Introduction

Imagine the pre-dawn light in a Shaolin Temple courtyard, where rows of grey-robed monks move in unison through a sequence of punches, kicks, and acrobatics. These synchronized routines, known as taolu (套路) or forms, are a cornerstone of Chinese martial arts training. Taolu are more than just flowing choreography – they are living textbooks of combat techniques and cultural wisdom handed down through generations. Yet, they often spark debate: some observers dismiss them as mere performance or “flowery” movements with little real fighting value. This article will explore what taolu truly are, why they evolved, and how they function across systems like Shaolin Kung Fu and other styles (Wudang, Hung Gar, Choy Li Fut, etc.). We’ll address common criticisms and misunderstandings and show that these forms, far from being impractical, were originally designed, and still used, as compact training methods to preserve and practice combat skills, coordination, energy work, and even philosophy.

What Are Taolu (Forms)?

In Chinese martial arts, taolu refers to a sequence of predetermined movements strung together into a continuous routine. Think of a taolu as a scripted fight against imaginary opponents: the practitioner performs offensive and defensive techniques in a set pattern. Traditionally, forms were teaching tools. They codified a style’s signature techniques, footwork, and strategies so that students could practice them solo and remember them. In fact, forms were originally intended to preserve the lineage of a style and were often taught only to advanced disciples entrusted with that knowledge. Each movement in a form often has an application in combat – a punch might represent striking to a vital area, while a low stance might train stability for grappling. Forms often include techniques that are not only direct representations of combat applications but also conceptual drills. These allow practitioners to extract, interpret, and pressure-test the movements through hands-on sparring and partner work. In essence, a taolu is a library of fighting techniques embedded in a dance-like routine.

Importantly, there are different types of taolu. The most common are solo forms performed by one person. But many traditional schools also have paired forms (dui lian 對練) – two-person choreographed fighting sets. These sparring forms let students practice timing and distance with a partner in a semi-controlled way. Whether solo or paired, forms were historically seen as training exercises rather than actual fights. They develop attributes needed for combat, such as balance, strength, speed, and muscle memory, in a consistent format. Over time, forms training develops the practitioner’s full physical range—improving flexibility, cultivating both internal energy and external strength, increasing speed and stamina, and reinforcing essential skills like coordination and balance. Students are often told to visualize an opponent while performing forms to keep their intent sharp – in other words, treat your form practice like real combat, so that the movements retain their martial meaning.

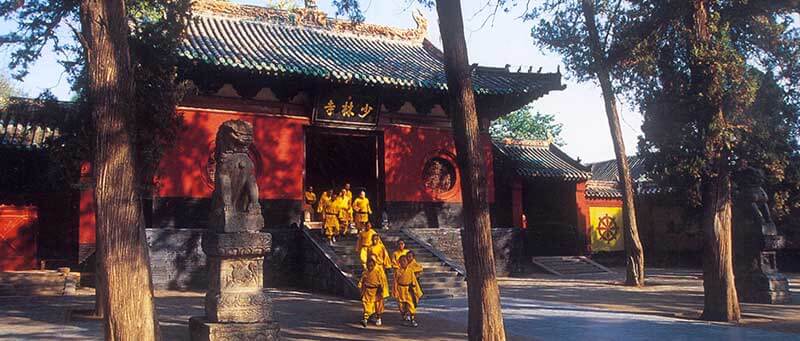

Origins and Historical Significance of Taolu in Shaolin

The Shaolin Temple, established over 1,500 years ago, is legendary for its role in developing and preserving martial arts. According to folklore, the Indian monk Bodhidharma taught exercises to the Shaolin monks to strengthen them for meditation; these exercises became the foundation of Shaolin Kung Fu. However, more official sources state that the earliest appearance of martial arts at the Shaolin Temple date back to the Northern Wei dynasty, specifically in the 19th year of the Taihe reign (495 AD). It was during this time that Emperor Xiaowen established the temple to house the Indian monk Batuo, roughly 30 years before Bodiharma would enter its halls. These sources state basic martial arts within the temple started in tandem with its founding.

