their spiritual practice. We see this with Aang, who as a boy at the Southern Air Temple studied under monks like Gyatso. The Air Nomads valued simple living, humility, and joy. They had a small population and economy, sustained by gardening and harvesting fruit in the mountains, and they eschewed material wealth. Their culture prized altruism and detachment from worldly affairs, reflecting a belief that true freedom comes from letting go of greed and ambition. Uncle Iroh, in one memorable lesson to his nephew Zuko, described it well: “Air is the element of freedom. The Air Nomads detached themselves from worldly concerns and found peace and freedom.” Indeed, the Air Nomads’ peaceful nature and love of freedom are core to their identity.

Despite their tranquility, the Air Nomads were not naïve about the world. Different historical eras saw them alternate between isolation and engagement. At times they withdrew almost completely, wary of being drawn into the violence that plagued other nations. In other eras, Air Nomad monks left their temples to help those in need, acting as wandering peacemakers and teachers across the world. In The Legend of Korra, we see a reborn Air Nation embrace this role. Tenzin – Aang’s son and a master airbender – leads a new generation of Air Nomads who travel around the Earth Kingdom aiding communities and spreading peace after the chaos of the Equalist and Red Lotus conflicts. He proclaims that the Air Nomads will roam the world to “help people of all nations”, echoing the Air Nomads’ ancient altruistic missions. This development shows the enduring ideal that Air Nomads serve a higher purpose beyond themselves, much like benevolent monks or sages in real history.

It’s also worth noting that the Air Nomads had a playful side. The show often illustrates that these monks were fun-loving and had a great sense of humor, as Iroh also quipped. In the episode “The Southern Air Temple,” we see flashbacks of Monk Gyatso and young Aang sneaking custard pies from the kitchen and playfully airbending them onto the other elders – a prankish training game that left Aang in fits of laughter. Aang himself carries this light-hearted spirit throughout the series, delighting in games like air scooter racing or pelting his friends with fruit pies via airbending. This reflects a cultural belief that laughter and joy are also part of spiritual balance. The Air Nomads’ approach to life was not stern asceticism, but warm and joyful. They believed in living with a smile, showing kindness to all, and not taking oneself too seriously – qualities that endeared Aang to friends and viewers alike.

Spiritual Philosophy of the Air Nomads

At the heart of Air Nomad culture are spiritual principles that closely parallel real-world Eastern philosophies. The Air Nomads’ guiding element Air is associated with freedom, detachment, and harmony. They teach that one can only be truly free by letting go of earthly attachments. This theme is echoed powerfully in Aang’s personal journey. During Aang’s training with Guru Pathik to unlock the Avatar State, the guru guides him through unlocking chakras (a concept borrowed from Hindu and Buddhist traditions) and stresses letting go of fear and attachment – including Aang’s deep attachment to his friend Katara – as the final step to gain cosmic energy. Aang struggles with this, showing how challenging the Air Nomad ideal of non-attachment can be when it conflicts with personal love. This idea of releasing attachments comes straight from Buddhist philosophy: monks renounce family ties and possessions to achieve spiritual enlightenment. In the show, it’s dramatized as the key to unlocking the Avatar’s ultimate spiritual power. The inclusion of the chakra meditation in Aang’s training is one of the overt nods to Hindu-Buddhist influence in Avatar, underscoring that the Avatar world’s spirituality is interwoven with real practices.

Another pillar of Air Nomad philosophy is ahimsa, or nonviolence. The Air Nomads are pacifists who generally refuse to harm living being. Aang exemplifies this ethos: he is a vegetarian and is horrified when he finds out Sokka has been eating meat jerky in his Air Temple! He also faces a serious moral dilemma in the finale when he must stop Fire Lord Ozai: to kill, as urged by friends and his past Avatar incarnations, or not to kill. Thus he comes up with a novel solution: removing Ozai’s firebending ability without killing him. This resolution – Energybending – allows Aang to stay true to the Air Nomads’ doctrine of nonviolence while still fulfilling his Avatar duty. His decision mirrors the Dharmic principle of ahimsa, revered in Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism, which holds all life sacred. In real monastic orders, strict monks will even avoid stepping on insects and practice vegetarianism out of compassion. The show repeatedly shows Air Nomads (Aang and later Tenzin) finding creative, pacifist ways to resolve conflict, highlighting that for an Airbender, the highest victory is one won without cruelty or killing.

