Table of Contents

- Flowing Forms: Waterbending’s Roots in Tai Chi

- “Be Water, My Friend”: Turning Opponents’ Strength Against Them

- Healing with Qi: Waterbending and Traditional Chinese Medicine

- Water Tribe Culture: Parallels to Indigenous Arctic Peoples (and Hints of Chinese Influence)

- Gentle Tide and Raging Tsunami: The Dual Nature of Water (and Waterbenders)

- Conclusion: Between Academic and Mythic – The Legacy of Waterbending

Introduction

In Avatar: The Last Airbender, Waterbending is more than splashy spectacle—it’s a living art rooted in real traditions. Its graceful arcs and sudden surges draw from Tai Chi (Taijiquan) and the healing logic of Traditional Chinese Medicine, where breath, qi flow, and acupressure guide both power and repair. We’ll trace how waterbenders turn an opponent’s force back on itself (think Sun Tzu and Chinese swordsmanship), why Sokka’s strategy and training fit the Water Tribe ethos, and how the Tribes echo real Arctic seafaring cultures—layered with Chinese influences like Yin–Yang, Tui and La (push and pull), and the lunar rhythm. We’ll also explore water’s paradox—gentle healer and devastating flood—from Katara’s cures to the moral shadow of bloodbending. Finally, we’ll link the moon’s pull on Waterbending to Wu Xing (Water, winter, rest, regeneration). This deep-dive blends scholarship and fandom to reveal how Waterbending bridges fantasy and the real martial and medical wisdom of our world.

Spoiler Warning:

This article may contain detailed discussion of storylines, characters, and lore from Avatar: The Last Airbender, The Legend of Korra, and minor points related to the comics and novels. If you haven’t finished the series and wish to avoid spoilers, we recommend returning to this piece after watching both shows.

Water.

“Our strength comes from the Spirit of the Moon; our life comes from the Spirit of the Ocean.”

-Princess Yue

Flowing Forms: Waterbending’s Roots in Tai Chi

It’s no secret that each bending art in ATLA was modeled after a real martial art, and Waterbending’s “bending form” is based on Tai Chi. Tai Chi (Taijiquan) is an internal Chinese martial art famous for its slow, elegant forms and flowing motions – perfect for the element of water. In fact, the creators consulted martial arts expert Sifu Kisu to design bending styles, and he chose Yang-style and Chen-style Tai Chi for waterbenders. The result on screen is a style emphasizing continuous, circular movements, grace, and adaptability – hallmarks of Tai Chi. Water flows smoothly; so do the waterbenders, never stiff or abrupt. Their stance transitions and arm motions evoke the feeling of a calm river that can suddenly become a powerful wave.

Tai Chi’s philosophy is “softness overcomes hardness,” and we see this in every Waterbending fight. Rather than meeting force with force, waterbenders prefer to yield around an oncoming attack and redirect it. “Tai Chi’s softer style [is] characterized more by control than aggression,” as Sifu Kisu notes. It’s “less about strength and more about alignment, body structure, breath, and visualization” – exactly the qualities Katara and other waterbenders demonstrate. Watch Katara’s sparring sessions: she stays light on her feet, breathing steadily, flowing with each strike. When Zuko or Azula hurl fire at her, Katara often pivots or spins away, guiding water in a curved path to intercept or deflect. This is classic Tai Chi strategy – using 柔 (rou, softness) to overcome 刚 (gang, hardness). A traditional saying in Tai Chi is that “four ounces can deflect a thousand pounds,” meaning a small flexible force can redirect a great powerful force by using its own momentum. We see this when waterbenders turn an enemy’s big attack against them. For example, catching a massive fire blast in a water stream and spiral it away, rather than blocking it head-on. As the Avatar Wiki observes, “a waterbender finds that softness and breathing are more effective than hard aggression, just as a practitioner of taijiquan does,” and the qi (energy) must flow through the body “like water,” driven by internal balance. In other words, waterbenders move with the water’s natural energy, not against it, embodying the Taoist ideal of harmony with nature.

Even the source of Waterbending in the Avatar world reflects Tai Chi philosophy. Waterbenders learned from the Moon and Ocean, observing the push-and-pull of tides rather than from a beastly, muscular animal (contrast this with Earthbenders learning from badgermoles or Firebenders from dragons). This origin story emphasizes symbiosis and guiding nature rather than dominating it. In Tai Chi and Taoism, water is often used as a metaphor for the ideal way to act: yielding, adaptive, yet unstoppable. Master Pakku tells Aang and Katara to think of water as following its nature – it can “flow or crash,” as Bruce Lee famously said. This mindset is fundamentally Chinese in origin, echoing Daoist classics like the Dao De Jing, which praises water’s humility and power. Indeed, in Taoist philosophy water is associated with the element Yin, embodying qualities of softness, depth, and receptivity. Katara’s calm but firm style and her nurturing disposition both speak to water’s Yin nature – but as we’ll explore, Yin always has a bit of Yang, and water’s gentleness can turn fierce when provoked.