Early Shaolin practice began with simple drills – one classic set is the Luohan Shiba Shou (18 Hands of the Arhat) said to be an initial set of 18 moves and 21 techniques. Over centuries, these drills evolved into dozens, then hundreds of forms as knowledge accumulated and different monks added innovations. Today, the Shaolin tradition is commonly said to include over 700 distinct taolu (forms). In fact, Shaolin Kung Fu became so rich in content that it’s considered the largest school of Chinese martial arts, giving rise to numerous sub-styles and routines.

Each Shaolin form often carried multiple purposes. On the surface, forms served as combat training drills – a way to practice strikes, kicks, and defenses solo. But they also doubled as conditioning exercises (strengthening legs through low stances, improving flexibility with high kicks, etc.) and as moving meditations integrating Chan (Zen) philosophy. Many forms are even named after philosophical or spiritual concepts (e.g. Xiao Luo Han Quan invokes the “Arhat,” a Buddhist enlightened being). This reflects how Shaolin viewed martial arts as part of a holistic practice for body, mind, and spirit. Historical records like General Qi Jiguang’s 16th-century military manual Ji Xiao Xin Shu documented Shaolin hand combat techniques and routines, indicating that by the Ming era, forms were well-developed training methods. Through turbulent times – war, rebellion, the rise and fall of dynasties – Shaolin forms preserved techniques that might otherwise be lost. They were a mnemonic device (a memory aid) as much as a physical exercise: a master could encode an entire fighting system in a single form, ensuring that even if books were burned or teachers perished, the movements themselves could carry on the art.

The cultural significance of taolu at Shaolin also cannot be overstated. Public demonstrations of forms helped spread Shaolin’s fame (for example, monks performing routines for emperors or, in modern times, for international audiences). Some forms were even used in religious rituals or festivals, blurring the line between combat and performance. As scholar Daniel Mroz describes, “Tàolù are acts of self-consecration that express martial theatricality and religiosity”, creating a “Martial Yoga of Space” where the practitioner’s movement has combative, theatrical, and spiritual dimensions. In other words, performing a form at Shaolin was at once a fighter’s drill, a monk’s moving meditation, and an actor’s expressive art. This rich blend of functions is part of why taolu remain central in Shaolin Kung Fu training to this day.

Taolu Across Different Chinese Martial Arts Styles

While Shaolin is a prime example, the use of forms is ubiquitous across Chinese martial arts. Nearly every style, whether classified as “external” (focused on physical power) or “internal” (focused on energy and mind), uses taolu as a training method. Throughout Chinese history it is said there have been hundreds, if not thousands differing styles and schools of martial arts, and many styles contain Taolu routines… meant to be practical and applicable, promoting agility, flow, meditation, flexibility, balance and coordination. Here are a few examples of how forms feature in various systems:

Wudang/Internal Styles: In the Wudang tradition (associated with Daoist arts vs Shaolin’s Buddhist focus), forms are slower and emphasize internal energy (qi) and breathing. Tai Chi Chuan (Taijiquan), for instance, is essentially one long taolu performed in slow motion to develop balance, softness, and internal power.

Bagua Zhang uses circular walking forms, and Xingyi Quan has linear drilling forms – all of these encapsulate their combat theories in set sequences. Wudang sword forms are also famous for their grace and depth. These forms carry philosophical teachings (Daoist concepts of yin-yang balance) and energy work (nei gong) within their movements. A Wudang form can look like a dance of flowing poses, but each is a martial application delivered with calm focus.

Hung Gar Kung Fu: This Southern style is known for its strong stances and powerful movements. Hung Gar’s curriculum revolves around several core forms. For example, Gung Ji Fook Fu Kuen (“Taming the Tiger”) is a long, foundational form teaching robust stances and basic techniques; Fu Hok Seung Ying Kuen (“Tiger Crane Double Shape”) combines the ferocity of the tiger with the elegance of the crane to train both external power and internal softness. The famous Tit Sin Kuen (“Iron Wire Fist”) form focuses on breathing, tension, and vocal vibration to develop internal energy (qi) and muscular endurance.