The Air Nomads’ spirituality emphasizes detachment and inner peace. They intentionally separated from worldly politics and lived simple lives of meditation, gardening, and prayer. As Iroh noted, they “found peace and freedom” by detaching from worldly concerns. For example, Air Nomads owned little – Aang essentially carries just his staff/glider and a few relics. They didn’t use money among themselves; commerce was minimal in their lifestyle. This echoes the simplicity of Buddhist monastic life, where monks vow poverty and rely on charity. Interestingly, the Air Nomads would only eat meat if it was truly offered to them as charity (and even then many chose to abstain entirely), reflecting the Buddhist idea that monks should accept whatever food is given in alms rather than be picky – but also that causing an animal’s death intentionally is to be avoided. In practice, Aang sticks to vegetarian meals like salads and fruit pies; the show plays this for humor at times, but it’s a serious part of his identity.

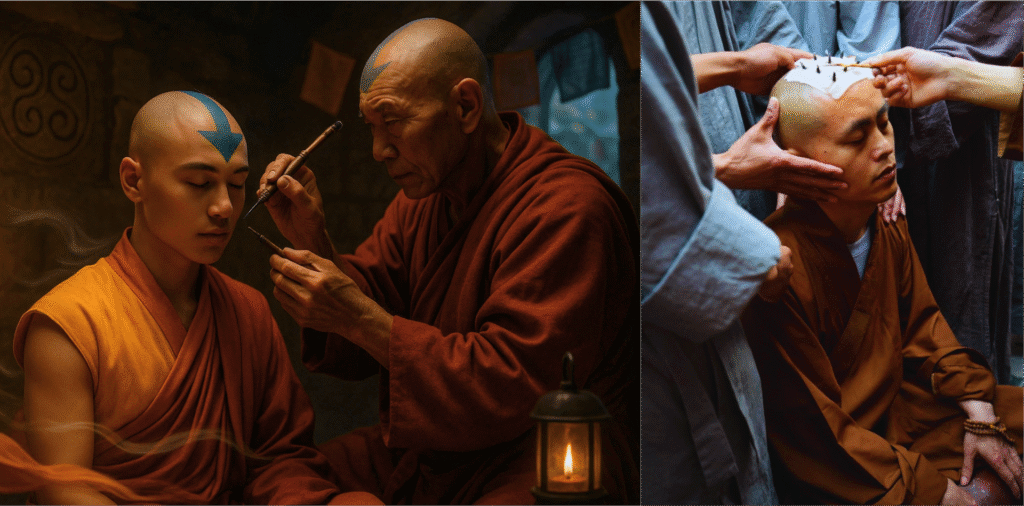

The Arrow Tattoos that adult Airbenders sport are another spiritual facet of their culture. Aang’s iconic blue arrow tattoos, which glow when he enters the Avatar State, mark him as an Airbending master. In Air Nomad tradition, a young airbender receives their tattoos only after achieving mastery of the art – Aang earned his at just 12 years old after inventing a new airbending technique (the air scooter). The arrow design itself is modeled after the markings of the sky bison (the original airbenders), symbolizing the Air Nomads’ bond with these creatures. The tattoos serve almost like a monk’s prayer beads or a black belt in martial arts – a visible sign of spiritual and physical attainment. Real Buddhist monks don’t have arrow tattoos, of course, (though some do sport jie ba markings on their heads) but the concept of marking a rite of passage is universal. Interestingly, among the Air Nomads shaving one’s head was optional, unlike in real monasteries where it’s required – male monks shaved their heads fully, while female nuns only shaved their forehead enough to show the arrow tattoo on the forehead. This detail, while small, shows the creators paid attention to monastic customs but adapted them for the Air Nomads’ distinct aesthetic.

