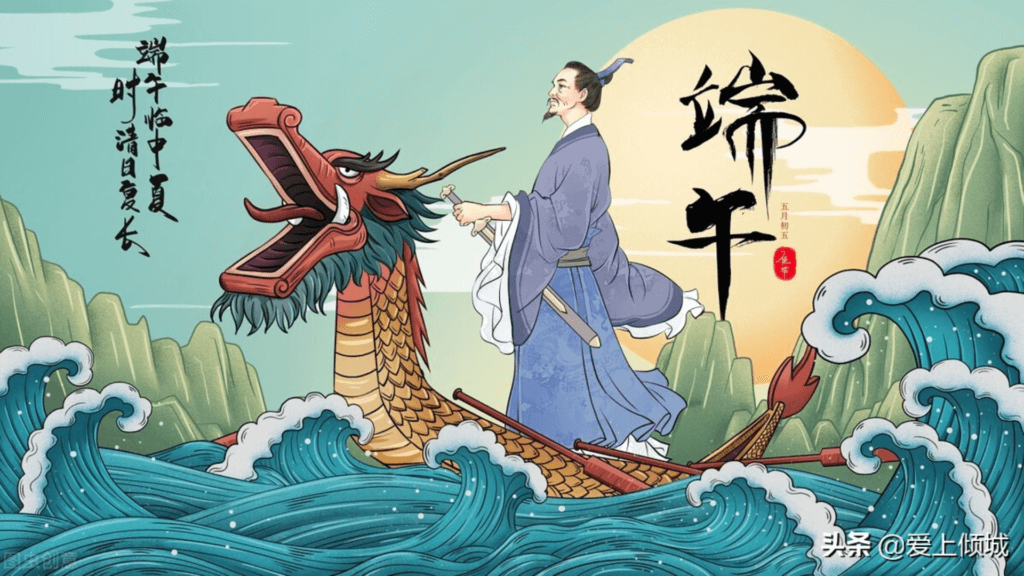

The Dragon Boat Festival, known as Duanwu Festival (端午节) in Chinese, is a traditional holiday celebrated on the fifth day of the fifth month of the lunar calendar. This festival, rich in cultural heritage and history, is observed with a variety of customs and activities that reflect China’s deep-rooted traditions and community spirit. The festival commemorates the life and death of the famous Chinese scholar Qu Yuan and is marked by dragon boat races, the eating of zongzi (rice dumplings), and other festivities.

Historical Significance

The origins of the Dragon Boat Festival date back over 2,000 years to the Warring States period (475-221 BC). It is widely believed to commemorate Qu Yuan (c. 340–278 BC), a loyal minister and poet of the State of Chu. Qu Yuan was known for his patriotism and contributions to Chinese literature. However, he fell out of favor with the king and was exiled. In despair over the corruption and political strife in his country, Qu Yuan committed suicide by drowning himself in the Miluo River.

According to legend, the local people, who admired Qu Yuan, rushed out in their boats to save him or retrieve his body. They beat drums to scare away fish and threw rice into the water to distract sea creatures from eating Qu Yuan’s body. This act of remembrance evolved into the dragon boat races and the custom of eating zongzi during the festival.

The Story of Qu Yuan: A Tale of Patriotism and Tragedy

To read the full tale, click this drop down

Qu Yuan (c. 340–278 BC) is one of the most revered figures in Chinese history and literature, known for his unwavering patriotism, profound literary contributions, and tragic end. His life and legacy are inextricably linked to the Dragon Boat Festival, which commemorates his devotion and ultimate sacrifice for his country.

Early Life and Career

Qu Yuan was born into a noble family in the state of Chu during the Warring States period (475–221 BC), a time characterized by intense political rivalry and warfare among several Chinese states. He was well-educated and demonstrated exceptional talent in literature and governance from a young age. His abilities and dedication earned him a prominent position as a minister and trusted advisor to King Huai of Chu.

Political Turmoil and Exile

As a statesman, Qu Yuan was committed to strengthening the state of Chu and advocated for reforms to enhance its political and military strength. However, his progressive ideas and outspoken nature made him many enemies in the royal court, especially among corrupt officials who saw him as a threat to their power.

These officials conspired to slander Qu Yuan, turning King Huai against him. Despite his loyalty and valuable counsel, Qu Yuan was accused of treason and subsequently exiled from the capital. During his years of exile, he traveled extensively, witnessing the suffering of his fellow countrymen and the decline of the state he loved.

Literary Contributions

While in exile, Qu Yuan wrote some of his most famous works, expressing his deep sorrow, frustration, and unwavering patriotism. His poetry, characterized by its rich imagery, emotional depth, and profound philosophical reflections, has left an enduring mark on Chinese literature. His most notable works include the “Li Sao” (离骚, “The Lament”), “Tian Wen” (天问, “Questions to Heaven”), and “Jiu Ge” (九歌, “Nine Songs”).