In Hung Gar, each form is a complete lesson: one may emphasize building raw strength, another developing agility, another training breath control. These forms are considered essential components of a practitioner’s training regimen, vital for cultivating the skills needed for effective self-defense. They also instill the style’s philosophy (e.g. the balance of hard and soft, symbolized by tiger and crane). Hung Gar practitioners typically spend years mastering a handful of forms, using them to refine body mechanics and mental discipline. As one description puts it, the forms “contribute to the development of skills and techniques necessary for effective self-defense while also promoting physical fitness and mental discipline”, making them indispensable for any serious student (source).

Choy Li Fut (Choy Lee Fut): Choy Li Fut is another large system, founded in the 19th century, that blends techniques from both northern and southern Chinese styles. It is renowned for having a vast number of forms – some branches have over 100 empty-hand and weapon forms. These include forms like Ping Kuen (Level Fist), Sup Ji Kau Da (Cross Pattern) and many weapon routines. Choy Li Fut forms are often long and vigorous, featuring rapid extended-arm strikes, circular blocks, and agile footwork. The forms drill the practitioner in generating power through torque and full-body movement, as well as chaining techniques in fluid combinations.

Because the system was designed to be comprehensive, its forms cover everything from close-range tactics to long-range kicks and weapons use. Different lineages of Choy Li Fut might emphasize different forms, but all treat taolu as a key training method to ingrain the style’s techniques and fighting strategies. Notably, Choy Li Fut’s effectiveness in bare-knuckle challenge fights during the late 19th–early 20th century was attributed to the realistic techniques embedded in its forms and the intense drilling of those movements. As some Choy Li Fut practitioners say, “Forms are the ways and not the ends” – meaning that the form is a method to practice and understand fighting principles, not an end in itself.

Wing Chun: This is a more streamlined southern art (famous for Bruce Lee’s early training). Wing Chun has only three hand forms, two weapon forms, and a wooden dummy form, which are much shorter and simpler than Shaolin forms, yet they encapsulate the system’s entire combat theory. For example, the first form Siu Nim Tao looks like a slow, stationary hand movement drill – it ingrains fundamental arm positions and energy. The fact that even a no-nonsense combat system like Wing Chun has forms underscores how central the concept is in Chinese martial arts: even when minimalistic, a form serves as the reference manual of the style. Each Wing Chun form is practiced to refine precision and the relaxed power Wing Chun is known for. Wing Chun’s approach shows that forms need not be acrobatic or lengthy to be valuable; even economical sequences provide a structure for solo training and internalizing reflexes.

From Northern Shaolin Long Fist forms that are acrobatic and extended, to Southern Praying Mantis forms that are short and filled with rapid angular strikes, taolu are a common thread. They provide a pedagogical framework – a way to package complex techniques and principles into learnable units. Many styles historically kept their forms closely guarded as secret knowledge, which again highlights their perceived importance. The consistency of forms across Chinese martial arts is why one source notes that “taolu or routine training is considered by many to be one of the most important practices in Chinese martial arts” (source). While each system’s forms have their unique flavor, they all serve the dual purpose of preserving tradition and training the body-mind of the practitioner.

Criticisms and Misunderstandings of Taolu

With the rise of modern combat sports and full-contact competitions, traditional forms training has come under scrutiny. A common criticism is that taolu are “unrealistic” – that practicing choreographed moves against an imaginary opponent doesn’t prepare one for the chaotic reality of a live opponent. Detractors often call forms impractical or merely aesthetic, sometimes sneeringly referring to them as “flowery fists and embroidery kicks.” Indeed, when watching a flashy contemporary wushu routine with flying spins and splits, a layperson might doubt its combat value. Even within the martial arts community, form-specific techniques have long been criticized as having no actual fighting utility. The sight of a kung fu stylist doing elaborate techniques that never appear in a kickboxing ring fuels the notion that forms are outdated.

