In Part 2 of our featured article from Martial Arts Magazine Australia, Issue 8, we continue our exploration of the Shaolin Temple’s martial system by unpacking the inner framework of its training philosophy.

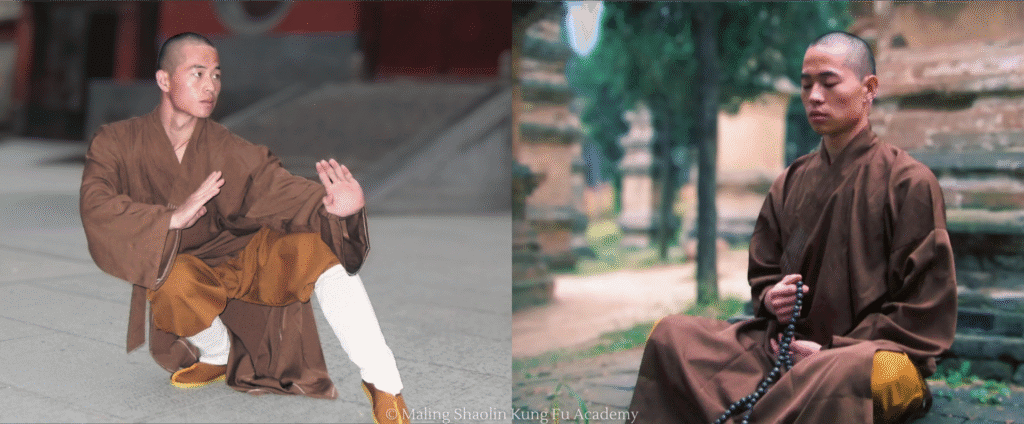

This section breaks down five of the major categories of Shaolin skill—neigong, waigong, yingong, qinggong, and qigong—and explores how internal and external practices are integrated into one unified system. With insights from Maling Shaolin Kung Fu Academy and 32nd-generation Master Shi Xing Jian, this part examines how physical power, breath control, mental focus, and movement precision all come together in true Shaolin training.

A System Both Broad and Deep

Ask a hundred martial artists what Shaolin Kung Fu is, and you might get a hundred different answers. Some will say it’s a fighting style. Others will say it’s a philosophy. Some picture high jumps and whirlwind kicks. Others think of iron palms breaking bricks or monks sitting in meditation under waterfalls. They’re all correct—and incomplete.

Shaolin Kung Fu is a system. A vast one. It is both external and internal, soft and hard, ancient and evolving. Rooted in Chan Buddhism (Zen), it blends physical combat techniques with spiritual discipline, emphasizing mind-body unity. To truly understand what is taught at the temple, we must look not just at what is practiced, but how it’s practiced—and how the layers of that practice connect.