“Be Water, My Friend”: Turning Opponents’ Strength Against Them

As stated, one of Waterbending’s signature combat techniques is using an opponent’s own energy against them. Rather than smashing through an enemy’s defense, a skilled waterbender finds the path of least resistance – like water finding a crack – and redirects the incoming force. Sun Tzu’s Art of War could be describing a waterbending duel when it says: “Military formation is like water – water avoids the high and goes to the low, the form of an army is to avoid strength and attack weakness…so a military force has no constant form, just as water has no constant shape. The ability to adapt and seize victory by changing according to the opponent is called genius.” In practical terms: avoid what is hard and strike at what is soft. Waterbenders excel at this. If a foe attacks head-on, the waterbender sidesteps and guides the foe’s momentum off course – metaphorically letting the enemy slip on the “wet ice” of their own aggression. We often see Katara or Aang standing poised, waiting for the right moment when the enemy overextends, then with a fluid turn of the torso and a swing of the arm, they send a tendril of water to trip or slam the opponent using that very momentum. This is the same concept taught in Tai Chi sparring (Push Hands): lead your opponent into emptiness, neutralize their force, then counter. It’s the martial embodiment of “柔能克刚” – softness can overcome hardness.

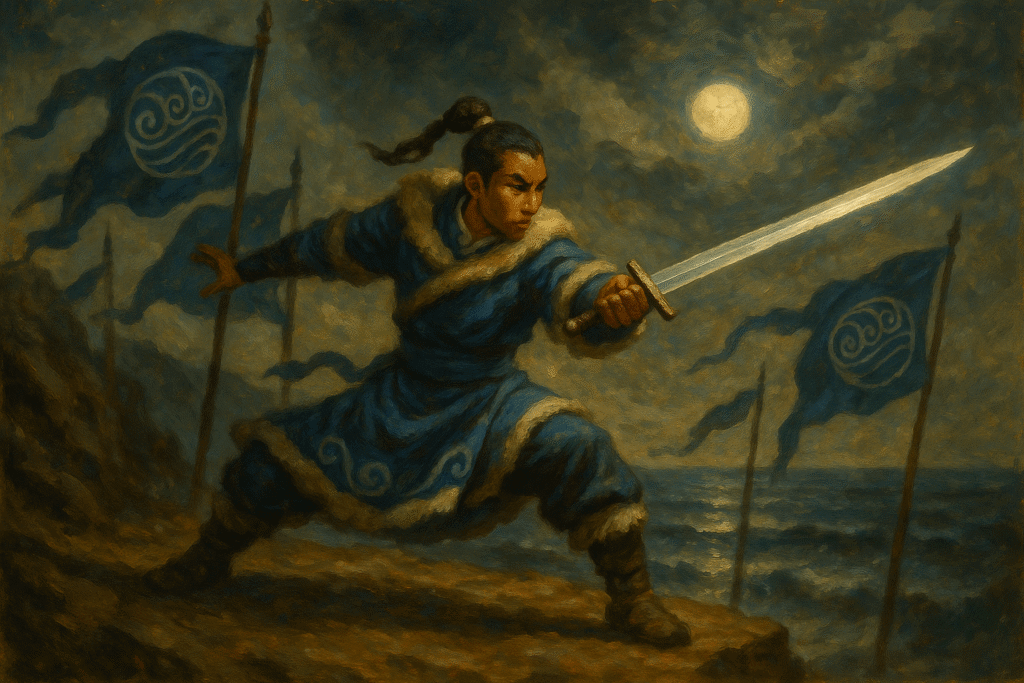

In Chinese swordsmanship, particularly with the elegant straight sword (jian), there is a similar emphasis on deflection and redirection. A master swordsman doesn’t brutishly hack; he/she uses subtle angles and timing to guide the enemy’s blade away and leave them open. The Water Tribe’s non-bending warrior, Sokka, learns swordsmanship from Master Piandao, who teaches him to use creativity, feints, and the environment – essentially the “waterbending” approach to sword fighting. Piandao even has Sokka practice calligraphy and paint landscapes to understand flow and adaptability, mirroring how a general studies terrain or how a Tai Chi practitioner feels the energy in movement. Sokka, though not a waterbender, embodies Water Tribe strategy in battle: he’s not the strongest or most aggressive fighter, but he’s clever and agile.