It’s true that in modern sports wushu (the performance art developed in the PRC), the emphasis is on expression, difficulty, and aesthetic rather than direct combat application. Competitors in taolu events execute high jumps, rapid kicks, and poses for points, and their movements have been adapted for maximum visual appeal. On the other hand, sanda (Chinese full-contact kickboxing) bouts look very much like Muay Thai or kickboxing – straightforward punches, kicks, and throws with minimal flair. This contrast can make it seem as if there’s a complete disconnect between form and fighting. As one observer noted, “In taolu the techniques are very flowing and acrobatic… however in sanda it looks more like kickboxing with grappling” (source). Often, athletes specialize in either forms or fighting, further separating the two disciplines. This specialization was not always the case historically but is a reality of modern competitive wushu, and it reinforces the perception that forms are just a performance.

Another misunderstanding arises when practitioners expect forms and sparring to look the same. In arts like karate or taekwondo, as well as Chinese systems, beginners might think that the exact sequences in their forms should directly appear in a fight. When they don’t, they feel the form has “failed.” As one martial artist explains, people sometimes “misunderstand what forms are for… They think sparring and forms are both for fighting, and so they should look the same. They really just don’t know how to interpret them” (source). This lack of understanding leads to either practicing forms with no clue of their application (turning them into empty dance), or rejecting forms entirely as useless since they don’t mimic free sparring. The truth, as he notes, is that much of what’s in traditional forms is closer to self-defense scenarios or stand-up grappling – responses to grabs, holds, or sudden attacks – which aren’t apparent in kickboxing-style sparring. So if one only measures forms by how they compare to kickboxing, their value is missed.

There’s also historical criticism: even in early 20th-century China, some reformers of martial arts argued that too much emphasis on forms and display had diluted the real combat effectiveness. This led to movements to re-integrate sparring and drilling as primary training methods. Traditionalists, however, counter that forms were never supposed to replace sparring – they were one part of a larger training whole. In fact, traditionally, forms played a smaller role in training for combat application and took a back seat to sparring, drilling, and conditioning. This is a key point: even the old masters acknowledged you must practice applications with partners and test yourself in fights for the training to be complete. The problem comes when forms are practiced in isolation without that supplemental training – a scenario that unfortunately became common in some civilian schools or modern “performance-only” academies. Critics saw (and still see) those cases and conclude that forms training is to blame, rather than the incomplete training regimen.

Finally, the dramatic flair of some forms, especially those adapted for movies, can give an impression of fantasy. Cinematic fight choreography often is essentially customized taolu designed to wow audiences with improbable techniques (wire-assisted flips, etc.). Viewers might conflate those choreographies with the real traditional forms. It’s worth noting that many Hong Kong action stars like Jet Li and Donnie Yen came from competitive wushu forms backgrounds – Jet Li, for example, is a five-time national wushu champion known for his Changquan and weapon forms. They brought the beauty of taolu to the silver screen, which popularized kung fu worldwide but also led some to think of kung fu as only what they saw in movies. The entertainment adaptation of forms, while a testament to taolu’s visual impressiveness, sometimes further muddies their real purpose in training.

Why Taolu Matter: Practical Value and Deeper Benefits

Despite the criticisms, taolu endure because they serve unique and irreplaceable functions in martial arts training. First and foremost, they are a method to practice combat techniques in a structured way. In a well-designed form, every stance, step, strike, or block has a meaning. Traditional teachers often insist that “train your routine as if you were in combat and apply your skill as if it were a routine” (source) – highlighting that there is meant to be a one-to-one relationship between form and application. The form trains you to execute a movement with power, precision, and the correct body mechanics; application practice then takes that movement and adapts it to a live scenario. When done properly, forms and sparring feed into each other. Chinese martial arts have the concept of jing, qi, shen (essence, energy, spirit) – forms are said to train all three. Physically, they develop strength, flexibility, coordination, and balance. Internally, they teach breath control and concentration, building calm and focus under pressure. Mentally, they transmit the shen or spirit of the style – whether it’s the ferocity of Tiger style or the serenity of Tai Chi.

