China is home to 56 officially recognized ethnic groups – one majority (Han) and 55 minority groups. The Han people form roughly 92% of China’s 1.4 billion population, leaving a rich variety of minority cultures comprising the remaining 8%. These minorities range from the Tibetans and Mongols of the high plateaus and grasslands, to the Yi of southwest China’s mountains, the Kazakhs of the far northwest steppes, the Miao, Hui, Manchu, Zhuang, Uyghur, and many more.

Throughout history, several of these groups rose to prominence as warrior peoples: the Mongols established the Yuan Dynasty in the 13th century, the Manchu (descended from Jurchen) founded the Qing Dynasty in the 17th century, and others like the Tibetans and various nomadic tribes were renowned for their martial traditions. Today, that warrior heritage is finding new life in the world of mixed martial arts (MMA).

In recent years, fighters from China’s ethnic minority communities – both men and women – have been making waves in professional promotions like the UFC and ONE Championship, as well as dominating regional circuits. They are not only winning bouts, but also bringing their unique cultural backgrounds into the spotlight, enriching Chinese MMA with diversity and pride.

This article explores the cultural context behind these fighters’ success, profiles some standout athletes (including Chinese citizens and ethnically Chinese fighters abroad), and examines how local traditions and regional MMA growth are fueling this phenomenon.

The Ethnic Mosaic of China

With 55 minority groups officially recognized in addition to the Han majority, China’s ethnic landscape is extremely diverse. The minority populations range from larger groups like the Zhuang (primarily in Guangxi), Uyghur (Xinjiang), Hui (Chinese Muslims), Manchu (northeast), Miao (southwest), and Yi (southwest), each numbering in the millions, to very small communities in the thousands. The Yi people, for example, number around 9 million – a small fraction of China’s population, yet lately they have “been punching (and kicking) far above their weight in the pugilistic arts” time.com.

Historically, many of these groups developed distinct martial customs due to the environments they lived in and the conflicts they faced. The Mongols* of the steppe honed wrestling and horseback archery as part of their Naadam “Three Manly Games” festivals. The Tibetans, living on the Roof of the World, developed their own styles of wrestling and horseback riding combat games. The Yi (also called Nuosu) of Sichuan’s Liangshan mountains had a reputation as fierce warriors – even clashing with Chinese imperial armies during the Long March era.

Other groups like the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and Mongolians* carried on nomadic warrior traditions, while communities like the Miao and Yao had hill-fighting tactics and the Hui drew upon Islamic wrestling and boxing influences. This cultural mosaic meant that, while the Han majority embraced striking arts like Shaolin kung fu and kickboxing, many minority regions retained strong grappling and wrestling practices.

In the modern era, the Chinese government has at times highlighted minority athletes in sports as a symbol of national unity in diversity (while also carefully avoiding political sensitivities). Ethnic minority athletes have shone in Olympic sports for China – e.g. Tibetan and Uyghur long-distance runners, a Hui weightlifting champion, etc.

Notable Olympic Chinese Ethnic Minority Athletes

Tibetan Athletes:

- Qieyang Shijie (Choeyang Kyi): Born on November 11, 1990, in a Tibetan herder’s family in Amdo province, Tibet, Qieyang Shijie made history by becoming the first Tibetan athlete to win an Olympic medal. She secured a bronze in the women’s 20km race walk at the 2012 London Olympics. In March 2022, following the disqualification of other athletes for doping violations, her medal was upgraded to gold, making her China’s first Olympic gold medalist from the Tibetan ethnic minority group. She has since competed in multiple Olympic Games, including the 2024 Paris Olympics.

- Duo Bujie: A long-distance runner of Tibetan ethnicity, Duo Bujie has represented China in various international competitions. He competed in the men’s marathon at the 2019 World Athletics Championships held in Doha, Qatar.

Uyghur Athletes:

- Dinigeer Yilamujiang (Dilnigar Ilhamjan): Born on May 3, 2001, in Altay, Xinjiang, Dinigeer Yilamujiang is a cross-country skier of Uyghur ethnicity. She made her Olympic debut at the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, where she was honored as one of the final torchbearers during the opening ceremony. She is also noted as the first Chinese cross-country skier to win a medal in an International Ski Federation (FIS) event.

Hui Athletes:

- Liao Hui: A distinguished weightlifter of Hui ethnicity, Liao Hui was born on October 5, 1987, in Xiantao, Hubei. He clinched the gold medal in the men’s 69kg weightlifting category at the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Throughout his career, Liao set multiple world records, including a 166kg snatch at the 2014 World Weightlifting Championships. However, it’s important to note that he faced a suspension in 2011 due to doping violations.

Now in combat sports, the same dynamic is unfolding. The rise of MMA has given fighters from outside the Han majority a new arena to excel, drawing on their heritage. Fans are beginning to recognize these athletes not just as Chinese fighters, but as representatives of their distinct cultures, adding a new layer of pride and narrative to Chinese MMA. Before diving into individual fighter profiles, it’s important to understand the combat traditions many of these minorities come from.

*Note: The terms Mongol and Mongolian are often used interchangeably, but there is a subtle distinction. Mongol refers to the ethnic group, which includes people of Mongol heritage living in both China (primarily in Inner Mongolia) and Mongolia (the independent country). Mongolian can refer more broadly to anything related to Mongolia—its nationality, language, or culture—but it is also commonly used to describe ethnic Mongols. In this article, Mongol is used when referring specifically to the ethnic group within China, while Mongolian is used in broader or international contexts.

Warrior Traditions of China’s Ethnic Minorities

Wrestling on the Grasslands and in the Mountains: While flashy Shaolin-style kung fu captures imaginations on film, in many fights with few rules it’s often grappling and wrestling that prevail. China’s minority regions, especially those on the borders, never lost their wrestling culture. In ancient times, mixed-style fighting competitions called Leitai (on raised platforms) were popular across China, blending strikes and throws. Over centuries, however, mainstream Chinese martial arts focused more on striking and forms, whereas many borderland peoples continued to prize wrestling skills.