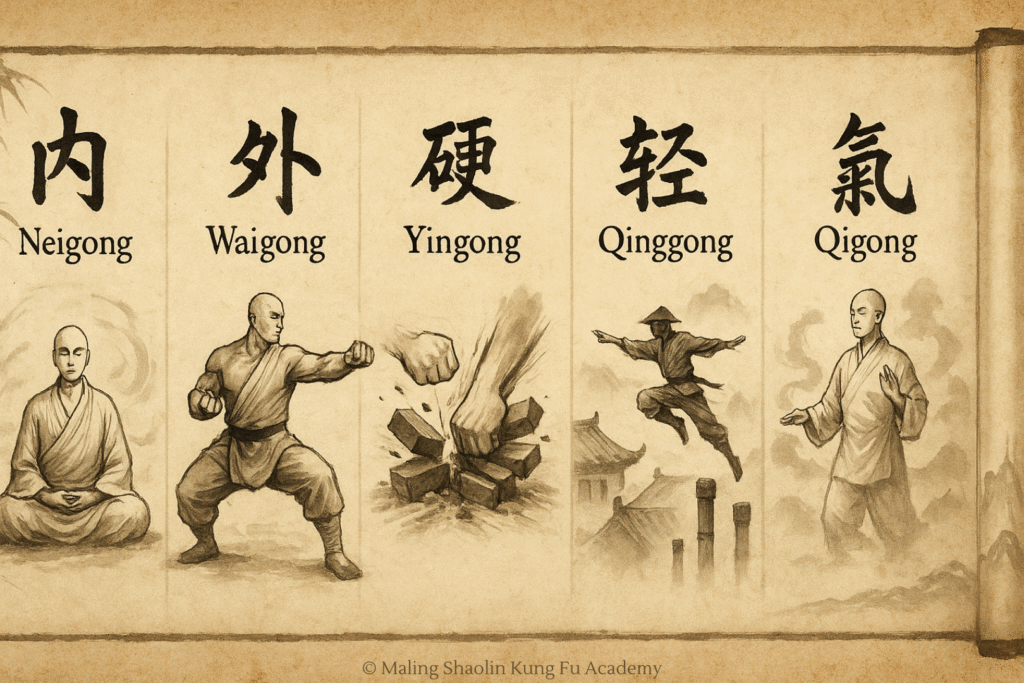

Shaolin martial arts can be broadly divided into five core categories, each contributing to a different aspect of the practitioner’s development. The first is neigong (内功)—internal skill—the cultivation of internal energy: jing, qi, and shen. This is the energetic and meditative foundation that gives depth and longevity to all practice. Next is waigong (外公)—external skill—the training of the physical body: muscles, bones, tendons, stamina, strength, speed. External skill is what the world sees, but it is only the surface. Then there is yingong (硬功)—hard skill or body conditioning—the forging of the body to withstand pain, impact, and stress. This includes practices like Iron Shirt, Iron Palm, Golden Bell, and others. It develops resilience and force through intense physical conditioning. The fourth category is qinggong (轻功)—the cultivation of agility, balance, and weightless movement. It trains the body to move as if floating, with control and responsiveness. Finally, qigong (气功)—energy work—is the breath-focused art of nurturing life energy. It spans both martial and medical realms, encompassing vitality, awareness, and harmony within the body.

It’s common to hear people confuse qigong and neigong, especially outside of China. While the two are closely related, they serve different functions within Shaolin training. Qigong is often practiced for health and wellness. Movements are slow, deliberate, and focused on breath control and internal awareness. A person recovering from illness may practice qigong to strengthen their lungs and circulation. An office worker who never exercises might begin qigong and feel, within weeks, like they’ve discovered a new body—more open, light, rested, and alive. Their sleep improves. Their digestion improves. Even their mood stabilizes. But this is only the beginning.

For a martial artist, qigong is not a side practice—it is foundational. It heightens awareness of subtle body changes, enhances longevity, and refines breathing patterns. It teaches control, calmness, and timing. Still, it is not meant for direct combat application in its raw form.

Neigong, by contrast, is martial in nature. It is the cultivation of internal force—neili—through breath, intention, and movement. It powers strikes from the inside. A master with strong neigong may appear still, but deliver a blow that penetrates deeply, as if the force were generated from the center of the earth. Neigong is quiet. It is not flashy. But over time, it allows the practitioner to unify the body, breath, and mind into a single, powerful movement. It’s what turns a movement from choreography into real combat capability.

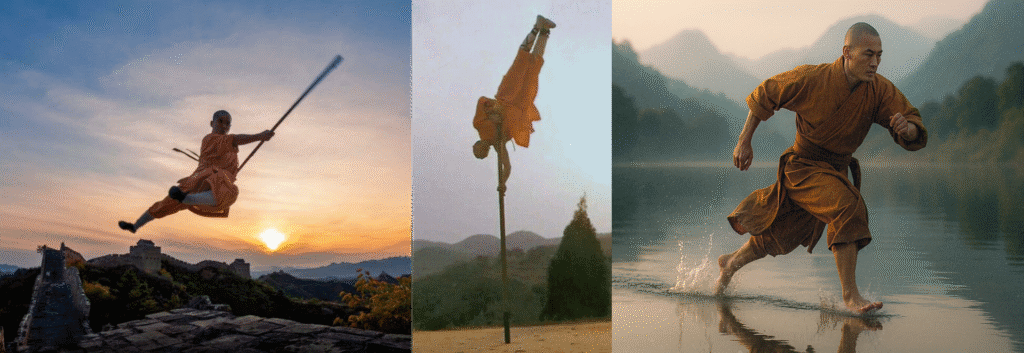

Qinggong is one of the most mysterious and misunderstood aspects of Shaolin training—often exaggerated in fiction, but grounded in real, physical principles. To understand qinggong, we must first move beyond the fantasy of monks leaping across rooftops or running up bamboo stalks. These images, while dramatized, are rooted in the awe-inspiring agility of real masters whose movement seems to defy gravity—not because they fly, but because they have trained their bodies to move with perfect control.

Qinggong involves much more than jumping high. It is about lightness of step, fluidity in transitions, responsiveness to contact, and the ability to “float” through obstacles rather than fight against them. A skilled practitioner of qinggong develops high sensitivity—not just in muscle or reflex, but in the nervous system. They feel the ground differently. Their body anticipates movement with grace. They don’t jerk or stumble; they flow, almost like water.