One clear practical benefit of forms is attribute development. For example, low horse stances held in forms build leg endurance and a strong root; high kicks in forms increase hip flexibility and agility; rapid sequences improve cardiovascular stamina. It’s no coincidence that traditional forms training often produces athletes with tremendous leg strength and athleticism. Practicing taolu over time systematically enhances a practitioner’s physical attributes—developing flexibility, strengthening both internal and external systems, building speed, and increasing overall endurance. In days before modern gyms, the form itself was a full-body workout. Shaolin forms in particular are famous for engaging every muscle group, requiring the practitioner to coordinate upper and lower body, left and right, in a unified way. As Shaolin master Shifu Yan Lei puts it, “Shaolin Forms teach the many muscle groups in our body to work together, building endurance, balance, and power. These ancient forms teach us how to move in our modern life… Everything becomes part of our training: total mind-body wellness.” In other words, beyond fighting, the act of practicing a form is healthful exercise and mindfulness combined.

Another vital aspect is technique preservation and depth. A form can pack in techniques that might be rare or situational, ensuring they aren’t forgotten. It can also encode tactics: for instance, a form might intentionally alternate between long-range and close-range moves, teaching the practitioner to flow between distances. Sequences of moves in forms often have an internal logic – they might depict a sequence of defense and counterattack. When students and teachers drill into the form’s movements (a practice known as applications research or bunkai/yongfa), they uncover a wealth of combat knowledge. If you pluck techniques out in isolation or perform forms mindlessly, you miss that context. But if studied, forms can teach complex defensive scenarios: how to escape a choke, how to trip an opponent after blocking, etc., all hidden in plain sight. Forms are like coded text – to the untrained eye they’re gibberish, but to the initiated they convey important instructions.

Taolu also instill muscle memory and reflexes. By repeating a form hundreds of times, certain movements become ingrained to the point that, under stress, your body can execute parts of them automatically. For example, many forms teach the practitioner to return to a ready stance or guard position after each combo – a habit critical in actual fighting. They also train the transitions between techniques, which is often where real fights are won (flowing from a block into a strike, etc.). In essence, forms practice is like shadow boxing with a clear script to ensure you cover all bases. A boxer might hit the heavy bag and drill combinations; a kung fu practitioner performs a form to drill combinations and body method. Neither alone is sufficient, but each reinforces the other.

Beyond the combative and physical, taolu carry cultural and philosophical teachings. Each style’s forms often reflect its guiding principles or the philosophy of its creators. For instance, the Five Animals forms (Tiger, Crane, Leopard, Snake, Dragon) found in certain southern styles are not just about mimicking animals – they impart the concept of adapting to situations with different strategies (strength of Tiger, evasiveness of Snake, etc.) and balancing yin and yang energies. Some forms tell a story or commemorate an event. Many have poetic names that encode lessons (e.g., a form named “Plum Blossom Fist” might emphasize footwork patterns like the five petals of a plum flower, teaching the practitioner to move in five directions). In practicing such a form, students unconsciously absorb those ideas. Performing a form can be a way of connecting with history and culture – doing the same movements that monks or warriors did hundreds of years ago, and in so doing, meditating on the principles they embodied.