For example, Mongolian Bökh wrestling has been practiced for hundreds of years by Mongols in Inner Mongolia (northern China) as well as in independent Mongolia. At traditional Nadam festivals in Inner Mongolia, bare-chested wrestlers in leather shoulder vests grapple in the grass – a spectacle of strength passed down from Genghis Khan’s time.

Similarly, in Xinjiang, Kazakh and Kyrgyz communities practice forms of belt wrestling (such as Kures) during celebrations, showcasing techniques to throw an opponent to the ground. The Tibetan people, known for their horsemen and warriors in history, also have indigenous wrestling games (for instance, at some Tibetan festivals, men engage in friendly wrestling bouts to entertain crowds).

The Yi “Hero’s Wrestling”: Among the Yi of Sichuan and Yunnan, wrestling is more than sport – it’s a cultural touchstone. Every year during the Yi Torch Festival, villages host wrestling competitions known as sani wrestling, where even children start grappling young, and women participate as well. This tradition of “festival wrestling” means many Yi grow up learning how to fight from a very early age.

One Chinese fighter noted that when he went to train in Yi areas, “even local farmers, these old women…have taken part in this kind of wrestling since they were maybe five years old” time.com. In Yi culture, the concept of the “hero” is celebrated – historically, Yi warriors wore a white-studded hero’s sash as a symbol of valor. This has carried into modern MMA: Yi fighters often don the traditional sash when celebrating victories to honor their heritage.

Many Yi martial artists grew up wrestling at local festivals, a tradition now translating into MMA success.

From Nomadic Combat to the Cage: The Kazakh minority in China (concentrated in the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture of Xinjiang) also boasts a strong wrestling pedigree. Kazakhs traditionally practiced Greco-Roman and freestyle wrestling, and even today many Kazakh youths compete in regional wrestling championships. This background is evident in fighters like Shayilan Nuerdanbieke, a Chinese Kazakh who trained in wrestling for six years and became a Xinjiang wrestling champion before turning to MMA.

The Kyrgyz and Uzbek minorities (also in Xinjiang) share similar wrestling traditions. For the Tibetans, a culture known more for Buddhism, there is also a history of toughness – Tibet had warrior monks and armies in the past, and in certain areas Tibetan styles of kickboxing and wrestling (sometimes integrated with the Chinese art of Shuai Jiao wrestling) have been preserved. Many Tibetan fighters cross-trained in Chinese Sanda (a kickboxing style that includes wrestling throws) as well.

What links these groups – Yi, Mongols, Kazakhs, Tibetans, etc. – is that grappling is ingrained in their cultures. This has given their athletes an edge in modern MMA, which heavily rewards wrestling ability and ground control. In fact, when MMA first arrived in Asia in the 1990s, Mongolian wrestlers dominated the scene. Today, we see a renaissance: fighters from wrestling-heavy minority backgrounds are rising to the top in China’s MMA circuits.

Of course, striking skills are important too – and many minority fighters also train in Sanda, Muay Thai, or boxing – but their wrestling base often makes the difference. Traditional martial arts events and ethnic sports games in these communities have effectively been grassroots MMA incubators, producing tough, competition-tested fighters ready to transition to professional MMA.

Standout Fighters: Champions of Minority Heritage

China’s current crop of MMA talent features numerous stars from minority backgrounds – both male and female – who have made headlines in the past year. Below, we profile some of these standout fighters, highlighting their achievements, training, and cultural heritage.

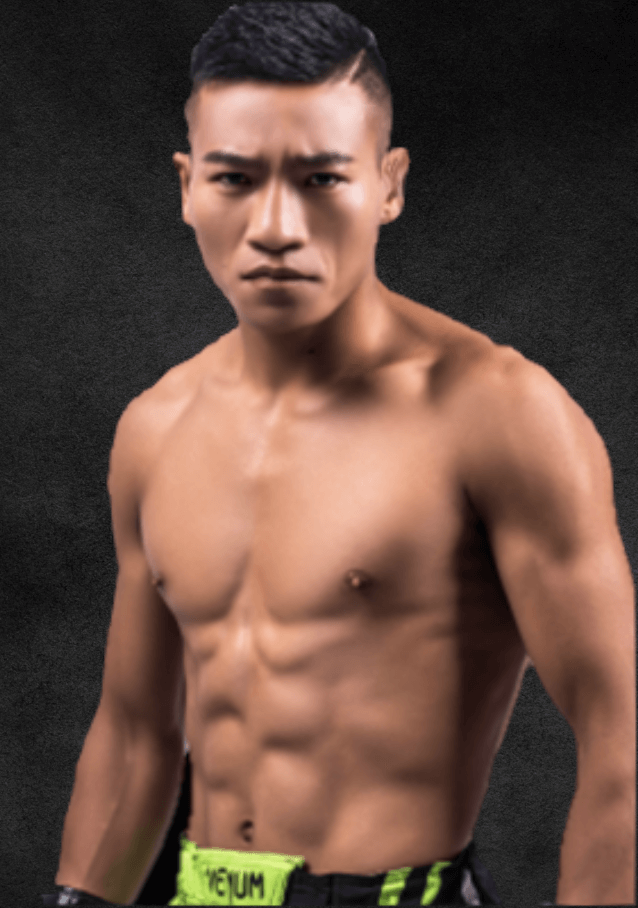

Hailaierke (Yi, China) – A 25-year-old fighter from the Yi ethnic group, Hailaierke shocked the Chinese MMA world in December 2024 by winning the JCK Bounty Tournament, one of China’s top MMA competitions. Stepping in as a last-minute replacement in the flyweight final, he knocked out the favorite, Shang Zhifa, in just 40 seconds to claim the 1 million RMB top prize.

In his victory speech, Hailaierke proudly wore the Yi hero’s sash and thanked “all my Yi compatriots for supporting me”. Hailaierke’s win was part of a larger trend – at that event, 4 of the 7 bout winners were Yi fighters.