Perhaps the greatest spiritual legend of the Air Nomads is Guru Laghima, an ancient Air Nomad guru who achieved a state of enlightenment so profound that (according to lore) he became weightless and could fly without glider or wings. In The Legend of Korra, the villain Zaheer, who is deeply obsessed with Air Nomad teachings, and later gains the ability of weightlessness himself, recites Laghima’s famous poem: “Let go your earthly tether. Enter the void. Empty, and become wind.” This line encapsulates Air Nomad spirituality – by letting go of all earthly attachments (“tethers”), one can achieve ultimate freedom (“the void”) and literally become one with the wind. While Zaheer is an antagonist, his arc demonstrates the powerful spiritual potential of Air Nomad teachings. The idea of enlightened monks able to levitate is found in many religious legends (for instance, some Buddhist and Daoist sages are said to defy gravity in stories). Through Guru Laghima’s lore, Avatar’s writers paid homage to these mystical tales, suggesting that the Air Nomads’ spirituality, taken to its peak, transcends even the physical laws of the world. For the Air Nomads, airbending was never just about combat – it was a path to spiritual freedom.

The Martial Art of Airbending

Although the Air Nomads were pacifists, they were still formidable airbenders with a distinct fighting style. In the series, airbending is depicted as graceful, defensive, and fluid – full of evasive maneuvers, spiraling movements, and sudden gusts that redirect an opponent’s force. Aang rarely meets an attack head-on; instead he dances around enemies, using blasts of wind to trip or push them rather than strike directly. This choreography isn’t just fantasy – it was directly based on a real martial art form known as Baguazhang (八卦掌), or “Eight Trigram Palm.” The creators of Avatar consulted a martial arts expert, Sifu Kisu, to give each bending art a real-world martial arts foundation. For airbending, Baguazhang was the perfect fit. This Chinese martial art is famous for its circle walking technique, where the practitioner continuously moves in a circular path, flowing around the opponent. Bagua emphasizes agility, constant motion, and using the whole body in a dynamic, circular way – exactly how airbending looks in the show. If you watch an experienced Baguazhang artist and compare it to Aang’s movements, you’ll notice the similarity in the footwork and the way strikes are delivered with open palms and fluid arm sweeps.

Key traits of airbending’s martial style (Baguazhang):

- Circular Footwork: Airbenders never stay still in battle; they glide, sidestep, and run rings around opponents. This is straight from Bagua’s circle walking drills, which train one to evade and flank an adversary. Aang, for example, often literally runs in circles around Zuko or Azula, a strategy that confuses aggressors.

- Redirection and Deflection: Rather than brute force, airbending uses an attacker’s energy against them. Aang might leap out of the way of an attack and conjure a gust to send the foe stumbling past. This reflects the internal martial arts philosophy (shared by Tai Chi and others) of yielding to force and then leading it away – very similiar to the Daoist idea of “bending like the reed in the wind”.

- Light, Agile Stances: Baguazhang fighters stay on the balls of their feet, ready to move at a moment’s notice. We see airbenders adopt narrow stances, often one foot poised forward lightly. This agility allows quick dodges and acrobatics. Airbending combat often looks like acrobatic dance – consider Aang’s tendency to somersault and spring off walls. This acrobatic flair was emphasized even more in The Legend of Korra during the Airbender vs. Equalist fights, where new airbenders like Kai showed off flips and spins mid-air, and Tenzin battled with gracefully evasive techniques.

- Defensive Techniques: In the franchise, airbending is almost never used to deliver a lethal blow. Instead we see techniques like air shields, turbulence to unbalance foes, or gentle gusts to swat weapons out of enemies’ hands. Even the famous Air Scooters (balls of air Aang and other airbenders ride) can be used to knock people over harmlessly. This defensive style aligns with the Air Nomads’ pacifism – they developed their bending as an art form and for self-defense or diversion, not for aggression. As an example, Aang creates a massive air dome in his fight with Fire Lord Ozai purely to block Ozai’s fire blasts without harming him.