Think of Sokka’s plans (like using the slurry pipeline to disable the Fire Nation drill, or inventing a submarines invasion during the Day of Black Sun) – they consistently use indirect tactics to turn the Fire Nation’s might against itself. This is pure Sun Tzu. The Art of War advises, “If your opponent is of choleric temper, seek to irritate him. Pretend to be weak, that he may grow arrogant.” Sokka often plays the fool or uses jokes to throw enemies off (like Piandao himself noted humor as part of Sokka’s unconventional tactics). Another Sun Tzu dictum: “So in war, the way is to avoid what is strong and strike at what is weak.” Waterbenders do exactly this by attacking at unguarded angles. They literally “flow like water” around a strong defense. Aang’s fight with Ozai in the finale showcases this: when Aang finally embodies a fully realized waterbender’s approach, he doesn’t take Ozai’s fire blasts head-on. Instead, he creates swirling element shields, uses circular sweeps to douse flames, and waits until Ozai is off-balance to restrain him. It’s a visual translation of the Sun Tzu line “water shapes its course according to the nature of the ground; the warrior works out his victory in relation to the foe”.

For a waterbender, turning an opponent’s energy against them isn’t just a trick – it’s almost a spiritual principle. The Water Tribe’s patron spirits are the Moon and Ocean, named Tui and La (推拉), which mean “Push” and “Pull” in Chinese. These two forces are in eternal dance, one advancing while the other yields, then trading roles. Waterbenders channel this push-pull cycle in combat: every attack (push) they face is met with a yielding (pull) movement, which then rebounds as their own counter-attack (a new push). It’s a perfect feedback loop of energy. This concept also appears in Chinese sword arts like Taiji Jian (Tai Chi sword) and in Judo (a Japanese art, but influenced by similar principles): use the opponent’s force, add a little to it, and send it back to topple them. We can see a direct parallel in how Katara defeats Azula during the climactic Agni Kai: Azula launches a furious lightning strike at Katara; Katara uses water to redirect that lightning (literally taking Azula’s energy and turning it back on her, much as Iroh taught Zuko to do). In a less literal sense, Katara ends up defeating Azula by outsmarting her – Azula’s fire was overwhelming, so Katara lured her over a water grate and used Azula’s reckless charge (her psychological energy) to trap her in ice. It’s a very “water” victory: win through cunning and patience rather than sheer force.

Sokka’s strategic mind and Piandao’s teachings also tie into this theme. Sokka, ever the planner, often cites the need to “think like our enemy” and find ways to use their strength against them (like turning the Fire Nation’s own ships into a bombing fleet against the drill). His approach is akin to Sun Tzu’s advice to know the enemy and know yourself. Even though Sokka wields a sword of meteorite iron, he fights like a waterbender at heart – flowing around heavier opponents, redirecting their strikes, and winning through timing and brains. In a way, Sokka writing his own “Water Tribe Art of War” wouldn’t be far-fetched (the fandom has even joked about Sokka authoring a strategy book akin to Sun Tzu). The show subtly affirms this when Sokka becomes a master swordsman; Piandao acknowledges that Sokka’s ingenuity and adaptability are his greatest strengths, not brute strength. Those are very Water Tribe traits.

Healing with Qi: Waterbending and Traditional Chinese Medicine

Beyond combat, Waterbending encompasses a healing art that is richly informed by Chinese concepts of qi circulation and meridians. In Book 1, Katara discovers she has the ability to heal wounds by channeling water over them. This isn’t just fantasy magic – it’s directly based on Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practices, where balancing the flow of qi (life energy) through the body’s meridians is key to health. In the show’s canon, waterbenders use healing by guiding water (and energy) along the injured person’s chi pathways, unblocking and restoring flow. As one analysis notes, “The healing technique Katara learns at the Northern Water Tribe is based on the TCM idea of qi and qi meridians… the body has natural patterns of chi circulating in channels called meridians. These meridians are what the waterbenders use for healing”. So when Katara places her hands over Aang’s wound and the water glows, she’s essentially performing energy work akin to qigong healing or Reiki, directing life-force to where it’s needed.

This idea is reinforced by the presence of Ty Lee’s chi-blocking technique in the series. Ty Lee (a non-bender) strikes certain pressure points on a bender’s body to interrupt their chi flow, rendering them unable to bend temporarily. This is a straight lift from Chinese martial arts and medicine – the concept of acupressure points (or dim mak in martial lore). Ty Lee’s strikes hit the same meridians that acupuncturists target to either disrupt energy or, in healing contexts, to stimulate it. The show explicitly connects the two: the very points Ty Lee jabs to paralyze Katara’s bending are the ones Katara would concentrate water over to heal someone. It’s a great example of the duality in TCM/martial arts: points that heal can also harm. Chinese martial artists knew this well; many were also doctors. A saying in martial arts is “before learning to destroy, learn to heal.” The logic is that you must understand the body’s energy network to fix it and to exploit it in combat. This mirrors Katara’s journey – she trains as both a fighter and a healer.