After returning home to Liangshan (the Yi heartland in Sichuan), he received a hero’s welcome: villagers slaughtered pigs in his honor and thronged the streets to celebrate the “conquering warrior’s return.” Hailaierke attributes his fighting spirit to Yi culture: “I got into fighting because the Yi are a society of heroes…I wear the Yi heroes’ sash because it symbolizes valor and strength” time.com.

Trained under the famed Enbo Fight Club in Sichuan, which recruits many Yi and Tibetan youth, Hailaierke combines solid kickboxing with formidable wrestling defense – a testament to his upbringing in a wrestling-rich environment.

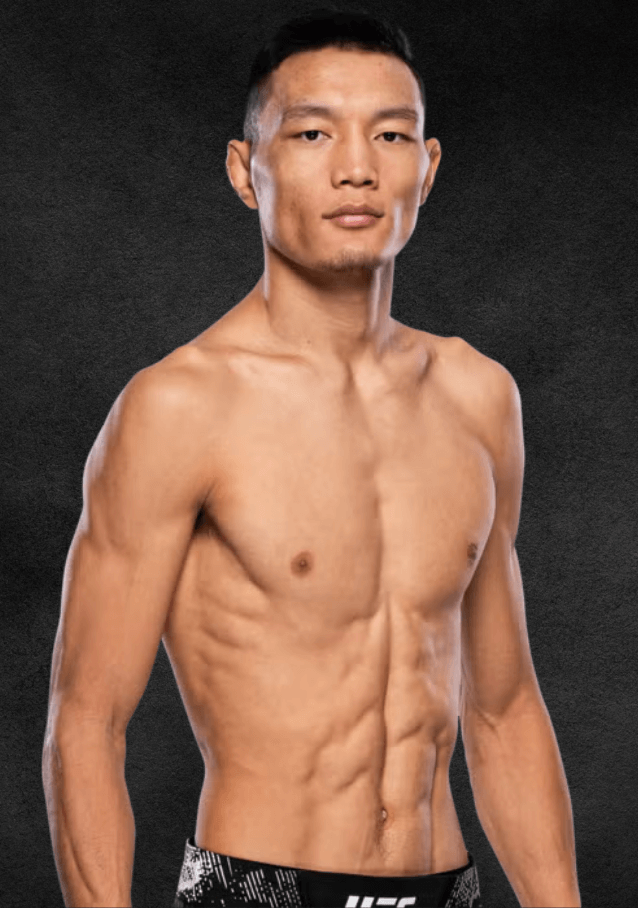

Su Mudaerji (Tibetan, China) – Also known by his Tibetan name Sonam Dhargye and nickname “The Tibetan Eagle,” Su Mudaerji became the first fighter of Tibetan heritage to sign with the UFC. Hailing from a Tibetan community in Sichuan’s Aba region, Su brought an impressive 12-3 record from the Chinese circuit (WLF Wars) into his UFC debut in late 2018.

He quickly made an impression with his dynamic striking – including a memorable knockout of Malcolm Gordon in 2021 that showcased his quick hands and timing. Su Mudaerji’s fighting style is primarily Sanda-based striking complemented by solid takedown defense, reflecting the blend of Chinese kickboxing and Tibetan toughness.

In July 2022, he engaged in an epic fight against Matt Schnell where Su’s lightning-fast punches had him on the verge of victory before Schnell caught him in a stunning comeback submission – a bout many called a Fight of the Year contender. Undeterred, the 27-year-old Su rebounded and most recently fought veteran Tim Elliott in late 2023. While he fell short in that match, Su remains one of the UFC’s most exciting flyweights.

He carries the pride of Tibet into the octagon, often speaking about inspiring other Tibetans. “All of the Tibetans from the region watch my fights and support me. My cause is that I want to bring honor for my people, team and the country,” he said tibetanjournal.com. Su Mudaerji’s success has already inspired other young Tibetan fighters to pursue MMA, proving that talent can emerge from even remote highland communities.

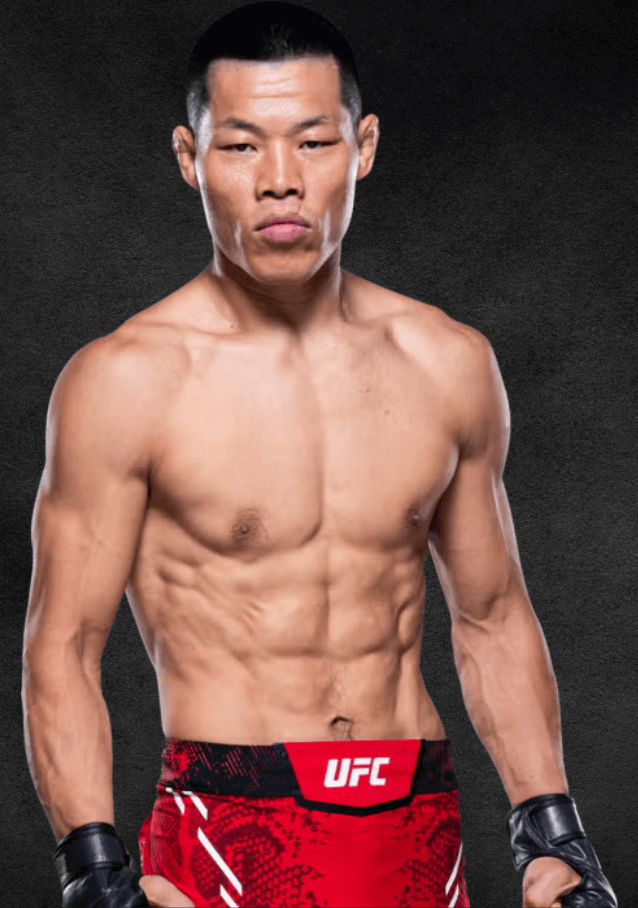

Shayilan Nuerdanbieke (Kazakh, China) – Nicknamed “Wolverine,” Shayilan is a Chinese national of Kazakh ethnicity who competes in the UFC’s featherweight division. Born in Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture of Xinjiang (near the borders of Kazakhstan and Mongolia), Shayilan grew up in a Kazakh community where wrestling is part of life. He trained in Greco-Roman wrestling from a young age, winning a regional 66kg wrestling championship in Xinjiang.

