Fragmentation and Transformation (Three Kingdoms, Northern & Southern Dynasties)

Following the collapse of the Han Dynasty, China entered a long era of division and war—but also one of profound cultural growth. In Part 3 of The Dynasties That Shaped China, we examine the Three Kingdoms (Sānguó 三国) and the Northern and Southern Dynasties (Nánběicháo 南北朝), an age when emperors rose and fell in quick succession, yet poetry, religion, and philosophy flourished like never before. Amid the chaos of rival states, new faiths took root: Buddhism (Fójiào 佛教) expanded rapidly, supported by rulers and monks alike, while Daoism (Dàojiào 道教) grew into a spiritual force. It was in this era that the Shaolin Temple (Shàolínsì 少林寺) was founded—a sanctuary of faith and martial discipline that would come to symbolize the harmony between inner cultivation and outer strength. This was a time when China transformed not through unification, but through resilience, reinvention, and spiritual depth.

The Three Kingdoms (Sānguó 三国, 220–280 CE)

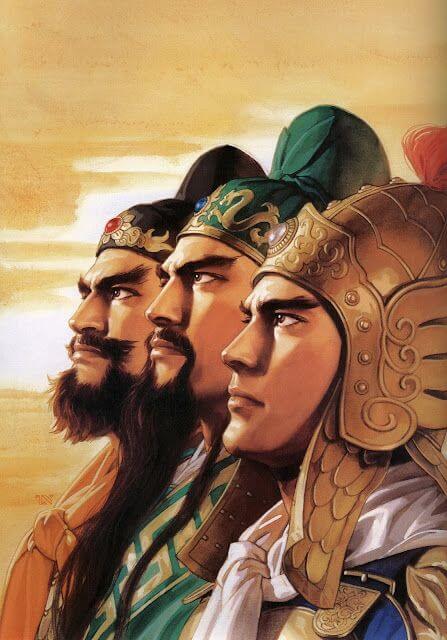

When the Han Dynasty fell, China splintered into warring regional regimes. The most famous of these – glorified in literature and popular imagination – is the Three Kingdoms period. This era, albeit short-lived (roughly 60 years from 220–280 CE), looms large in Chinese cultural memory thanks to the beloved historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms (which much later dramatized the events in epic detail). In reality, the Three Kingdoms were three rival states that claimed the mantle of Han: Cao Wei (魏) in the north, founded by Cao Pi (son of the formidable warlord Cao Cao); Shu Han (蜀) in the southwest, led by Liu Bei (a distant Han relative and folk hero); and Eastern Wu (吴) in the southeast, ruled by Sun Quan. These three powers engaged in a dynamic, shifting conflict for supremacy over China.

The age was characterized by near-constant warfare, intrigue, and shifting alliances – a true “Game of Thrones” of ancient China. Yet amid the turmoil, legends were born. Heroic figures such as Zhuge Liang, the astute chancellor of Shu known for his ingenious battle strategies, and Guan Yu, the oath-sworn brother of Liu Bei famed for his loyalty and martial prowess, became household names. Over time Guan Yu was even deified as Guān Dì (关帝), the God of War, worshipped by soldiers and later by martial artists as a patron of brotherhood and righteousness. The tales of brotherhood, such as Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei swearing an oath of loyalty in a peach garden, encapsulate the ideal of yì (义, loyalty and righteousness) that resonated in Chinese ethos. These stories – though romanticized later – all trace back to this chaotic era when valor and strategy were keys to survival.

Economically and socially, the prolonged conflict decimated populations in some regions and led to mass migrations. The north, under Cao Wei, retained a semblance of centralized bureaucracy and continued many Han institutions (Cao Cao, before the Three Kingdoms officially began, had already instituted agricultural colonies and recruitment of Xiongnu cavalry). The Shu and Wu states similarly tried to build effective governance in their territories, though on a smaller scale. Technological and scientific progress slowed under constant war, but there were still notable developments. The mechanical engineer Ma Jun of Cao Wei, for instance, invented a south-pointing chariot (an early compass vehicle) and an improved loom. Military technology also saw innovations like improved repeating crossbows and naval weaponry (Eastern Wu, occupying the Yangtze Delta, had a strong navy).

