Warrior Nuns in the Sacred Mountains

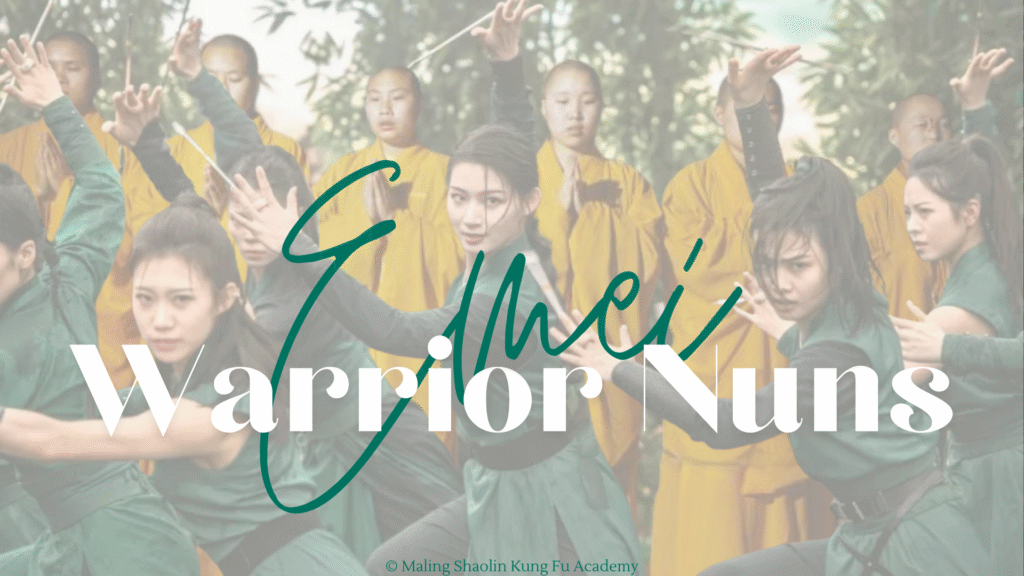

High in the misty heights of Mount Emei – one of China’s four sacred Buddhist mountains – a community of Buddhist nuns carries on an ancient martial tradition. Known as “Emei warrior nuns,” these women integrate rigorous Emei-style Kung Fu training with a devout monastic lifestyle. Their days are a balancing act of meditation, prayer, and physical discipline. In the early predawn hours, the nuns wake for chanting sutras and meditation. Then, as sunlight filters through the forests of Emei, they exchange rosaries for wooden staves and training swords, beginning hours of martial arts practice.

Much like their male counterparts – the famed Shaolin warrior monks – Emei’s nuns view kung fu as both a means of self-defense and a moving meditation. Their martial practice is imbued with Zen Buddhist principles: cultivating mindfulness, discipline, and compassion. The nuns’ training reinforces their meditation practice – strengthening body and mind so they can sit in stillness for hours. In essence, kung fu becomes a path to enlightenment: a discipline that tempers the body, cultivates inner calm, and expresses Buddhist values in action.

Training in Emei-Style Kung Fu and Monastic Life

Within the tranquil nunneries of Mount Emei – such as the historic Fuhu Temple – the daily routine is demanding. After morning prayers and a vegetarian breakfast, the warrior nuns dedicate themselves to Emei-style kung fu training. Emei kung fu is renowned as one of China’s great martial arts traditions, emphasizing agility, fluidity, and a balance of soft and hard techniques. It is often characterized as softer than Shaolin’s explosive power yet harder than Wudang’s purely internal styles.

The nuns practice low stances and quick, light footwork inspired by animal movements. They drill fist forms and weapon routines, including swords, staffs, and the distinctive Emei piercers – two small metal blades worn on the middle fingers that evolved from ornamental hairpins. These piercers are spun in elegant arcs, embodying feminine grace with martial precision.

Training is rigorous. A daily regimen may start with two hours of physical conditioning at dawn, followed by instruction in specific routines and weapons practice. This training is not merely athletic; it becomes moving meditation. Each movement is delivered with focused intention and mindful breathing. Repetition of forms sharpens attention, and kung fu instills vitality and focus that carries into spiritual duties.

Daily life also includes temple chores – sweeping courtyards, tending gardens, cooking meals – all considered mindfulness practices. Evening activities include chanting, prayer, and silent meditation. The nuns view physical hardship as tests of resolve on the Buddhist path. They exemplify the ideal of “Chan Wu He Yi” – the unity of Zen and martial arts – living as both contemplatives and fighters.

Blending Martial Practice with Spiritual Discipline

Mount Emei has long been a crossroads of religious and martial traditions. Unlike the Shaolin Temple (purely Buddhist) or Wudang Mountain (Daoist), Mount Emei absorbed Buddhist, Daoist, and Confucian influences. Historical records describe monks and recluses practicing martial arts for health, self-defense, and spiritual refinement. Emei martial arts evolved into a vast system with over 1,000 bare-hand forms and hundreds of weapon routines.