Inspired by watching Conor McGregor on TV, Shayilan transitioned to MMA in 2016 and amassed an astounding record of 37–9 on the Chinese regional scene. Now 30 years old, he has become one of China’s most experienced fighters with over 50 pro fights.

Since joining the UFC in 2021, Shayilan has notched notable wins, including victories over Sean Soriano and T.J. Brown. His style is a grinding wrestling attack – he likes to shoot for takedowns and control opponents on the mat, reflecting that Kazakh grappling pedigree. Outside the cage, Shayilan proudly maintains his cultural traditions – he even plays the dombra, a traditional Kazakh stringed instrument, to relax.

Fans in Xinjiang (both Han and Kazakh) cheer him on as a hometown hero. As MMA grows in China’s frontier regions, Shayilan Nuerdanbieke stands as a role model for many Kazakh youth that with hard work, one can go from local wrestling tournaments to the world’s premier MMA promotion.

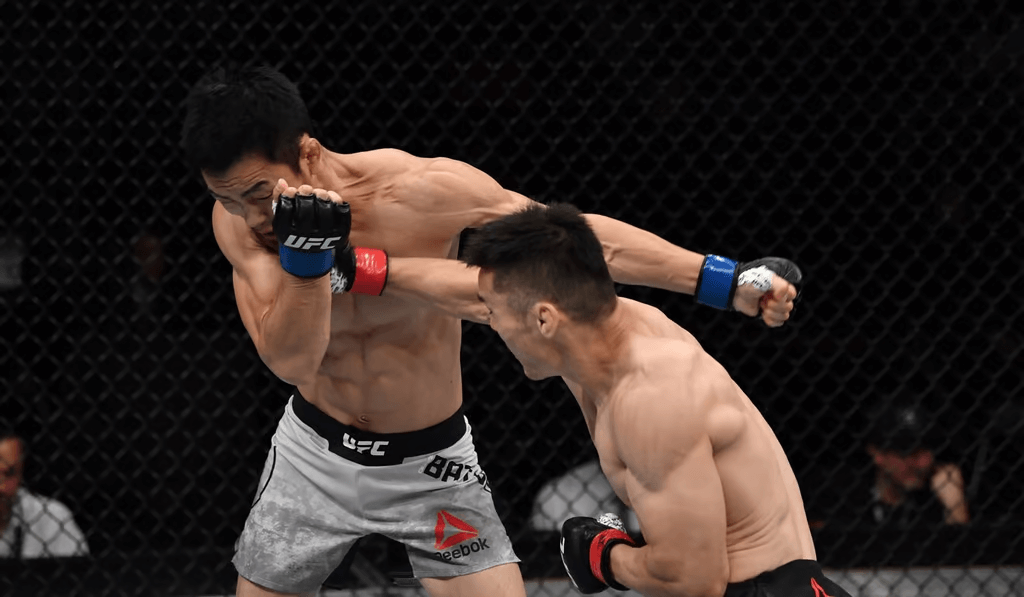

Alateng Heili (Mongol, China) – One of the vanguard of ethnic Mongolian fighters, Heili Alateng (often billed as Alatengheili) fights in the UFC’s bantamweight division. His nickname “The Mongolian Knight” reflects his Inner Mongolian heritage.

Alateng was born in 1991 and, following in his father’s footsteps, started training in Mongolian wrestling as a boy. He was scouted by a sports program and eventually transitioned to MMA, where his wrestling base gave him an advantage.

Alateng made his UFC debut in 2019 and immediately made waves by defeating Danaa Batgerel (ironically, a fighter from Mongolia) in a Fight of the Night performance. With a compact, stocky build, Alateng uses explosive takedowns and ground-and-pound, but he’s also evolved well-rounded striking. In 2022, he scored a 1st-round KO of Kevin Croom with a blistering punch combination.

Alateng trains part-time in Arizona (with Fight Ready gym) but often returns to Inner Mongolia and Beijing. He’s openly proud of being from Inner Mongolia, and Chinese MMA fans have embraced the “Mongolian Knight” as a standout. His success is a nod to the long history of Mongol wrestling producing combat sports champions.

Aori Qileng (Mongol, China) – Another ethnic Mongolian fighter, Aori Qileng fights in the UFC at bantamweight/flyweight and carries the ominous moniker “The Mongolian Murderer.” Born in Xilingol, Inner Mongolia, Aori grew up in a nomadic herding family and credits the hard rural lifestyle for his toughness.

He first trained in Sanda at a sports institute in Xi’an, but later embraced MMA for its broader skillset. Since joining the UFC in 2021, Aori Qileng has become a fan-favorite for his brawling style and iron chin. He earned his first UFC win in 2022 with a highlight-reel knockout, and most recently had a wild fight in mid-2023 that ended in a no-contest due to an accidental foul (after Aori delivered powerful strikes that unfortunately strayed low). With a record of 25-12, Aori is one of the most experienced fighters from China’s newer UFC generation.

Outside the cage, he often speaks of the grasslands of Inner Mongolia and how he “misses the endless sky” while training abroad. His very name “Ao Riqi Leng” means “universe” in Mongolian, symbolizing the big dreams he carries. Alongside Alateng, Aori Qileng represents the Mongol minority proudly on the international stage.

Li Jingliang (Xinjiang native, China) – While possibly of Han ethnicity, it’s worth mentioning Li “The Leech” Jingliang as a bridge between China’s west and the MMA world. Hailing from a small town in Xinjiang – a region with many Kazakh and Uyghur residents – Li grew up wrestling in local competitions before transitioning to Sanda.