Culturally, the Three Kingdoms period’s greatest legacy was historical and literary. Statesmen like Chen Shou compiled histories (Records of the Three Kingdoms), preserving accounts of the time that later fed novelists’ imaginations. In the realm of philosophy, Neo-Daoism (Xuánxué 玄学) began to gain popularity among the educated class. Scholars disillusioned by war retreated into abstruse philosophical conversations (the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove are emblematic of this trend), blending Laozi, Zhuangzi, and Yi Jing ideas with a carefree, bohemian flair. These developments indicated a quest for meaning amid chaos – a theme that would recur in subsequent periods of disunity.

[Li Shida (1550–after 1623) – Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove]

Religion also evolved. Buddhism, which had trickled into China under late Han, began spreading more widely in the Three Kingdoms era, especially in the south. Monks from Central Asia arrived, and translations of sutras multiplied. The kingdom of Wei, for example, saw the first translation of the Lotus Sutra around esp. The turbulence and suffering of the age may have made Buddhism’s promise of salvation appealing. At the same time, Daoist mysticism took organized form – Wu Dou Mi Dao (Five Pecks of Rice sect) had led the earlier Yellow Turban revolt, and in the Three Kingdoms era, one Zhang Lu even ran a theocratic Daoist state in Hanzhong for a time (before submitting to Cao Cao). These spiritual currents set the stage for Buddhism and organized Daoism to flourish in the next period.

Although none of the Three Kingdoms succeeded in reuniting China by themselves, the period ended when the northern Wei kingdom (then under the Sima family, who had usurped Cao Wei and renamed it Jin) managed to conquer the other two in 280 CE, inaugurating the Western Jin Dynasty. The Three Kingdoms thus concluded with a brief reunification – but the Jin would soon crumble, leading to an even longer phase of division. Nevertheless, the Three Kingdoms era, with its tales of cunning strategists and loyal warriors, has captured East Asian imaginations for centuries. As the opening line of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms sagely puts it: “It is a general truth of the world that anything long divided will surely unite, and anything long united will surely divide.” The cycle of fragmentation and reunification is exemplified by this chapter of history.

Martial Heroes of the Three Kingdoms: Many Chinese martial arts schools and knightly brotherhoods later took inspiration from Three Kingdoms heroes. For example, Guan Yu, with his trademark long “Green Dragon” blade, came to embody loyalty and valor; martial artists worshipped him as a protector deity, and his image often adorns training halls. Zhang Fei, known for his fearsome strength, and Zhao Yun, famed for his bravery in battle (such as single-handedly rescuing Liu Bei’s infant son amidst an enemy army), became icons of courage. The brotherhood sworn by Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei was idolized as the perfect model of comradeship (jieyi 结义). Thus, the lore of the Three Kingdoms provided later generations with a treasure trove of values and symbols that transcended literature and filtered into the martial ethos.

The Northern and Southern Dynasties (Nánběicháo 南北朝, 420–589 CE)

China was briefly reunified under the Western Jin (280–316 CE), but that unity collapsed under internal strife and invasions by various non-Han (often called “Five Barbarians”) peoples from the north. What followed was a complex age of fragmentation known as the Northern and Southern Dynasties – a time of two parallel realms and profound transformation. Between 316 and 589 CE, North China was ruled by a succession of shorter-lived kingdoms (often founded by nomadic tribes who had migrated inside China’s borders), while South China was governed by Chinese-led dynasties that succeeded each other in Jiankang (modern Nanjing). This era is preceded by the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317–420) in the south, which was essentially a continuation of Jin for southern China after the north was lost, but by 420 Jin gave way to the first of the Southern Dynasties.