Finally, taolu have value as a discipline and patience builder. Mastering a complex form can take months or years. It demands mental focus, memory, and perseverance. This process itself is character-building. It teaches the student how to break down a big task into smaller sections, how to pay attention to detail (a bent knee here, an extended finger there), and how to remain calm and present in the moment (because losing focus in mid-form means you forget the sequence). Many instructors say that forms practice can be a form of moving meditation – you must synchronize your breathing with movement, clear your mind, and be fully engaged. This aspect links to the idea of energy work (Qi Gong) within forms: coordinating breath with motion helps cultivate internal energy and can have stress-reduction benefits. Indeed, practitioners often report entering a “flow state” during a well-practiced form, feeling a unity of mind and body. In the Shaolin tradition, these exercises are considered a pathway to Zen (Chan) insight, where breath serves as the vital connection between body and mind. Because taolu demand full mental presence and synchronized breathing, they naturally foster mindfulness—making it nearly impossible to perform them without focus or awareness. Thus, taolu can serve a spiritual purpose too, aligning the practitioner’s mind, breath, and movement – a triad at the heart of many Eastern disciplines.

Evolution of Taolu in Modern Contexts

Taolu have continually adapted to serve the needs of their time. In the 20th century, as China sought to promote its martial heritage, traditional taolu were compiled and sometimes standardized. For example, the Chinese government created standardized versions of certain forms (like Simplified 24-form Taijiquan or standardized Changquan longfist routines) for ease of teaching and competition. This helped spread martial arts but also subtly shifted focus from combat efficacy to performance and health in many cases. The modern sports wushu divides into two distinct components: taolu (forms competition) and sanda (full-contact fighting). High-level taolu competitors today train much like gymnasts or dancers, aiming for explosiveness, flexibility, and grace. They incorporate dazzling acrobatics that, while rooted in martial movements, are pushed to extremes for scoring purposes. The International Wushu Federation (IWuF) routines even include “Nandu” (difficulty moves) such as aerial kicks and twists that must meet criteria for points. This sportification has made taolu competitions exciting to watch and has kept the practice of forms very much alive among youth. However, it also means that in some circles, forms are practiced primarily for show, with combat application being secondary. But, the dedication and skill of of sports wushu should not be undervalued:

Excerpt from “Is Modern Kung Fu ‘Real’ Kung Fu?”

Yes, modern kung fu is real kung fu—but kung fu might not be what you think it is. The term ‘gong fu’ (pronounced ‘kung fu’ in the West) can be used in many fields as an achievement of perseverance, skill, and excellence within a field. It is a description of the level of a practitioner...

So, if kung fu is a descriptive word for many things, what then, you may ask, are martial arts called in China? The answer: wushu. Wushu is the literal translation for martial arts and, despite the word’s association… with ‘modern’ martial arts, it has been around for millennia…

When asked about ‘modern’ wushu, Master Bao’s [Buddhist name Shi Xing Jian, a 32nd-generation Shaolin warrior monk] response was clear: it is excellent practice, and in some ways, it can be even more challenging than traditional wushu. The reason is that modern wushu incorporates visually striking elements—deeper stances, faster movements, and higher jumps—that demand greater physical agility, muscle power, and flexibility. These exaggerated movements, while sometimes criticized for their focus on aesthetic beauty, actually help practitioners build essential martial skills… If a student can perform these complex movements fluidly and swiftly, transitioning to traditional stances and techniques becomes more accessible and efficient... Many martial artists who first train in modern wushu tend to excel when they later take up traditional styles.

On the other hand, traditional kung fu schools around the world still use forms in their original spirit – as one part of a complete training that includes basics, forms, drilling applications, sparring, and conditioning. In fact, there’s a growing movement among some martial artists to “prove the contrary” to the critics by demonstrating that “Wushu taolu techniques CAN and HAVE been applied via sparring”. They showcase examples of techniques lifted straight from forms being used successfully in sanda or other sparring formats. This kind of work helps bridge the gap between traditional and modern training, reinforcing that forms are not obsolete at all. For instance, some sanda fighters cross-train in traditional styles to learn unconventional techniques (a sweep or spinning backfist from a form might catch an opponent by surprise if mastered). The late Grandmaster Ma Xianda, who was both a traditionalist and a sanda coach, famously advocated testing one’s traditional skills in fighting arenas: “If you say you have some secret technique, you should examine it scientifically and find out how it works… What is the experimental lab of Wushu? That is the tournament or the battlefield.” His words underline that forms techniques need proving grounds – and when given such, their value becomes evident.