In Chinese history and legend, martial arts and medicine were deeply intertwined. Shaolin monks, for instance, practiced bone-setting and herbal medicine alongside their fighting skills. Many famed kung fu masters were also physicians, since injuries were common and knowledge of the body was crucial. As one source puts it, “Traditional Chinese medicine and Eastern martial arts go hand in hand throughout history… Indeed, a well-known historical fact is that the best doctors in the Far East were also well-known martial artists.” The reasoning is clear: Qi (Chi) is central to both healing and fighting. In TCM, illness is seen as a blockage or imbalance of qi in the meridians. In martial arts, generating power or incapacitating an enemy often involves manipulating qi – either your own (to generate internal power) or the opponent’s (by striking their acupoints). Avatar’s Waterbenders embody this unity. Katara learning healing in the North Pole is essentially learning TCM energy work. She even uses terms like “energy” and focuses with meditation-like calm as she heals. Meanwhile, when she later encounters Ty Lee’s chi-blocking, she immediately recognizes the concept (“She hit my pressure points!”) – her healing knowledge gave her insight into what Ty Lee did. We can imagine that if Katara studied her healing scrolls deeply, she’d see diagrams not unlike a Chinese meridian chart, showing flows of energy in the body.

Water, in many cultures, is seen as the element of life and restoration – think of the importance of water in baptism, cleansing rituals, or simply in hydrating crops and people. In Chinese five-element theory (Wu Xing), water is linked to the kidneys and the essence of life (jing), symbolizing regeneration and storage of vitality. Fittingly, in Avatar, waterbenders alone (besides the Avatar) have the ability to directly restore life energy via healing. Katara’s identity beautifully balances warrior and healer, and this dual role has a real-world parallel in the concept of the warrior-physician. In ancient martial schools, practitioners learned how to mend dislocated joints, bandage wounds, and use herbs or acupuncture to treat injuries – because who better to fix a injury than someone who knows exactly how it was inflicted? There’s even a Chinese martial adage: “A good fighter is a good doctor, and vice versa.” One martial arts article summarizes, “the same points used as acupuncture points for healing can, under certain conditions, also cause harm… In the past, a good martial artist was also a good doctor, following the ‘before learning to demolish, learn to fix’ dogma.” We see this wisdom reflected in Katara. By Book 3, she is essentially the team’s medic (healing Aang, Jet, and others) but also one of its most formidable fighters. She knows how to hurt (water whips, etc.) and how to heal – two sides of the same coin. In a sense, Katara carries on a Shaolin-like lineage: fight with compassion and only as necessary, heal whenever possible, and never use knowledge of the human body to inflict suffering unless absolutely forced. That last part becomes very relevant when we discuss bloodbending.

Water Tribe Culture: Parallels to Indigenous Arctic Peoples (and Hints of Chinese Influence)