In the North, one pivotal kingdom was Northern Wei (北魏, 386–534), established by the Tuoba clan of the Xianbei people. Northern Wei managed to reunite much of North China by the late 5th century and undertook policies of sinicization – the Xianbei rulers adopted Han Chinese dress, surnames, and governance practices in an effort to stabilize their rule over a Chinese majority. The Northern Wei even moved their capital to Luoyang and aggressively promoted Chinese-style agriculture and administration. This policy had mixed success and later contributed to the state’s split, but it symbolizes the era’s ethnic fusion: nomadic and Han cultures intermingled, giving rise to a more diverse society. Various successor states followed Northern Wei in the north (Eastern Wei, Western Wei, then Northern Qi and Northern Zhou), each ruled by aristocracies of mixed heritage. Despite military conflicts, these northern regimes maintained a semblance of order and continued to use the machinery of a Confucian bureaucracy alongside their own tribal military structures.

Meanwhile, the South was ruled in succession by four dynasties – Liu Song, Southern Qi, Liang, and Chen – all founded by general-turned-emperors from the Eastern Jin’s Chinese ruling class. The Southern Dynasties kept Chinese traditions alive and are remembered for their courtly culture. The south, spared the worst of the nomadic invasions, became a refuge for northern gentry who fled across the Yangtze. These émigré elites brought with them classical learning and lifestyles, contributing to a southern florescence in letters and arts. For instance, the Southern Dynasties era witnessed refined poetry (the works of Tao Yuanming and Xie Lingyun), beautiful calligraphy (Wang Xizhi’s famed “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion,” written in 353 CE, is a high point of Chinese calligraphy), and advancements in painting (Gu Kaizhi, a Jin-era painter, laid foundations for figure painting). The south also saw significant technological progress, such as the mathematician Zu Chongzhi (5th century) calculating pi to seven decimal places and improving the calendar.