Taolu have also evolved in media and pop culture. In Chinese opera and folklore storytelling, martial forms were used to dramatize heroic feats. Today, kung fu films and even video games carry that torch. The beauty and variety of taolu have made them a global cultural treasure – people may not know the applications of what Jet Li is doing on screen, but they are enthralled by the spectacle. This widespread exposure has ironically led many to seek out traditional schools to learn “the real thing” behind the movie moves, often discovering the depth of forms in the process. Moreover, outside of China, tournament circuits for traditional forms (separate from modern sports wushu) allow practitioners of styles like Hung Gar, Wing Chun, etc., to perform their classical forms competitively. These events prioritize authentic expression of the style over pure acrobatics, thus encouraging martial artists to keep the old forms alive and well-practiced.

Even in contemporary self-defense discourse, elements of forms training are appreciated. The concept of ingraining responses through repetition is analogous to drills in Krav Maga or MMA. Some techniques preserved in forms (joint locks, for example) are finding use in law enforcement or personal defense when adapted appropriately. Thus, while one might not use an entire choreographed sequence in a fight, chunks of forms translate into practical combinations. The key is the practitioner’s understanding. As a kung fu adage goes, “It’s not the form that’s ineffective; it’s the interpretation and training method.” When trained with intent, forms become a powerful tool in a fighter’s toolbox, building attributes and cataloging techniques that can be pulled out when needed.

Conclusion

Taolu have been aptly described as the “soul” of Chinese martial arts, preserving not only the techniques but the essence of each style. Far from being mere flowery display, a form is a multifaceted training method: part technique encyclopedia, part calisthenic workout, part moving meditation, and part historical artifact. The example of Shaolin Kung Fu – with its hundreds of forms developed over 1,500 years – shows how integral forms were in creating a complete martial artist capable of self-defense, spiritual cultivation, and artistic performance. Other systems, from the internal arts of Wudang to the fierce strikes of Hung Gar and the rapid-fire combinations of Choy Li Fut, all use taolu to teach and test their practitioners.

Yes, to the uninitiated, forms can look impractical, and indeed if one only practices forms without applying their lessons, they can become empty movements. But when understood, taolu are revealed as a genius method of simulation – a way to fight multiple opponents in one’s imagination, to repeat sequences until they are second nature, and to challenge the body in ways live sparring may not always do safely (for instance, practicing high-risk throws or weapons techniques solo first). The criticisms of taolu often stem from misuse or lack of context. When placed back into the full context of traditional training – where forms, sparring, drills, and theory all interlock – taolu emerge as incredibly practical and efficient. They allow a lone practitioner to continue honing skills when no partner is available. They allow an art to be passed down in entirety even if only parts can be used at a time. And they keep alive the artistic beauty and cultural richness of kung fu, which is a heritage as much as a combative discipline.

In modern times, taolu have proven adaptable: they shine on the competition floor and silver screen, but still retain their old value in the training hall and sparring ring when properly harnessed. A well-rounded martial artist can appreciate both the aesthetic grace of forms and the effective techniques hidden within them. Rather than “impractical dances,” forms are more like shadow-boxing with a classical syllabus, a way to sharpen one’s sword when real duels are scarce. It’s telling that millions worldwide continue to practice traditional forms every day – if they were pointless, they would have been abandoned long ago. Instead, they persist, a testament to their efficacy at training body and mind. In the ecosystem of Chinese martial arts, taolu are the preservers of knowledge and the drills of mastery. They connect past to present, teacher to student, theory to action. From the Shaolin monk in meditation to the tournament champion on the lei tai platform, all attest in their own way to the enduring importance of taolu in keeping the fighting arts of China alive, dynamic, and profound.