As one of China’s top UFC fighters (a top-15 ranked welterweight at his peak), Li has trained with many wrestlers from minority backgrounds and helped shine a spotlight on Xinjiang as a hotbed for combat sports. With notable UFC wins and a fan-friendly style, Li paved the way for others from China’s frontier to believe they too can succeed internationally. (While his ethnic background isn’t clearly documented – some speculate he could have Kazakh heritage – Li primarily identifies as Chinese and focuses on unifying fans of all backgrounds.)

Yang Jianbing and Others (Hui & Manchu heritage, China) – A number of fighters from the Hui (Chinese Muslim) community and Manchu community have also emerged.

For instance, Ning Guangyou, winner of The Ultimate Fighter: China in 2014, is of Hui ethnicity and had a stint in the UFC – he came from a Sanda background, which many Hui in northwestern China excel at.

Song Kenan, a current UFC welterweight, comes from Inner Mongolia (though his ethnicity is Han, training alongside Mongolian teammates).

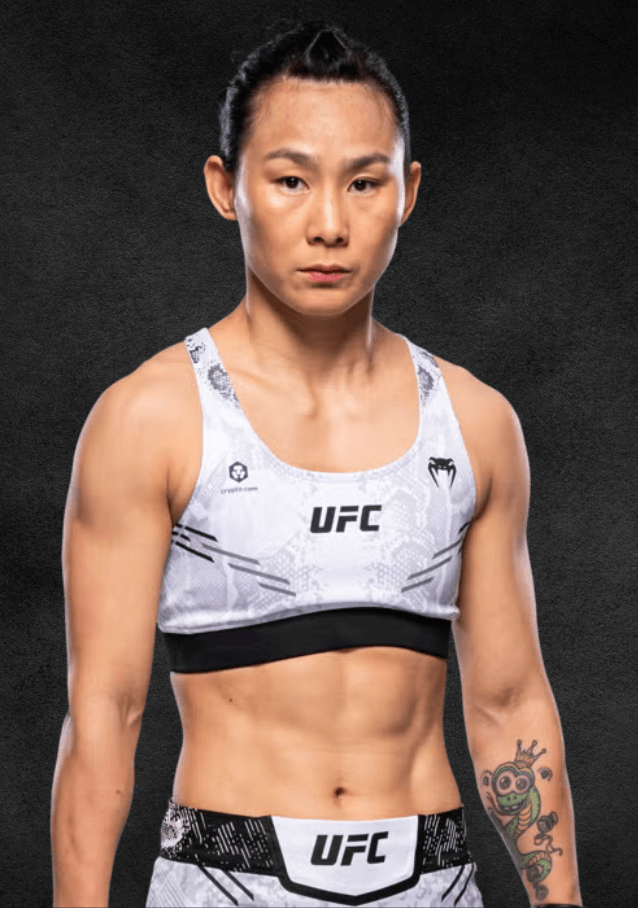

On the women’s side, Yan Xiaonan – the first Chinese woman signed by UFC – is of Manchu descent (an ethnic minority originating from northeast China). Yan rose to title contender status in 2023 with a string of impressive wins. Her success, along with that of strawweight champion Zhang Weili (who is Han), has helped grow MMA’s popularity among women in China, including those from minority regions.

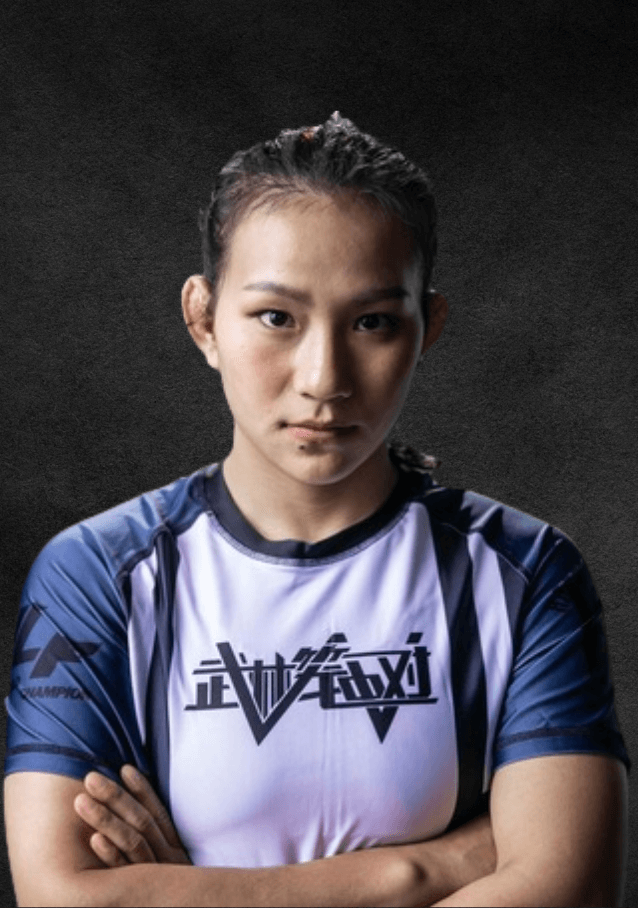

Hailai Wusamo (Yi, China) – Among female fighters, one rising star to watch is Hailai Wusamo, a young woman of Yi ethnicity from Liangshan, Sichuan. Hailai is currently 8-1 as a professional strawweight and riding a 7-fight win streak, making her one of China’s top-ranked female fighters.

Born in 2000, she came through the Enbo Fight Club system (her gym is literally named “Yi Fight Club / Monster MMA”). Hailai’s foundation style is wrestling, no surprise given she grew up in a Yi community where girls participate in wrestling festivities.

In October 2024, she headlined a women’s bout at the Galaxy MMA Cup in Macau, defeating Vietnam’s Nguyen Thi Truc in a showcase of powerful takedowns and ground control. At weigh-ins and events, Hailai sometimes wears traditional Yi clothing accents, proudly representing her heritage. With the technical skills to possibly enter a major promotion in the near future, she could become the first woman of an ethnic minority from China to break out internationally.