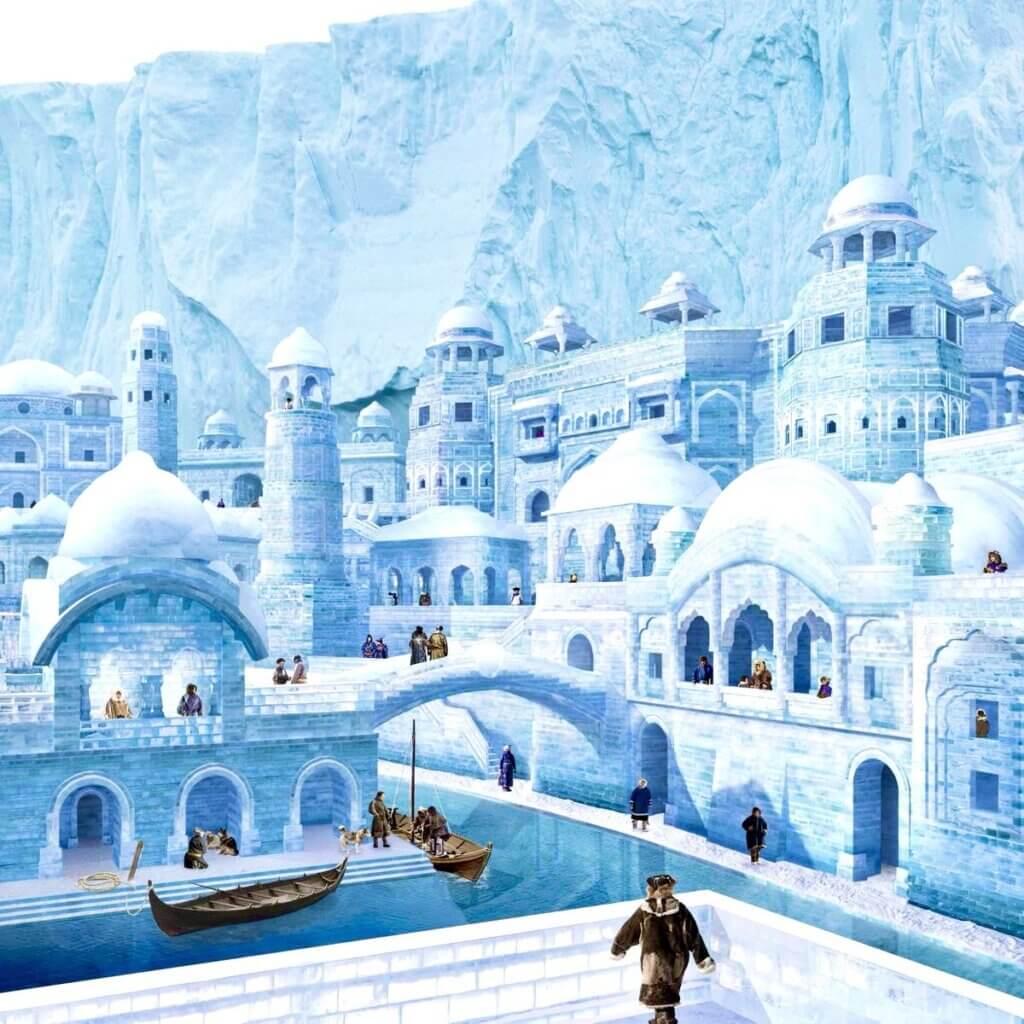

The Water Tribe is divided into the Northern and Southern Tribes at the poles, as well as the Foggy Swamp Tribe. Their culture, technology, and lifestyle draw clear inspiration from real-world Arctic and seafaring peoples – notably the Inuit/Yupik cultures of the far north. Like the Inuit, the Water Tribe builds with ice and snow (igloo-like structures and even a grand ice city), wears parkas and furs, travels via canoes and sleds, and relies on subsistence fishing and hunting of marine life. In Avatar, we see Sokka and Katara fishing for arctic seals, hunting for food, and navigating icy waters in canoes. This mirrors how indigenous Arctic communities survive on fishing, whaling, and sealing, making use of every part of the animal caught. The tight-knit kinship ties in the Water Tribe (e.g. Gran-Gran presiding over the Southern Tribe family group, arranged marriages in the Northern Tribe, etc.) also reflect the communal nature of Arctic tribes where cooperation and family are vital for survival in harsh climates. Each member of the community has a role – hunters, cooks, clothing-makers – just as Sokka is a hunter-protector and Katara initially a caretaker of the home in the Southern Tribe. Their reverence for the environment (thanking the Moon and Ocean for fish, respecting the balance of spirits) resonates with the spiritual beliefs of many indigenous peoples who honor animal spirits and cosmic forces.

One can draw parallels between the Water Tribe’s spiritual beliefs and those of various seafaring cultures. The Water Tribe worships Tui and La, the Moon Spirit and Ocean Spirit, acknowledging that “our strength comes from the Spirit of the Moon; our life comes from the Spirit of the Ocean”. This is strongly reminiscent of how ancient seafaring peoples would revere the moon (for its control of tides and its light at night) and the ocean (as a source of life and danger). For example, Inuit mythology has stories of the Moon deity (often male, who chases his sister the Sun across the sky) and a dominant Sea Goddess (Sedna) who rules the ocean’s bounty. Sedna must be kept appeased by shamans so she will release sea animals for the hunters. In ATLA, we see a similar idea: when the Moon Spirit (Tui) is killed by Zhao. Princess Yue sacrifices herself to become the new Moon Spirit, restoring balance – a mythic act that wouldn’t be out of place in an indigenous legend of a human transforming into a guardian spirit to save their people.

Interestingly, the Water Tribe’s spiritual concepts also have Chinese influences layered in. We mentioned Tui and La literally mean “Push” and “Pull” in Chinese, describing the tidal forces. Moreover, the imagery of the two koi fish circling each other in the Spirit Oasis is a direct visual of the Yin-Yang symbol (one fish is white with a black spot, the other black with a white spot, together forming a living Taijitu). The show creators deliberately invoked Yin and Yang, the ancient Chinese concept of dual, complementary forces that form a balanced whole. The Moon is traditionally Yin (feminine, soft, reflective) and the Ocean’s vast energy can be seen as Yang (masculine, active, forceful), yet each contains a bit of the other – just as Tui and La chase each other in an eternal dance. This philosophical depth gives Water Tribe beliefs a universality: they resonate with Chinese Taoist ideas of harmony and balance, while also echoing animistic traditions globally. In fact, Princess Yue’s name itself is the Chinese word for “Moon” (月, Yué). Her character design was inspired by the Chinese Moon Goddess, Chang’e, complete with pale hair and serene beauty.