Some masters, such as the Baiyun Zen master during the Southern Song dynasty, merged Zen insights with martial training. This legacy lives on in the warrior nuns’ practice, which harmonizes action with meditation. Emei’s philosophy emphasizes using skill to overcome brute force, yielding and redirecting power. These principles align with Buddhist teachings of restraint and wisdom. Emei fighters learn evasive footwork and efficient strikes aimed at subduing rather than harming.

Weapon forms carry spiritual symbolism. The Emei piercers require ambidextrous precision, reflecting balance and harmony. Sparring includes bows of respect, embodying martial ethics (wude) of humility and compassion. The training hall becomes both dojo (wǔ guǎn) and sacred space, and through physical training and meditation, the warrior nuns cultivate both martial skill and enlightened character.

A Living Tradition and Its Historical Roots

The idea of warrior nuns on Mount Emei bridges both history and legend. In Chinese popular culture, the Emei Sect has been portrayed as an order of sword-wielding nuns, popularized by Jin Yong’s wuxia novels. Though fictional, these tales were inspired by Emei’s historical openness to female practitioners.

Emei’s martial arts were historically egalitarian. Its techniques, favoring agility over brute strength, were accessible to women. Local lore speaks of female swordsmasters and “nu xia” (female knights-errant), though official histories rarely record their names. The legendary Shaolin nun Ng Mui, credited with founding Wing Chun, is sometimes linked to Emei, symbolizing women’s contributions to martial arts. Her story, and those of her disciples, reflects a tradition of female martial innovation.

Other female-centric martial communities include Shaolin’s Yongtai Monastery, known for warrior nuns since the 6th century. Even today, Yongtai hosts an all-female wushu school where nuns train in Shaolin kung fu. The Drukpa nuns in the Himalayas have similarly gained fame for integrating Chinese martial arts into their Buddhist practice. These examples confirm that the warrior nun is a living reality in Asian martial culture.

Emei’s Warrior Nuns in Contemporary Society

Today, Emei’s warrior nuns help preserve an intangible cultural heritage. Emei Wushu was officially recognized as a National Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2008, leading to new support for training facilities and festivals. Visitors may witness temple demonstrations where nuns and monks perform traditional forms.

One group that brought visibility to Emei martial arts is the Emei Kung Fu Girls, an all-female troupe showcasing Emei-style routines in viral videos and live performances. Though not monastics, their visibility has sparked renewed interest in Emei’s female martial legacy. Chinese state media and officials have praised them as modern heroines. Some nuns have welcomed the publicity, though their focus remains spiritual. Others teach martial arts to local girls, promoting empowerment and self-defense.

Outside recognition has brought funding and allowed for lay instructors to exchange knowledge. International enthusiasts now visit Emei to train, often finding elderly nuns who spar with agility and skill well into old age. Their continued practice reinforces the mystique and legacy of Emei’s warrior nuns.

Emei’s Warrior Nuns vs. Shaolin’s Warrior Monks

Shaolin warrior monks and Emei warrior nuns represent complementary Buddhist martial traditions:

- Monastic Structure: Shaolin Temple is male-only; women train at separate temples like Yongtai. Emei includes monks and nuns within a network of temples, and its martial tradition has historically been open to women.

- Martial Style: Shaolin kung fu emphasizes power and direct force. Emei focuses on agility, finesse, and blending hard and soft techniques. In general, Shaolin weapons include staffs and broadswords; Emei includes piercers and straight swords requiring dexterity – but many weapons can be found in both traditions.

- Philosophy: Both follow Chan Buddhism. Shaolin emphasizes meditation and martial drilling; Emei integrates Daoist energy work and Confucian ethics. Both aim for mastery of body and mind, self-improvement, and service.

- Public Profile: Shaolin monks are globally famous. Emei’s warrior nuns are gaining attention through social media and state recognition. While Shaolin tours internationally, Emei’s tradition is mostly preserved locally but is increasingly respected.

Together, Shaolin and Emei represent the yin and yang of Chinese martial spirituality: one forceful and iconic, the other graceful and enduring.

Conclusion: Guardians of a Living Legacy

The warrior nuns of Mount Emei embody a rare synthesis of tradition and resilience. Living lives of simplicity, discipline, and compassion, they train in ancient techniques not for fame, but as part of a spiritual path. They uphold the legacy of Emei kung fu, demonstrating that martial skill and inner cultivation are not only compatible, but mutually reinforcing.

In today’s world, where distractions abound and cultural traditions face erosion, the sight of a nun calmly practicing sword forms beneath misty cedars speaks volumes. It is a testament to the enduring power of focus, grace, and devotion. The warrior nuns of Mount Emei do not seek the spotlight, but they shine nevertheless, as quiet guardians of a living, breathing heritage.