It’s fascinating that the show’s firebending was based on Northern Shaolin Kung Fu (an aggressive style of rapid kicks and punches), earthbending on the strong stances of Hung Gar Kung Fu, and waterbending on the flowing movements of Tai Chi. Each element’s bending corresponds to a different real martial art. Airbending’s connection to Baguazhang makes it a fitting martial art for the Air Nomads: circular motion, yielding, and redirection are all central themes. While often associated with Daoist imagery—like the eight trigrams of the I-Ching and the yin-yang symbol—Bagua itself originates from Chinese folk tradition, not directly from Daoism. The I-Ching, too, predates formal Daoism and has been used across multiple belief systems, including folk religion, Confucianism, and Daoist practice. Despite these distinctions, the symbolic resonance of Bagua—constant change, harmony with natural forces, and motion through stillness—beautifully reflects the Air Nomads’ spiritual and martial identity. In Daoism in particular, air and wind are often metaphors for the unseen force of the Dao and the virtue of yielding. Bagua practitioners even sometimes train with the imagery of walking in the patterns of a yin-yang symbol. So when Aang spins around an opponent in a circle and, with a gentle push of air, sends them flying, it’s as if a little bit of ancient Chinese folk wisdom has come to life in a kid-friendly cartoon form.

It’s also worth noting that the Shaolin warrior monks likely inspired aspects of Air Nomad martial culture beyond just the specific bending style. The very idea of monks who practice martial arts has a strong precedent in the famed Shaolin Temple in China, where Buddhist monks have trained in Kung Fu for centuries. The Air Nomads can be seen as a fantasy reimagining of Shaolin monks: Aang’s season one and two outfit – the saffron-yellow and orange monk robes with one shoulder bare – directly parallels the robes worn by the Shaolin monks (which in turn were inspired by Indian Buddhist monk robes). Just like Shaolin monks, the Air Nomads integrated physical discipline with spiritual practice. They probably had forms and exercises to practice airbending every day at the temple, akin to how Shaolin monks perform daily kung fu forms at sunrise. The show even alludes to “airbending training gates” and other contraptions in the temples, similar to how a Shaolin temple might have wooden dummies or weapons stands. And the concept of elder monks as mentors (Monk Gyatso to Aang) feels very much like the master-student relationships in real martial arts monasteries. So while airbending’s move-set is Bagua, the ethos of a peaceful monk-warrior is pure Shaolin. This mix of influences makes airbending a beautiful example of art imitating life – it’s fictional bending magic, but grounded in the real moves and values of martial monk traditions.

Real-World Inspirations and Cultural Parallels

The richness of the Air Nomads is no accident – the show’s creators Bryan Konietzko and Michael Dante DiMartino deliberately wove in many threads from real cultures and spiritual practices to make the Air Nomads feel authentic. Let’s explore some of these real-world inspirations that shaped the Air Nomads:

Tibetan and Himalayan Buddhism: The primary model for the Air Nomads was the Buddhist monks of Tibet, Bhutan, and Nepal. Like Tibetan monks, Air Nomads live in monasteries perched high in the mountains, wear robes reminiscent of Tibetan monastic robes (Aang’s later outfit in Book 3 even resembles a Tibetan chuba, a traditional robe), and uphold pacifism and meditation as central practices. The very names “Gyatso” and “Tenzin” are direct references to the Dalai Lama – the 14th Dalai Lama’s name is Tenzin Gyatso! This is a fun Easter egg: Aang’s mentor was Monk Gyatso and Aang’s son is Tenzin, effectively splitting the Dalai Lama’s name across two characters. Additionally, the method by which Air Nomads identify the next Avatar – by having a child choose from among toys that belonged to past Avatars – is based on the Tibetan Buddhist method of finding the reincarnation of a high lama (like a Dalai Lama or Karmapa) by seeing if a child can recognize objects from their past life. These parallels firmly root the Air Nomads in Buddhist lore and lend a layer of spiritual legitimacy to the Avatar’s world-building.

Paro Taktsang (Tiger’s Nest) in Bhutan

Inspiration for Avatar: The Last Airbender‘s Western Air Temple

Chan Buddhism and Shaolin Monks: The Air Nomads also draw inspiration from the Shaolin Buddhist tradition of China. The Shaolin Temple is famed for its kung fu fighting monks who followed Chan (Zen) Buddhist teachings. The Air Nomads mirror this with their own blend of monkhood and martial arts mastery. Aang’s early outfits echo the orange robes of Shaolin monks, and the Air Nomad temples share design elements with real Chinese monasteries. For instance, the Western Air Temple (which hangs upside-down under a cliff) was inspired by Bhutanese cliffside monasteries and Paro Taktsang (Tiger’s Nest) in Bhutan, a sacred cliff monastery. Even the little details like architecture weren’t random – the spires and prayer towers at the Air Temples resemble pagodas, similar to the pagoda forest at the Shaolin Temple which contains monks’ stupas. The fusion of Shaolin imagery with Tibetan lifestyle produced the unique Air Nomad aesthetic: humble yet powerful, playful yet disciplined. It’s like taking the Shaolin monk archetype and giving them gliders and bison to ride!