So the Northern Water Tribe, though modeled on an Arctic culture, has a layer of East Asian influence in its spiritual life and aesthetics – likely a deliberate blend to make this fictional culture unique. For instance, the architecture of the Northern Water Tribe’s city, with its bridges, towers, and gates, has hints of East Asian design (curved roofs, possibly inspired by East Asian temples albeit made of ice). Their writing system in the show uses Chinese characters (like the rest of the world of Avatar) – the word “waterbending” on their scrolls is written as 截水神功, which roughly means “Divine Ability to Control Water” in Chinese. All these touches weave Chinese cultural elements into the Water Tribe tapestry.

Another parallel worth noting is navigation and the lunar calendar. Historically, many cultures relied on the moon and stars for navigation at sea. The Water Tribe, being seafarers (the Southern Tribe men are largely fishermen and later a Navy), would track the moon’s phases for tides and for when their bending is strongest. This aligns with the Chinese lunar calendar, where important dates are tied to moon phases. Traditional Chinese fishing communities, much like others, planned fishing trips around the tides and moon – certain phases yield better conditions for fishing or traveling. In Avatar, during a full moon, waterbenders reach the peak of their power, and during a lunar eclipse or new moon, they are at their weakest. This is explicitly shown during the siege of the North: when Zhao killed the Moon Spirit (equivalent to a permanent lunar eclipse), the waterbenders lost all their bending ability until the moon was restored. This reflects a belief that the heavenly bodies directly influence human affairs – a concept present in both Chinese thought (astrology, Feng Shui, etc.) and Inuit lore (where the moon’s moods could affect hunting).

The Water Tribe’s relationship with the ocean also has parallels in East Asian cultures like China’s coastal communities. In China, fishermen traditionally worshipped Mazu, the goddess of the sea, for protection – somewhat analogous to how Water Tribe culture venerates the Ocean Spirit (La) for giving them life and fish. While the Water Tribe is not a direct analog of any one culture, it’s an amalgam that feels familiar. The extreme climate survival aspects (building shelters from ice, fishing through holes in the ice, traveling by sled dogs or equivalents like polar bear-dogs) come straight from the Arctic peoples’ playbook. The communal igloo Katara and Sokka live in at the series start could be taken from an Inuit village scene. The gender roles initially shown – with men as hunters/warriors and women as home-makers (and in the North, women forbidden from combat bending, only allowed to heal) – also reflect some traditional gender divisions in indigenous societies (though notably, actual Inuit women were not forbidden to hunt or fight, that aspect may have been more a nod to historical East Asian norms). It creates an interesting dynamic where Katara has to break a sexist barrier in the North to learn water combat, similar to how real history has often seen women healers being accepted but women warriors facing prejudice. Eventually, the Northern Tribe evolves, likely thanks to Katara’s example, just as the world of Avatar progresses socially.

In summary, the Water Tribe culture grounds Avatar in a believable human tradition: they are survivors of frigid extremes with a rich spiritual life tied to the celestial and natural world. The Chinese influences – from language to philosophy – give them an added layer of depth that connects to the show’s broader Asian aesthetic. We as viewers subconsciously recognize these patterns, which makes the fantasy culture feel authentic and lived-in. When Aang and Katara tread on the crunchy snow of the Northern Water Tribe’s capital under the full moon, we feel like we’re glimpsing an ancient ceremony that could exist in some alternate Earth, perhaps in a myth about the circumpolar peoples who can command water and talk to the moon.

Gentle Tide and Raging Tsunami: The Dual Nature of Water (and Waterbenders)

Water is often called the source of life – it nurtures, heals, and sustains. Yet water can also be terrifyingly destructive – floods, storms, and tsunamis can wipe out entire settlements. This dual symbolism of water is keenly present in both real-world mythology and the world of Avatar. The show does not shy away from portraying water’s two faces: on one hand, we have healing water, sacred oasis ponds, cleansing rain, and the comforting presence of the moon’s reflection. On the other, we have frozen glaciers that can crush ships, water used as whips and blades in combat, and the horrifying concept of bloodbending, in which a waterbender can control the blood within another person, essentially puppeteering their body against their will.

In Chinese philosophy, the element of Water (水) encapsulates this paradox. It is the most yin, associated with stillness, wisdom, and softness – but it also holds latent power that can be unleashed in an instant. A Chinese text might note that “water can be fluid and weak, but can also wield great power when it floods and overwhelms the land.” In one moment water is a gentle, babbling brook; in another it’s a torrential flood. This is captured in Avatar visually and narratively. Katara’s character often represents water’s gentle, life-giving side. She’s a healer, a nurturer to her friends, and her bending style even in combat tends toward defensive, immobilizing moves rather than lethal strikes. She uses water to put out fires and to protect. Aang, too, being an Air Nomad at heart, uses water defensively when he learns it – like creating encasing bubbles or giant waves to push enemies away without hurting them outright.