“Li Sao,” his magnum opus, is an autobiographical poem that conveys his sense of loss and despair over his unjust treatment and the fate of his beloved Chu. The poem is celebrated for its innovative use of language and metaphor, and it remains a cornerstone of classical Chinese literature.

The Ultimate Sacrifice

As the state of Chu continued to weaken, Qu Yuan’s despair deepened. When he learned of the fall of the Chu capital to the rival state of Qin, he was overwhelmed with grief and hopelessness. In a final act of protest and devotion, Qu Yuan committed suicide by drowning himself in the Miluo River on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month in 278 BC.

According to legend, the local people, who admired Qu Yuan’s loyalty and were anguished by his death, raced out in their boats to search for his body. They beat drums and splashed the water with their paddles to scare away fish and evil spirits. To prevent the fish from eating his body, they threw rice into the river. These acts of remembrance and mourning evolved into the customs observed during the Dragon Boat Festival, such as dragon boat racing and eating zongzi (rice dumplings).

Legacy and Cultural Impact

Qu Yuan’s life and work have had a profound and lasting impact on Chinese culture and literature. He is often regarded as China’s first great poet and a symbol of integrity and patriotism. His poetry continues to be studied and celebrated for its artistic merit and emotional power.

The Dragon Boat Festival, which commemorates Qu Yuan’s sacrifice, serves as a reminder of his enduring legacy and the values he championed. The festival’s traditions, from the thrilling dragon boat races to the preparation and consumption of zongzi, reflect the community’s collective memory and reverence for this remarkable figure.

In contemporary times, Qu Yuan’s story resonates as a testament to the importance of loyalty, courage, and the enduring power of the written word. His life and work continue to inspire generations, reinforcing the significance of cultural heritage and the timeless nature of human emotions and ideals.

Traditions

Dragon Boat Races

Dragon boat racing is the most iconic activity of the Dragon Boat Festival. These races are not only competitive sports but also deeply symbolic. The boats, usually decorated to resemble dragons, are long and narrow, accommodating teams of paddlers, drummers, and a steersperson. The races symbolize the villagers’ attempt to save Qu Yuan and have become a vibrant display of teamwork and cultural pride.

The races are accompanied by the beating of drums, which sets the rhythm for the paddlers and adds to the festive atmosphere. The dragon boats themselves are often elaborately decorated with dragon heads and tails, and their vibrant colors enhance the visual spectacle of the event.

Zongzi: The Traditional Delicacy

Eating zongzi, pyramid-shaped glutinous rice dumplings wrapped in bamboo leaves, is another essential part of the Dragon Boat Festival. Zongzi comes in various flavors and fillings, depending on the region. Common fillings include sweet red bean paste, dates, chestnuts, as well as savory fillings like marinated pork, salted egg yolk, and mushrooms.

The practice of making and eating zongzi is linked to the legend of Qu Yuan. It is said that the local people threw rice into the river to distract fish from his body, and over time, this ritual evolved into the tradition of making zongzi. Today, families and communities gather to prepare and enjoy zongzi together, celebrating unity and tradition.

Other Festive Traditions

In addition to dragon boat races and eating zongzi, several other customs and traditions are observed during the Dragon Boat Festival:

- Hanging Mugwort and Calamus: People hang bundles of mugwort and calamus (a type of reed) on their doors to ward off evil spirits and diseases. These plants are believed to have protective and medicinal properties.

- Wearing Perfumed Sachets: Children often wear colorful sachets filled with fragrant herbs and spices. These sachets are believed to protect them from evil and bring good luck.

- Drinking Realgar Wine: In some regions, people drink realgar wine, a type of Chinese liquor believed to repel insects and ward off evil spirits. It is also said to have medicinal properties.

- Balancing Egg: A less widespread but intriguing tradition involves trying to balance eggs at noon. Successfully balancing an egg is believed to bring good luck for the year.

- Performing Dragon Dances: In some areas, dragon and lion dances are performed to celebrate the festival. These performances are vibrant displays of cultural heritage and community spirit.

Contemporary Celebrations and Cultural Significance

The Dragon Boat Festival has evolved over time, blending ancient customs with contemporary practices. It is celebrated not only in China but also in various countries with significant Chinese communities, such as Malaysia, Singapore, and Taiwan. The festival has also gained international recognition, with dragon boat races held in many countries around the world.

In 2009, the Dragon Boat Festival was inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This recognition highlights the festival’s cultural significance and the need to preserve its traditions.

The Dragon Boat Festival serves as a reminder of the importance of cultural heritage, community, and collective memory. It brings people together to honor the past, celebrate the present, and look forward to the future. Whether through the thrill of dragon boat racing, the taste of zongzi, or the various other customs, the festival continues to be a vibrant and cherished part of Chinese cultural life.

Conclusion

The Dragon Boat Festival is a multifaceted celebration that encapsulates the rich tapestry of Chinese culture and history. Through its various customs and activities, it honors the memory of Qu Yuan, promotes community spirit, and preserves ancient traditions. As the festival continues to evolve, it remains a vital part of China’s cultural heritage, celebrated with enthusiasm and reverence both within China and around the world.