Table of Contents

- The Essence of Earthbending and the Earth Kingdom’s Philosophy

- The Earth Kingdom: Influences from Imperial China and Beyond

- Legends, Lineage, and the Roots of Earthbending

- Hung Gar & Southern Mantis: The Real Martial Arts Behind Earthbending

- Non-Bending Warriors of the Earth Kingdom: The Kyoshi Warriors and More

- The Legacy of Earthbending: From Fantasy to Reality

Introduction

Avatar’s Earthbenders are renowned for their raw strength, steadfast resolve, and deep connection to the ground beneath them. In the world of Avatar: The Last Airbender (ATLA) and its sequel The Legend of Korra, Earthbending is much more than hurling rocks around – it’s an art form rooted in real martial arts and enriched by diverse historical influences. From the strong stances of Hung Gar kung fu to the imperial grandeur of the Earth Kingdom’s cities, Earthbending draws inspiration from our own world’s fighting styles and cultures. This friendly deep-dive will explore the essence of Earthbending, the real-life martial arts behind it, the cultural and historical lore of the Earth Kingdom, and even the formidable non-bending warriors who call this nation home. Let’s dig in (pun intended) to discover how Earthbending bridges fantasy and reality!

Spoiler Warning:

This article may contain detailed discussion of storylines, characters, and lore from Avatar: The Last Airbender, The Legend of Korra, and minor points related to the comics and novels. If you haven’t finished the series and wish to avoid spoilers, we recommend returning to this piece after watching both shows.

Earth.

“There’s no different angle, no clever solution, no trickety-trick that’s going to move that rock. You’ve got to face it head on.”

-Toph Beifong

The Essence of Earthbending and the Earth Kingdom’s Philosophy

Earthbending is all about substance, stability, and strength. Unlike the light-footed Air Nomads or fluid Water Tribe, an Earthbender’s ideal mindset is to stand their ground and “wait and listen” before striking. In ATLA, King Bumi (the eccentric Earth King of Omashu) taught Aang about a principle called neutral jing – essentially the art of doing nothing until the opportune moment. Neutral jing is the key to Earthbending, emphasizing listening and patience; an Earthbender absorbs or endures an oncoming attack and only counters when they feel the time is right. Bumi himself demonstrated this during the war: instead of fighting a losing battle, he surrendered his city to the Fire Nation and bided his time as a prisoner. Later, during the solar eclipse when firebenders were powerless, Bumi broke himself out and easily liberated Omashu – perfect timing!. This tactical patience and steadfastness lie at the heart of Earthbending philosophy.

Physically, Earthbenders are often rooted and immovable until they choose not to be. Their style balances offense and defense in equal measure: they can brace behind a stone wall one moment and launch a boulder the next. As Iroh noted in the show, “Water is soft and yielding, but Earth is firm and decisive.” True to that, Earthbending maintains a distinct equilibrium between strength and defense, using solid stances to absorb attacks and overpower foes with sheer force when the chance comes. Even Aang, a naturally air-aligned person, had to learn to “face things head-on” (as his Earthbending teacher Toph phrased it) and adopt a more grounded, stubborn attitude to master Earthbending. The element of Earth rewards bravery, fortitude, and a bit of ornery stubbornness – traits embodied by famous Earthbenders from the gentle giant Bumi to the indomitable Toph Beifong.

The Earth Kingdom: Influences from Imperial China and Beyond

The Earth Kingdom – home of the Earthbenders – is the largest and arguably most culturally rich of the Four Nations. Its cities, clothing, and customs are heavily inspired by real East Asian civilizations, primarily Imperial China. If the Water Tribes echo the Arctic Inuit and the Fire Nation channels Imperial Japan, the Earth Kingdom unmistakably wears the heritage of monarchical China on its sleeve. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the magnificent capital, Ba Sing Se.