However, when push comes to shove, water can become a weapon of immense destruction. The most dramatic example is at the end of Book 1: when the Moon Spirit is slain, Aang merges with the Ocean Spirit and becomes the colossal Koizilla – a glowing titan of water who devastates the Fire Nation fleet. In that state, water (empowered by the enraged Ocean Spirit) acts as a vengeful force of nature. It sweeps warships into splinters like an angry hurricane given form. The tranquil Spirit Oasis turns into a font of fury. This scene is essentially a tsunami personified, and it shows that even the usually peaceful Aang can become destructive when channeling water’s raw power (albeit under the Avatar State’s influence). Here, water’s duality is on full display: the same element that moments ago had been used for healing is then unleashed in devastation. It’s a startling contrast that reinforces the theme that balance is needed. Water’s destruction was provoked by human imbalance (Zhao killing Tui). Only by restoring balance (Yue becoming the new Moon) does the destruction halt.

The moral tension of using water’s destructive potential comes to a head with Bloodbending. Introduced in the episode “The Puppetmaster,” bloodbending is a forbidden technique pioneered by Hama, a Southern Tribe waterbender. By bending the water present in blood, a waterbender can physically control another person like a marionette, overriding their muscle control. This is, objectively, a terrifying ability – effectively it removes someone’s autonomy. Katara’s reaction upon learning it is horror and disgust. She considers it unnatural and immoral, using it only in the direst moments and later swearing never to rely on it again. Bloodbending forces the question: should those with power impose their will so directly on others? It’s analogous to debates in martial arts or warfare about honor and limits. In real martial traditions, there were often “forbidden techniques” – moves considered too brutal or dishonorable except in life-or-death scenarios (eye gouging, certain fatal strikes, etc.). Many martial arts have codes of conduct to prevent abuse of skills. In the Avatar world, bloodbending becomes outlawed (as seen in The Legend of Korra – Republic City has made its use a crime) because it violates the natural order and individual rights. This mirrors how societies might ban biological warfare or other extreme methods.

Interestingly, the mechanics of bloodbending resonate with Chinese martial folklore. There were legends of masters who could paralyze or kill with a touch to secret acupoints (the infamous Dim Mak or “death touch”). While often exaggerated, the kernel of truth is that pressure point strikes can indeed knock someone out or cause temporary paralysis by disrupting nerve signals – not unlike how bloodbending disrupts a bender’s chi or a person’s motor signals. Hama even uses bloodbending to block Katara from moving or bending, akin to a super-advanced chi-blocking. In Chinese wuxia stories, there are instances of evil masters who use their knowledge of qi to dominate others (for example, using poisons or spells to control a person’s will, or techniques to cause internal injury without outward sign). These were typically depicted as dark arts, to be used only by villains or in extreme need. Bloodbending fits that archetype as the “dark art” of waterbending. It’s the ultimate perversion of water’s purpose: instead of giving life, it seizes life and freedom. Katara’s hesitance to use it, and the remorse she shows when she does, highlight her moral compass. She chooses water’s healing, life-affirming path as her true way.

From a philosophical perspective, water’s duality also teaches a lesson: the strongest waterbenders (and characters) are those who can reconcile the gentle and the strong, wielding great power compassionately. Katara exemplifies this when she defeats Hama. She does bloodbend Hama to save Sokka and Aang, showing she’s capable of that ruthless edge, but she immediately rejects it after stopping the threat. Later in Book 3, Katara’s journey brings her face-to-face with the man who killed her mother. In that episode, she bloodbends the guards who stand in her way, a chilling reminder of the power she swore never to use. When she finally confronts the killer himself, the storm inside her nearly drives her to murder him with a massive attack of ice spears. But in the end, she pulls back — realizing that taking his life would poison her soul in a way she could never undo. Aang calls it “seeking vengeance” versus “seeking justice,” relating to how one uses power. Katara ultimately chooses to let her anger go, symbolically letting the rain (water from above) wash away her hatred. This is a very zen moment, aligning with Buddhist/Daoist ideas of not succumbing to one’s darker impulses.

Another dimension of water’s paradox is its association with emotion. Water is often linked to feelings, adaptability, and intuition. Katara (and waterbenders generally) wear their hearts on their sleeves more than, say, the stoic earthbenders or fiery firebenders. Katara’s emotional strength is a boon – her love fuels her healing, her grief for her mother drives her to protect others – but it can also lead to overwhelming surges (like that near vengeance).The moon, which governs water, is similarly tied to emotional cycles in human lore (think of terms like “lunatic” from lunar, or how full moons are said to heighten emotions). The show connects this subtly: waterbenders are strongest at full moon, which is when their emotions might also run high. Hama, for instance, was only able to bloodbend under the full moon, when its power gave her the strength to act on the bitterness she carried within her. So, maintaining inner balance is as important for a waterbender as controlling the external water. This resonates with Tai Chi’s teaching that internal harmony and calm yield the best martial results. In a sense, Katara’s true mastery of water came when she found balance between her compassion and her just fury – achieving the stillness of a calm sea that conceals great depth.