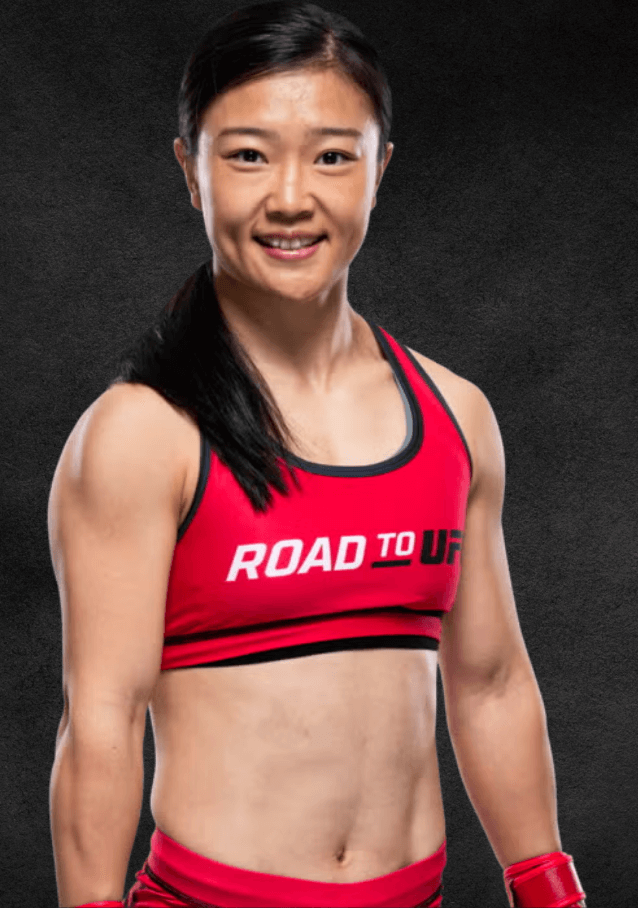

Shi Ming (Han, China) – Although not an ethnic minority herself, Shi Ming deserves mention for how she bridged Han and minority fighting traditions. A 30-year-old traditional Chinese medicine doctor from Yunnan, Shi Ming had a modest kickboxing career until she revamped her grappling by training with a U.S.-Iranian wrestling coach who took her to compete in Yi hill tribe wrestling tournaments.

The result? Her wrestling skills improved tremendously – enough to carry her to victory in the 2023 Road to UFC strawweight tournament. In November 2023, Shi delivered a stunning head-kick knockout in the final, earning a UFC contract.

She credited training at high altitude in Yunnan and sparring with local ethnic minority wrestlers for her improved toughness. Shi Ming’s story shows that the influence of minority martial arts isn’t confined to minority athletes alone – even majority Han fighters are learning from these traditional styles, further blending China’s combat heritage.

These are just a few examples – the list of notable minority fighters is growing rapidly. Others include Banma Duoji (Tibetan, a former Enbo prodigy who fought in ONE Championship at age 21), Niu Kang Kang (a female fighter of Hui background making a name in domestic promotions), A La Tenghui (another Mongol wrestler coming up through China’s ranks), and Tuerxun Jumabieke (Kazakh/Uyghur heritage, an early UFC pioneer from Xinjiang).

There are also ethnically Chinese fighters representing other countries: for instance, Angela Lee and Christian Lee, siblings of Chinese-Singaporean heritage, became world champions in ONE Championship representing Singapore. Their success has been celebrated by Chinese communities across Asia and shows how Chinese martial artists worldwide are contributing to MMA’s diversity. In Malaysia and Indonesia, fighters of Chinese descent (from diaspora communities) have also entered MMA – bringing a blend of local and Chinese fighting styles. This cross-pollination means that “Chinese MMA” is not limited to the PRC, but is a broader phenomenon of ethnically Chinese fighters thriving globally, and often connecting back to their cultural roots in China.

MMA’s Growth in Minority Regions: From Local Gyms to Big Leagues

The rise of these fighters is no accident – it’s fueled by the growth of MMA infrastructure in China’s minority-populated regions and the incorporation of local combat traditions into modern training. A decade ago, MMA was concentrated in big cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, which are overwhelmingly Han. But now, some of the most vibrant MMA scenes are in places like Sichuan, Yunnan, Inner Mongolia, and Xinjiang, where minority populations are significant.

One catalyst has been the emergence of gyms specifically recruiting and training minority talent. Enbo Fight Club in Chengdu, Sichuan, is a prime example. Founded by a former armed police officer, Enbo became famous for taking in impoverished or orphaned Yi and Tibetan boys from Liangshan and Aba areas and training them in MMA (as documented in a VICE feature).

Enbo’s fighters, such as the Tibetan prodigy Banma Duoji and many Yi champions (Degaxue, Gexipengchu, etc.), have dominated national tournaments. Other regional gyms have followed suit: Xibu Geda (Western Warriors) in Xinjiang focuses on nurturing local wrestlers (Kazakh, Uyghur, Hui) and turning them into MMA fighters; Xilinhot MMA in Inner Mongolia scouts wrestling meets for talent; and clubs in Yunnan work with the diverse ethnic groups there (Yi, Hani, Dai) to train well-rounded fighters.

Local governments and sports bureaus have also started supporting MMA events in these regions, seeing an opportunity to both develop sports and showcase minority culture. For instance, Lhasa (Tibet) hosted a regional MMA championship in 2023 that featured Tibetan and Han fighters and drew large crowds curious to see a “cage fight” in person.

In Xinjiang, promotions have held events in Ili and Urumqi, often preceded by exhibitions of traditional wrestling or dance. Even in small towns on the Sichuan-Yunnan border, one can find “cage fighting” nights as part of festival celebrations. At the Liangshan Torch Festival, alongside traditional Yi dances and horse races, they have staged MMA exhibitions where local fighters take on outside opponents – a way of honoring the Yi love of wrestling while entertaining modern audiences.