Daoism (Taoism) and Chinese Philosophy: The ethos of the Air Nomads also resonates strongly with Daoist principles. Daoism values living in harmony with nature, simplicity, and the concept of wu wei (effortless action). The Air Nomads’ detachment from worldly concerns and pursuit of harmony mirrors Daoist sages who sought to live in accordance with the Dao (the natural way). In the show, King Bumi (though not an Air Nomad, he was Aang’s friend) demonstrates a very Daoist attitude with his mantra of “doing nothing” at times to let problems sort themselves – a philosophy explicitly noted in the influences as a nod to Lao Tzu’s teachings. Air Nomads embody the ever-changing, formless power of the wind, much like Daoist philosophy embraces change and the unseen forces of yin and yang. In the Avatar universe, the concept of balance between elements and the yin-yang symbolism (like the Ocean and Moon spirits representing a yin-yang pair) are directly lifted from Chinese thought. The Air Nomads contribute to balance by representing freedom and spirituality, a counterweight to the more material or aggressive nations.

Hinduism and Other Influences: While Buddhism and Daoism are most apparent, there are subtle hints of Hindu influence too. The idea of chakras used in Aang’s training comes from Hindu/Yogic philosophy, as Guru Pathik’s lessons show. The broader concept of the Avatar – a divine being reincarnating to restore balance – parallels the Hindu concept of an avatar (like the god Vishnu’s avatars) and the cycle of rebirth in Dharmic religions. In fact, Avatar as a word is Sanskrit for a deity’s earthly incarnation. The show’s cycle of the Avatar being reborn among the four nations is reminiscent of the cycle of samsara (rebirth) in Buddhism/Hinduism, combined with the Tibetan way of identifying reincarnated lamas. Additionally, the Air Nomads’ vegetarian tendencies and meditation are common to Hindu and Jain monks as well. The creators mention Sri Lankan Buddhism and early Mongolian Buddhism as influences too, indicating that they pulled from a wide spectrum of monastic traditions to craft a well-rounded fictional culture.

By blending all these influences, the creators made the Air Nomads feel both fantastical and familiar. Even younger viewers intuitively pick up on the monk vibe, sensing the Air Nomads are like “those real monks” they may have seen or heard about. Adult fans often dig deeper and discover these deliberate parallels – for example, that Aang’s staff reflects the Shaolin tradition of using the wooden staff — a weapon valued not for killing, but for its role in protecting life, disarming threats, and symbolizing discipline and peace. This layered design is what makes the Air Nomads so compelling. They are essentially a love letter to the idea of enlightened, kind monks across cultures, from the high lamas of Tibet to the kung fu masters of Shaolin to the wise hermits of Daoist legend. The show distills that idea into a fictional people who ride clouds and laugh easily – a people who feel true and inspiring.

Legacy and Lessons of the Air Nomads

Although the Air Nomads were tragically wiped out at the start of Avatar: The Last Airbender (a mass genocide by the Fire Nation, leaving Aang as the sole survivor), their legacy permeates the story and continues beyond it. Aang carries the Air Nomads’ teachings with him – in his gentle demeanor, in how he teaches others, and in how he resolves conflict. After the Hundred Year War, with Aang’s encouragement, an order of devotees called the Air Acolytes emerges, composed of non-benders who dedicate themselves to learning Air Nomad culture and philosophy. They preserve songs, prayers, and meditations, and eventually even take up residence in the refurbished Air Temples alongside Aang’s family and the new sky bison. This is a touching development: it shows that even without being born Air Nomads or having airbending abilities, people are inspired by the Air Nomads’ way of life. The Air Acolytes essentially become new monks and nuns, ensuring the Air Nomads’ cultural extinction was not absolute.