For example, if such a practitioner is pushed, their body doesn’t resist stiffly or recoil in shock—it instinctively redirects, gliding away with control. Their body moves before the mind commands it. This kind of subconscious reaction is trained over years of focused movement, spatial awareness, and energy management. Some of qinggong’s more advanced feats include running across short distances of water (水上漂), bounding over narrow poles (穿林跃桩), climbing walls in quick succession (飞檐走壁), or darting through forests and terrain with almost inhuman speed (草上飞). While these feats are difficult to believe without seeing, they are not magical. They are a product of agility, repetition, breath control, and total body synchronization.

Even in daily life, qinggong leaves an imprint. Practitioners walk lighter. Their posture is upright. Their footfalls are silent. They are less likely to bump into things. The sensitivity they develop spreads into every aspect of their awareness.

Where qigong and neigong build the internal structure, waigong builds the external frame. This is the world of stances, forms, punches, kicks, endurance, and strength. Waigong develops muscle memory, tendon and joint mobility, overall power, and speed. But when practiced without internal integration, waigong can become stiff—like a robot mimicking kung fu. The breath is held, the movement locked. It may look impressive, but it lacks true spirit.

Adding neigong to waigong makes the movement fluid and alive. Breath enters the motion. Transitions become natural. Power is released, not forced. The practitioner learns not just how to move, but how to express intention through movement.

Yingong, or hard skill, is perhaps the most physically punishing category. It includes iron body conditioning—fists, shins, arms, abdomen, even the whole body. Techniques like 铁砂掌 (Iron Sand Palm), 金钟罩 (Golden Bell), and 铁布衫 (Iron Shirt) belong here. Through repeated impact training, the body is transformed into a weapon—dense, resilient, and fearlessly conditioned.

In addition to the broad training categories, Shaolin is also defined by several key movement principles—the mechanical and philosophical underpinnings of its technique. One such principle is 出招进退,拳打一条线—attack and retreat follow a straight line; punches are delivered along a single line. This is the visual signature of Shaolin movement. Whether advancing or withdrawing, the body maintains alignment. Stances are upright, transitions clean. Forms flow like a thread pulled taut—each movement locked into the next, reducing wasted motion and maximizing force. In combat, this allows quick directional change, control of distance, and rapid execution.

Another is 非曲非直,滚出滚入—neither too curved nor too straight; roll out, roll in. This principle governs joint movement, particularly the wrists and elbows. A wrist that is too stiff becomes brittle; too bent, and it limits tendon extension. Both weaken strikes and defenses. Instead, Shaolin emphasizes a naturally curved strength—an active, relaxed readiness that allows for spiraling, coiling energy. When executed properly, power is released from the waist and spine, rolling outward into strikes or inward into redirections.

There is also 拳打卧牛之地—strike within the space where an ox lies. This poetic phrase refers to compact efficiency. A Shaolin practitioner should be able to execute all strikes, steps, and turns within a space no bigger than a cow lying down. It’s not just about economy—it’s about adaptability in tight quarters, where there’s no room for error or grand gestures. Small space training sharpens awareness, refines footwork, and forces precise technique. A master can fight with full effectiveness in a hallway, a courtyard, or a mountaintop ledge.

Finally, 内外兼修,攻防技击高—cultivate both internal and external; achieve excellence in offense, defense, and combat. This is the ideal state of Shaolin practice: balance and mastery in all directions. It reflects not just physical technique, but the integration of breath, spirit, intention, and body. Attack and defense are not separate. Hard and soft are not opposites. Internal and external work together—sharpening the mind, stabilizing the body, and elevating the martial artist to their fullest expression.

Shaolin martial arts are not a matter of technique alone. They are a way of refining your senses, building your body, calming your mind, and expanding your awareness. They don’t ask you to become someone else. They ask you to become more fully yourself—stronger, clearer, more connected.

Now that we’ve explored the structure and philosophy behind the training, it’s time to look at what is actually taught. In the final section, we’ll dive into the forms, weapons, and styles that make up the tangible, physical curriculum of Shaolin Kung Fu.

Want To Read More?

Check out Part 1, All Martial Arts Under Heaven Come from Shaolin?, and Part 3, Styles, Forms, and Weapons of Shaolin If you want to support the magazine, check out the digital or, if you live in Australia, printed copy of Martial Arts Magazine Australia (MAMA), Issue 8 on their website.

Disclaimer: We do not receive any financial compensation from the sales or distribution of Martial Arts Magazine Australia, Issue 8, which features the referenced article. Our sole intent is to share our contribution to this publication with our readers.