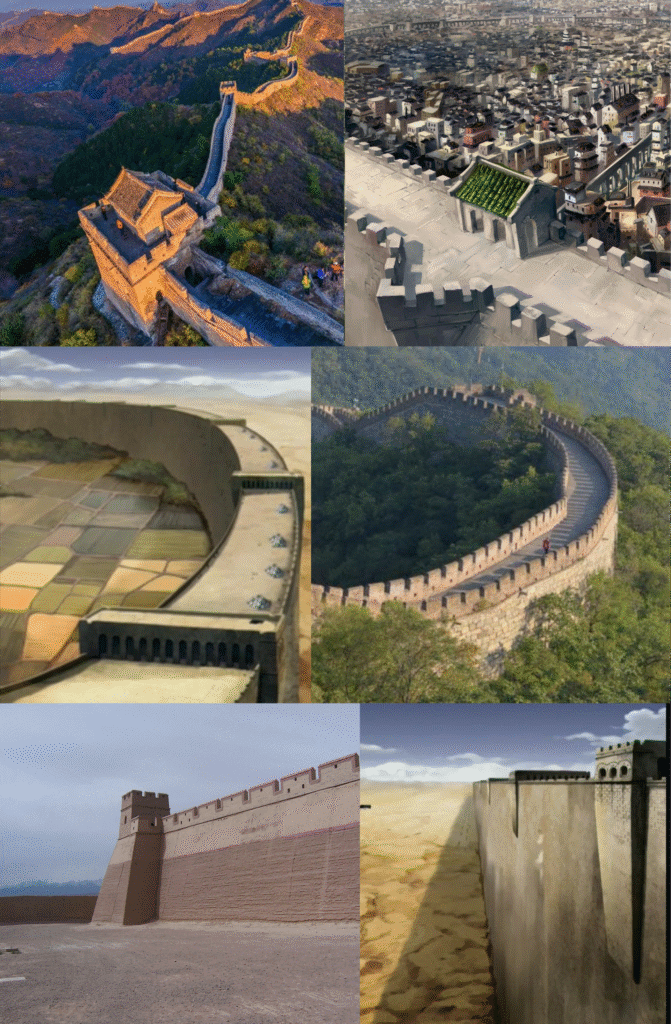

Ba Sing Se in the series is a vast walled metropolis – and it directly parallels historical Beijing and other Chinese imperial cities. The very name “Ba Sing Se” means “Impenetrable City” in Chinese, and the city’s most famous feature is its gigantic outer wall (dubbed the “Great Wall of Ba Sing Se”), which is a clear allusion to the Great Wall of China. Inside the city, the royal palace sits behind multiple rings of walls, much like the Forbidden City in Beijing which was a palace complex protected by concentric walls. In fact, the upper-class architecture of Ba Sing Se – with its sweeping roofs and grand gates – unmistakably resembles the Forbidden City’s iconic design. There’s even a regal palace entrance in Ba Sing Se that mirrors the Meridian Gate of the Forbidden City.

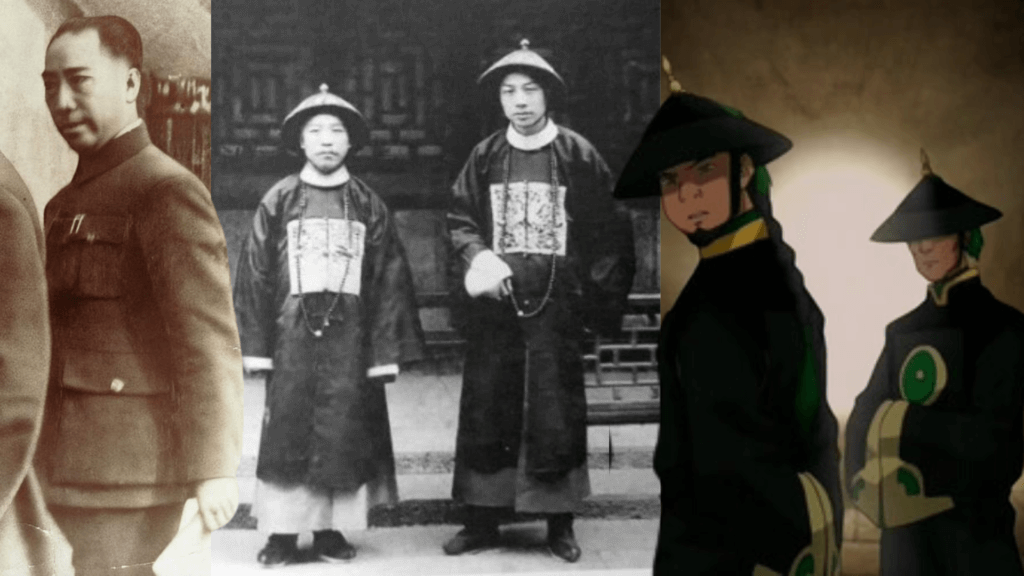

Culturally, Ba Sing Se during the reign of Earth King Kuei draws from the Qing Dynasty era of China (17th–19th century). For example, the men of Ba Sing Se are shown wearing their hair in a long braided queue with a shaved forehead – the mandatory hairstyle for men under Qing rule. You’ll also spot topknots on many Earth Kingdom men (typically outside of the capital city), a hairstyle historically mandatory for men in pre-20th-century China. Upper-class women in the Earth Kingdom’s capital are depicted with ornate headpieces similar to the liángbātóu headpiece popular among Manchu noblewomen of the Qing Dynasty. These details, from fashion to fortifications, firmly root the Earth Kingdom in a Chinese aesthetic. The show even uses Chinese characters in Earth Kingdom writing and signage. It’s a loving tribute to Chinese culture, making the fantasy Earth Kingdom feel like a lost chapter of real history.

That said, the Earth Kingdom is huge and diverse, and Avatar sprinkled in influences from other cultures as well. For instance, in one episode Zuko and Iroh hide in a poor Earth Kingdom village where they meet a young woman named Song. Both Song and her mother wear traditional Korean hanbok dresses, and the village architecture has a Korean style – showing that some Earth Kingdom provinces were inspired by Korea. Meanwhile, the far-flung Kyoshi Island has a decidedly Japanese flair. Kyoshi Islanders, though technically Earth Kingdom citizens, have their own customs and look. The Kyoshi Warrior uniforms include samurai-like armor and katana swords, making them one of the few groups in ATLA based on Japanese culture. The Kyoshi Warriors’ iconic metal fans are directly inspired by tessenjutsu, the Japanese martial art of the war fan. Even their face makeup – white with bold red and black patterns – evokes Japanese kabuki theater or the facepaint of geisha entertainers. This is a cool nod, since Avatar Kyoshi (who founded the island’s traditions) was herself an Earth Kingdom Avatar but is portrayed with a mix of Chinese and Japanese elements.