Finally, tying back to Wu Xing (Five Elements Theory): In that framework, water corresponds to winter, a season of stillness, conservation, and restoration (fittingly, the majority of waterbenders live in lands of ‘perpetual winter’). It is the phase where life energy (yang) withdraws and yin dominates – a time to rebuild strength for the burst of spring. Waterbenders indeed draw power from the night (a yin time) and especially in the winter months (more water, longer nights – we even hear that more waterbenders are born in winter months, which is a fun nod to astrology). Moreover, water overcomes fire in both Wu Xing and Avatar. Water’s role in the conquest cycle is to extinguish fire, which is fittingly portrayed: the Fire Nation’s might is ultimately foiled by water (first at the Northern Water Tribe by the ocean’s fury, later in the final battle where Katara defeats Azula and Aang defeats Ozai with all the elements—including water). Conversely, earth (dams, canals) can stop water. These elemental relationships add a layer of rich logic to the bending world, borrowed from Chinese cosmology.

In conclusion, waterbenders embody a balance of gentle mercy and formidable strength. Like the element they bend, they are healers, nurturers, and diplomats at heart, but when pushed to extremes, they can unleash unimaginable power. The key is balance – between push and pull, between soft and hard, between the healer’s touch and the warrior’s strike. Katara and her fellows illustrate that true strength in waterbending (as in life) comes from knowing when to yield and when to assert, when to heal and when to fight. The real-world philosophies and martial arts behind waterbending all teach this same lesson. Tai Chi masters, acupuncturists, and wise generals alike understand the dual nature of life energy. Waterbenders are simply students of that ancient wisdom, wearing the mantle of the moon and ocean as they keep balance in their world.

Conclusion: Between Academic and Mythic – The Legacy of Waterbending

Waterbending in Avatar: The Last Airbender is a shining example of the series’ thoughtful world-building – every move and concept has roots in real human tradition, especially the rich heritage of Chinese martial arts and philosophy. We’ve seen how Tai Chi provides the choreography and mindset for waterbenders: their fluid motions, breathing, and redirection tactics come straight from that art, teaching the power of softness and flow. We’ve explored how qi and meridians underlie the Water Tribe’s healing, connecting Katara’s miraculous cures to the principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine and martial arts pressure points. We’ve drawn lines from Sun Tzu’s ancient maxims to the strategic cunning of Sokka and the adaptive fighting style of waterbenders in battle. We’ve journeyed to the poles to compare the Water Tribe’s lifestyle with real Arctic peoples – finding both obvious parallels in survival techniques and subtle influences from Chinese language and spirituality (Push and Pull, Yin and Yang, the very name Yue). Waterbending’s story is as much one of culture and ethics as of combat: it poses questions of how to use great power responsibly, embodied in the emotionally charged issue of bloodbending and the role of a warrior-healer. And it situates itself in a cosmic framework where the moon’s cycle and the five elements theory inform the ebb and flow of power.

For a fantasy aimed at a broad audience, Avatar deftly operates on multiple levels. A child can be awe-struck by the cool water-whip moves and understand the simple moral that “water is good for healing and defense, but can be dangerous if misused.” An adult, meanwhile, can appreciate the almost scholarly detail – noticing Tai Chi postures, smiling at the push-pull names of the spirits, and recognizing themes from Chinese philosophy about balance and harmony. The tone of this exploration has tried to mirror that blend: at times academic (pointing out sources and philosophies) and at times like a casual fan enthusing over how “awesome and meaningful” waterbending is.

In the end, Waterbending’s real-world ties centered around China (and other cultures) deepen our appreciation for the art. It reminds us that fantasy often draws from the well of human knowledge. When Katara stands in her waterbending stance under the full moon, palms circling gracefully as water rises at her command, she is participating in a tradition that could be at home in a Tai Chi courtyard at dawn, or in the hut of a village healer, or in the pages of Sun Tzu – all refashioned in a new myth for a new generation. The philosophy of water – to be adaptable, to heal, and to know when to unleash overwhelming force – is timeless. Uncle Iroh said it simply in the show: “Water is the element of change.” The Waterbenders change themselves and others, not through brute strength, but through understanding the true nature of energy. In doing so, they, like water, find a way to shape the world while remaining in harmony with it. And that is a lesson as profound as any martial arts scripture or medical textbook – one that bridges the worlds of fiction and reality, East and West, child and adult.

Avatar: Bending Styles & Weapons

Interested to learn more about “Avatar: The Last Airbender”? Check out our article “The Exact Martial Arts Styles Behind Avatar: The Last Airbender Bending” to learn about the Chinese Martial Arts Styles, Weapons, and Philosophy within the show!