Ethnic sports festivals have been another conduit. The Chinese National Ethnic Games (held every four years) feature traditional sports of various minorities – Mongolian wrestling, Tibetan tug-of-war, Miao crossbow archery, etc. MMA coaches have smartly used these gatherings as scouting opportunities. A standout wrestler in a Nadam festival or a Yi torch festival might be recruited and given an offer to train professionally. As mentioned, Shi Ming’s coach actually entered her unofficially in Yi village wrestling bouts to sharpen her skills. This blending of old and new is accelerating the development of MMA talent pools.

Moreover, minority regions often sit at crossroads with neighboring countries where combat sports are popular – and fighters take advantage of that. Chinese Kazakh fighters sometimes cross into Kazakhstan for training camps and competitions, bonding with Kazakhstani fighters while still proudly carrying the Chinese flag into the ring.

In Inner Mongolia, some fighters train with Mongolian coaches from Ulaanbaatar to learn Sambo and judo. In Tibet and Yunnan, a few have gone to India or Thailand for cross-training. This exchange helps fighters from China’s peripheries gain broader experience. Promotions like ONE Championship have also held events near border areas (ONE has gone to Hefei and Chengdu) which gives local fighters exposure.

The result of all this is a surge of talent from places that were previously off the MMA map. Fans are now hearing ring announcers introduce fighters fighting out of Sichuan’s Liangshan, Xinjiang’s Altay, or Inner Mongolia’s Xilinhot – and often, those fighters are winning. The grappling foundation and raw athleticism honed in those locales make them formidable in the cage. And as infrastructure improves (more gyms, sponsorships, and smaller promotions feeding into larger ones), the pipeline of minority fighters is likely to grow. China’s UFC roster in 2025 is already more diverse than ever, and Chinese domestic leagues (like JCK, WLF, and Hero Fight) are brimming with minority champions.

Cultural Impact: Pride, Representation, and a New Narrative

The success of ethnic minority fighters in Chinese MMA has significance beyond just wins and losses. Culturally, it is reshaping narratives and fostering pride and unity in unique ways:

Resurgent Pride in Heritage: Within minority communities, seeing “one of their own” excel on a national or global stage has ignited pride. When Hailaierke returned to Liangshan with his championship, it wasn’t just a personal victory – it was a victory for the Yi people, who have sometimes felt marginalized or stereotyped in mainstream culture. As one analyst noted, this MMA success is “galvanizing interest in ethnic minority culture amongst sports fans as well as resurgent pride within those communities themselves” time.com. Youth in these areas can look up to fighters who share their language and customs, and feel that their heritage is an asset, not a hindrance. Fighters like Hailaierke and Su Mudaerji have become folk heroes back home.

Challenging Stereotypes: For a long time, ethnic minorities in China were often portrayed through narrow lenses – as exotic performers, or in political contexts. The emergence of minority MMA champions casts them in a new light: as modern sports heroes who are disciplined, courageous, and skilled. It also combats any notion that minorities are “backward” or less capable. In fact, in MMA they are leading. This flips the script and encourages more inclusion in sports.

Even the Han-dominated MMA fanbase has taken notice – Chinese fans on social media have rallied behind fighters like Aori Qileng and Shayilan, celebrating their victories just as passionately as those of Han fighters. “More and more Chinese fans are starting to recognize these minority athletes,” observes Hou Yu, a Chinese MMA analyst time.com. The idea of what a Chinese sports hero looks like is expanding to include many faces.

Unity through Sports: In a country where ethnic relations can be sensitive, sports provide a unifying arena. When a Chinese flag is raised after a UFC win or an Asian championship, it represents all of China – majority and minorities. Fighters themselves often express patriotism alongside ethnic pride. Chinese Kazakhs like Shayilan make sure to wrap themselves in the national flag even if they trained abroad, signaling that their achievements contribute to China as a whole.

This dual identity – proudly ethnic and proudly Chinese – is on display and can foster mutual respect. The mainstream media in China has cautiously begun highlighting these fighters’ ethnic backgrounds as positive stories of national integration (steering clear of any controversy, focusing purely on athletic achievement and colorful culture). For instance, TV segments have shown Mongolian wrestlers-turned-fighters demonstrating traditional wrestling moves, or Yi fighters teaching Mandarin-speaking hosts a phrase in Yi language, in a fun exchange. Such representation in popular media is meaningful for minority visibility.

Preserving Martial Traditions: Interestingly, MMA’s popularity might help preserve some traditional arts that were declining. When young Yi or Mongol kids see their local wrestling can lead to a pro sports career, they are more likely to keep practicing it. The Chinese MMA circuit has essentially created a demand for talent skilled in ethnic styles – which could incentivize local schools and clubs to keep those traditions alive.

We may see sani wrestling in Yi villages, Mongolian Bökh in Inner Mongolia, or Tibetan wrestling in Litang continue robustly, not just as cultural performances but as feeder systems for MMA. There’s a symbiosis where modern MMA training incorporates these folk styles (as with Shi Ming’s training in Yi villages), and in turn the success of fighters gives those folk styles a new platform.

Inspiration Across Borders: Ethnically Chinese fighters representing other countries also draw inspiration. For example, Angela Lee – born and raised in Canada and later Hawaii, but of Chinese and Korean descent – has spoken about how seeing Chinese fighters like Zhang Weili succeed made her feel proud of her Chinese heritage. The success of minority fighters in China can inspire ethnically Chinese athletes in Southeast Asia or the West to reconnect with their roots. We are already seeing collaborations: coaches of Chinese descent in the US are helping scout talent in China’s minority regions, and some fighters from China have traveled to train in gyms owned by Chinese diaspora coaches abroad. This global Chinese MMA network strengthens as each success story emerges.

Despite these positives, everyone is careful to avoid political overtones. The focus remains on culture and sport. The fighters themselves tend to stick to sharing cultural tidbits (music, dress, language) and thanking their communities for support, rather than wading into any sensitive issues. This ensures that the narrative stays a celebratory one – of diversity and heritage contributing to national glory – rather than a divisive one. In the case of MMA, it largely has been a win-win: the fighters get to be proudly themselves, fans get exciting new heroes, and Chinese MMA as a whole grows stronger and richer in stories.