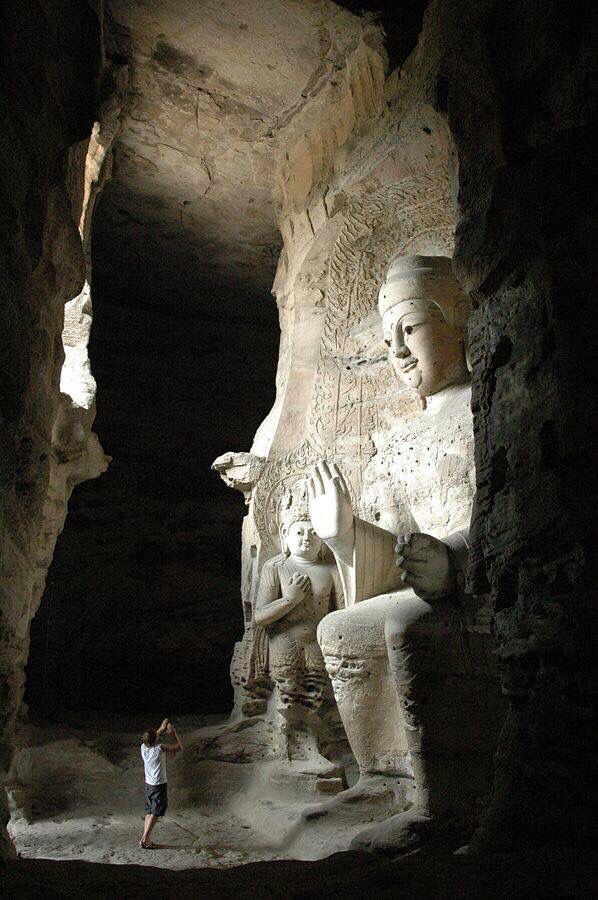

One of the most striking features of this period is the rise of Buddhism to prominence throughout China. The Northern and Southern Dynasties age was truly a Buddhist age in Chinese history. Northern rulers like the Northern Wei emperors converted to Buddhism and became lavish patrons of Buddhist art and infrastructure. They sponsored the carving of massive cave temple complexes – the most famous being the Yungang Grottoes in Datong and the Longmen Grottoes near Luoyang – featuring thousands of Buddha statues hewn into cliffs under imperial auspices. The image of the Buddha acquired distinctly Chinese features in these carvings, symbolizing how Buddhism was being sinicized. In the South, educated aristocrats also embraced Buddhism; Emperor Wu of Liang (r. 502–549) was so devout that he nearly became a monk himself, famously offering the throne to Buddha and “ransoming” it back with donations multiple times. Buddhist monasteries sprouted across the land, becoming important landowners and community centers. Translations of scriptures by foreign monks (like Kumārajīva in the late 4th century) and Chinese monks (like Xuanzhao) proliferated, and schools of Buddhist thought (such as Madhyamika and Yogācāra, known in Chinese as Sanlun and Faxiang) started to form. By late 6th century, Buddhism was deeply woven into Chinese society, among both elites and commoners – a remarkable transformation from its virtual absence in early Han times.

Daoism also evolved: organized Daoist religion (with rituals, scriptures, and priestly hierarchies) took shape in this era, partly in competition and partly in syncretism with Buddhism. The Celestial Masters sect continued in the south, and new Daoist texts like the Lingbao scriptures incorporated Buddhist-like concepts. Meanwhile, Confucianism, though out of official power due to the lack of a unified civil service, persisted as an ethical and family code among the populace and many officials.

Amid this rich cultural and spiritual landscape, everyday life was marked by division. The North and South developed somewhat separately for over 150 years, with limited interaction across the Yangtze barrier. The north had to integrate formerly nomadic peoples; the south had to build stability with fewer resources (as the economic heartland of China was traditionally the north). Each faced its own challenges: for instance, the Northern Zhou (the last northern dynasty before reunification) even briefly banned Buddhism and Daoism in 574 CE under Emperor Wu, trying to curb monastic power – a policy soon reversed by his successors.

In terms of martial developments, this period laid groundwork for later legends. Most notably, the Shaolin Temple was founded in the Northern Wei Dynasty. In 495 CE, Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei, himself a Buddhist convert, sponsored the establishment of a monastery at Shaoshi Mountain in Henan – what came to be known as the Shaolin Temple (少林寺). A Buddhist monk from India named Batuo (跋陀) became the first abbot. According to lore, some decades later Bodhidharma (Dámó 达摩) arrived at Shaolin (traditionally in 527 CE) and taught Chan (Zen) Buddhism and perhaps exercises to the monks. While many of the famous Shaolin martial arts myths (like Bodhidharma’s Yi Jin Jing muscle-changing classic or him training monks in boxing to keep them awake) are later embellishments, it’s during the Northern and Southern dynasties that the Shaolin Temple’s seeds in both spiritual practice and martial readiness were planted. The chaotic times required even Buddhist monks to know self-defense – there are accounts that Shaolin monks trained with staves to protect their monastery from bandits. This would flower into a full martial tradition in subsequent dynasties.

Thus, the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, though politically fragmented, was a crucible of cultural transformation. The notion of China as multi-ethnic took hold as Han Chinese and nomadic cultures fused in the north. Buddhism reshaped philosophy and art. The south preserved classical learning and advanced it in new directions. By the end of the 6th century, both regions were ripe for reunification – which came in 589 CE under the short but significant Sui Dynasty (not covered in this series, but Sui bridged into the Tang). The Sui reunification and its successor, the Tang, would build on the foundations laid in this time of division.

Origins of the Shaolin Monastery

The renowned Shaolin Temple – later famed as the cradle of Chinese kung fu – traces its origin to this era. In 495 CE, the Northern Wei emperor established Shaolin Temple on Song Mountain to honor an Indian monk, Batuo. The monastery gained renown for its scholarly translation of sutras. A few decades later, the semi-legendary Bodhidharma arrived. He is said to have meditated in a cave near Shaolin for nine years, and to have taught the monks a form of meditation that became Chan (Zen) Buddhism. Legends claim Shaolin monks practiced exercises (possibly an early form of qigong or martial drill) taught by Bodhidharma to strengthen body and mind. While historical records of Shaolin martial arts begin later (early Tang period), the image of Shaolin warrior-monks has its roots in these early days – a fusion of spiritual discipline and martial preparedness that uniquely symbolizes Chinese civilization’s blend of wen (culture) and wu (martial prowess).