In The Legend of Korra, we witness a rebirth of the Air Nomads in a more literal sense. After a cosmic event known as Harmonic Convergence, new airbenders suddenly appear among ordinary people around the world. Tenzin, Aang’s son, travels to recruit these people – offering them a chance to train and follow Air Nomad teachings. Not all are immediately keen to shave their heads and don orange robes, of course; there’s a funny and poignant storyline as Tenzin tries to instill Air Nomad discipline in newcomers like the young thief Kai or the reluctant family man Ryu. Over time, though, many embrace the Air Nomad identity. Tenzin establishes training at the Northern Air Temple and on Air Temple Island (near Republic City), effectively rebuilding the Air Nomad society from scratch. It’s a rare and uplifting case of a nearly lost culture being revived. By the end of Korra’s third season, dozens of new Air Nomads don the traditional robes, receive tattoos upon mastery (Jinora, Tenzin’s daughter, proudly earns hers as a teenager), and take an oath to uphold the Nomads’ values. They even decide to resume the nomadic tradition of wandering the earth to help others, as mentioned earlier. This decision positions the new Air Nomads almost like global peacekeepers – not rulers or enforcers, but traveling sages who will assist and guide. It’s as if the Air Nomads have become the world’s spiritual conscience.

For both characters in the story and fans in the real world, the Air Nomads continue to teach important lessons. They show that strength doesn’t always mean aggression, and that one can be both gentle and powerful. Aang defeats the Fire Lord without killing; Tenzin fights off anarchists without ever losing his composure or values. The Air Nomads also demonstrate the value of maintaining one’s principles in the face of adversity. Even when nearly exterminated, their philosophy survives through Aang and is eventually rekindled in a new generation. This can be seen as a message of hope: cultures built on peace and wisdom can endure and regrow, even after immense tragedy.

Another subtle lesson from the Air Nomads is the idea of balance between spiritual and physical, between freedom and responsibility. Aang initially runs away from his responsibilities (fleeing the Southern Air Temple when he learns he’s the Avatar) because he fears losing his freedom. His journey is about learning to take up duty without losing himself – a very Air Nomad dilemma. By the end, Aang shows it’s possible to save the world and honor his Air Nomad ethos. In Korra’s time, the Air Nomads balance being helpers (engaged with the world) with not getting entangled in politics or power. They become something akin to the Jedi of the Avatar world (and indeed, the Jedi in Star Wars were themselves partly inspired by Shaolin and Buddhist monks!).

Finally, the Air Nomads teach viewers about cultural appreciation. Many kids watching Avatar may have had their first exposure to concepts like meditation, chakras, or the idea of vegetarian monks through Aang’s story. The show gently educates its audience that there are ways of life very different from the modern, materialist world – ways focused on inner peace, balance with nature, and kindness. Adults often pick up on the more nuanced references and can appreciate how respectfully Avatar handles these. The fact that a popular kids’ show managed to weave in Shaolin martial arts, Tibetan Buddhism, and Daoist wisdom into its fabric is part of why Avatar: The Last Airbender remains beloved by all ages. It presents these real-world philosophies in an accessible, exciting way, embodied by lovable characters and a gripping narrative.

Conclusion: The Air Nomads stand as a testament to how fiction can reflect reality. By looking at Shaolin monks, Daoist sages, and Buddhist ideals, the creators of Avatar gave us Airbenders who feel like genuine spiritual warriors – people who live lightly and freely, as the wind itself. Their legacy in the series is one of hope, compassion, and balance. In our world, they spark curiosity about Eastern philosophies and admiration for those who choose a life of peace. As Guru Laghima’s words remind us, sometimes letting go is the key to true freedom. The Air Nomads let go of what weighed them down – be it material attachments or hatred in their hearts – and in doing so, they gained the sky. Their story encourages each of us, child or adult, to find a bit of that Air Nomad spirit: be kind, be free, and always keep your inner wind flying.

Avatar: Bending Styles & Weapons

Interested to learn more about “Avatar: The Last Airbender”? Check out our article “The Exact Martial Arts Styles Behind Avatar: The Last Airbender Bending” to learn about the Chinese Martial Arts Styles, Weapons, and Philosophy within the show!