Conclusion

From the grassland wrestling rings and mountain festivals to the bright lights of UFC arenas, China’s ethnic minority fighters have charted an incredible journey. In a country so dominated by the Han majority, it is the Kazakh grappler, the Yi wrestler, the Tibetan striker, and the Mongolian powerhouse who are adding new chapters to Chinese martial arts history. Their success is built on deep-rooted traditions of combat in their cultures – traditions now revitalized and repurposed for modern competition.

Over the last year, we have seen these athletes capture titles, earn international contracts, and inspire new followers. And importantly, they’ve done so while honoring their identities: wearing traditional sashes in victory, shouting out to hometown villages, and carrying the hopes of their peoples on their shoulders.

The growth of MMA in minority-populated regions – aided by clubs like Enbo and events like the Torch Festival fights – means the next generation is already in the pipeline. We can expect more “firsts” in the coming years: perhaps the first Yi fighter in UFC (two are already nearly there), the first Tibetan woman to win a major title, or a Kazakh Chinese athlete becoming a world champion. Each will further cement the idea that MMA in China is not just about one style or one ethnicity; it’s a melting pot of all the martial legacies within China’s borders (and even its diaspora).

In Chinese philosophy, martial arts were often seen as a path of personal betterment and harmony between peoples. In a modern twist, the octagon has become a place where a plurality of Chinese cultures coexist and shine. Ethnic minority fighters are shaping a narrative of diversity and resilience in Chinese MMA. They are showing that a warrior’s spirit knows no ethnic boundaries – it can be found in a nomad from Inner Mongolia, a farmer from Liangshan, a doctor from Kunming, or a herder’s son from Ili. And when given the opportunity, those spirits will fight their way to glory, to the cheers of a proudly diverse nation.

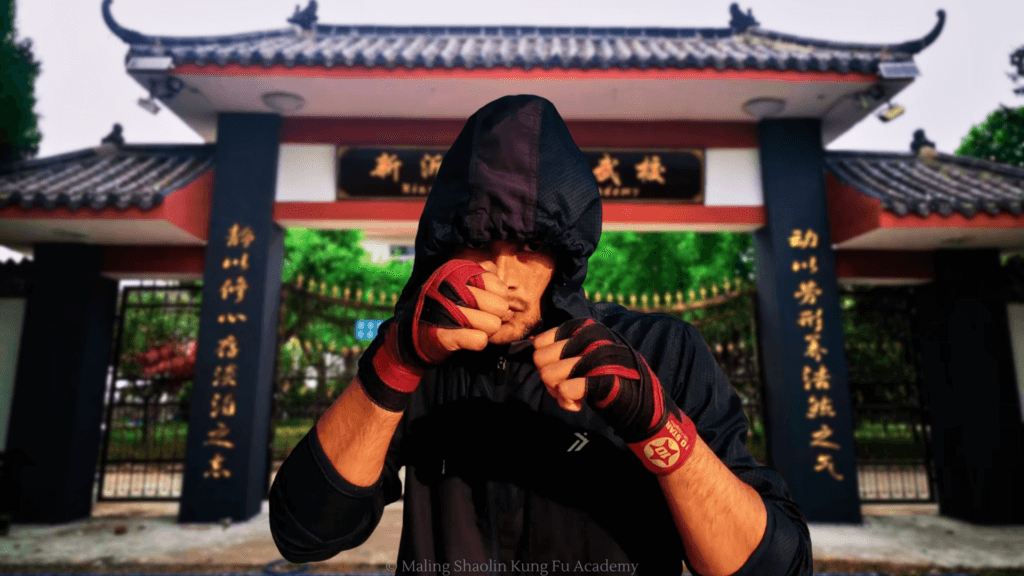

Train Where Tradition Meets the Future of Combat

As we’ve seen throughout the rise of ethnic minority fighters in Chinese MMA, success in modern combat sports often begins with a deep connection to traditional martial arts. From the high-altitude wrestlers of Liangshan and the grassland grapplers of Inner Mongolia, to the Sanda kickboxers and Shuai Jiao throwers redefining the global MMA landscape, China’s cultural diversity continues to shape the next generation of fighters.

At Maling Shaolin Kung Fu Academy, we honor this powerful fusion of heritage and innovation. Located in the heart of rural China, our school welcomes students from around the world to train in a variety of traditional and modern combat disciplines. Whether your interest lies in refining your striking, sharpening your takedown game, or building a complete MMA foundation, our curriculum offers a unique opportunity to study at the crossroads of ancient martial wisdom and modern fight science.

Our training programs include:

- Sanda (Chinese Kickboxing): A dynamic striking art with punches, kicks, sweeps, and throws—perfect for MMA base development.

- Shaolin Kung Fu: Build speed, explosiveness, and agility with traditional forms and combat applications from the legendary Shaolin Temple.

- Tai Chi: Train balance, timing, and internal control—many fighters are now turning to Tai Chi for its subtle but powerful movement principles.

- Wing Chun: Develop close-range strikes, trapping, and rapid-fire hand techniques ideal for in-fighting and clinch control.

- Baji Quan: Known for explosive power and devastating elbow and shoulder strikes—perfect for adding short-range impact to your game.

- Bagua Zhang: Enhance footwork, circular movement, and evasiveness—valuable tools in MMA’s fast-paced exchanges.

- Xing Yi Quan: Train structure, direct power, and forward pressure—excellent for aggressive striking strategies.

- Qi Gong: Strengthen your internal energy, breathing, and body awareness—boosting recovery, focus, and overall performance.

- Strength & Conditioning, Sparring, and Cross-Discipline Drills – Designed to improve fight readiness across disciplines.

Whether you are an aspiring MMA competitor or a passionate martial artist seeking deeper cultural immersion, training at Maling Shaolin Kung Fu Academy offers the tools, community, and experience to take your skills to the next level—surrounded by the same spirit of resilience and cultural pride that fuels China’s rising champions.

Ready to step into your own martial arts journey?

Train where warriors are made.

Train at Maling Shaolin Kung Fu Academy.

🔥🌏💪