The cuisine is largely Chinese-inspired as well – remember the roast duck that King Kuei’s pet bear Bosco loved? Dishes like roast duck and “jook” (rice porridge) are straight from Chinese cuisine. The show even slyly references this: when Bosco has a birthday feast in the comics, the spread is basically Chinese banquet food (from red-braised pork to pickled ginger). And of course, tea is practically a cultural institution – Uncle Iroh’s beloved jasmine tea reflects how tea drinking began in China and became a national pastime. The Earth Kingdom is so vast that it contains multitudes – just as China has 56 ethnic groups and varied regional cultures, the Earth Kingdom has diversity too. We encounter isolated villages, giant metropolis cities, desert tribes, and mountain settlements, each with their own flavors.

Yet, across this diversity, one thing is common: the Earth Kingdom’s people share an unshakable spirit. They endured a century of war against the Fire Nation, often against terrible odds. Even when cities fell (Omashu was occupied; villages were conquered), many Earth Kingdom citizens kept fighting in guerrilla resistance (like Jet’s freedom fighters or the various rebel groups). Ba Sing Se famously withstood a massive Fire Nation siege for 600 days, never letting the enemy break its walls. That stout defiance – “we will not be moved” – is emblematic of earthbending’s spirit. It calls to mind China’s own history of resistance against invasion, such as during the Japanese invasions in the 1930s. In fact, the entire Hundred Year War in Avatar, with the Fire Nation (an industrialized island power) attacking the Earth Kingdom, parallels the conflict between Imperial Japan and China in the late 19th/early 20th century. The Fire Nation wields advanced technology and industry (like Japan post-Meiji Restoration), while the Earth Kingdom, much like Qing Dynasty China, struggles with internal politics and slower industrial progress. This real-world parallel adds depth: Earthbenders’ stubborn resistance in the show echoes the tenacity of a real nation fighting to preserve its sovereignty and culture.

In addition to mirroring real-world conflicts, the very political structure of the Earth Kingdom also mirrors history. In ATLA, the Earth Kingdom is ruled by a King from Ba Sing Se, but by Aang’s time the central monarchy had become mostly a figurehead. Real power in the capital was wielded by the Dai Li, the shadowy secret police who controlled information and maintained order behind the scenes. This setup strongly resembles the situation in late Qing Dynasty China, where the young Emperor Guangxu was technically the ruler but the true authority was held by Empress Dowager Cixi from behind the throne. In Avatar, Earth King Kuei is kind and well-meaning but naïve, manipulated by his advisor Long Feng (leader of the Dai Li). Likewise, Emperor Guangxu’s decisions were overridden by Cixi, who effectively ran the empire. The parallel is deliberate – it’s one more way the Earth Kingdom reflects historical China’s power dynamics.

Even the name “Dai Li” has a historical Easter egg: the Dai Li are named after a real person, General Dai Li, who was the feared head of the secret police in 1940s China. The real Dai Li led Chiang Kai-shek’s intelligence agency and had a reputation for ruthlessness, quite like his fictional counterparts. In fact, General Dai Li was sometimes called “the Chinese Himmler” for his oppressive tactics, and the Avatar creators chose his name for Ba Sing Se’s cultural enforcers as a sly reference. The Avatar Dai Li agents even wear broad conical hats as part of their uniform, and interestingly, the Chinese characters for “Dai Li” (戴笠) literally translate to “wearing a bamboo hat” – a fun coincidence that the show writers surely noticed!

Beyond China and Japan, the Earth Kingdom takes inspiration from across East Asia and even parts of Central Asia. The show’s art book notes that the city of Gaoling (Toph’s hometown) has a vibe reminiscent of China’s Tang Dynasty. Some Earth Kingdom commoners (like the girl Song) wear Korean-style clothing. The Kingdom’s vast geography includes a great desert (the Si Wong Desert) analogous to the Gobi Desert, and just as in Chinese history, nomadic tribes live on its frontiers. The nomads (like the sandbender tribes) are viewed by the Earth Kingdom much as imperial China viewed steppe nomads – as barbarians on the fringe. We even see outfits and customs among desert folk that hint at Mongol or Central Asian influence (fur hats, yurts, etc.). All these touches make the Earth Kingdom feel real and lived-in, with regional variation just like a real country.

In short, the Earth Kingdom is a colorful patchwork of cultures, unified by Earthbending but enriched by many real-world traditions. This attention to cultural detail is part of why ATLA’s worldbuilding is so immersive. Whether it’s Ba Sing Se’s Ming/Qing Dynasty splendor or Kyoshi Island’s samurai spirit, the influences are clear and make the Earth Kingdom a loving homage to Asian history.

Legends, Lineage, and the Roots of Earthbending

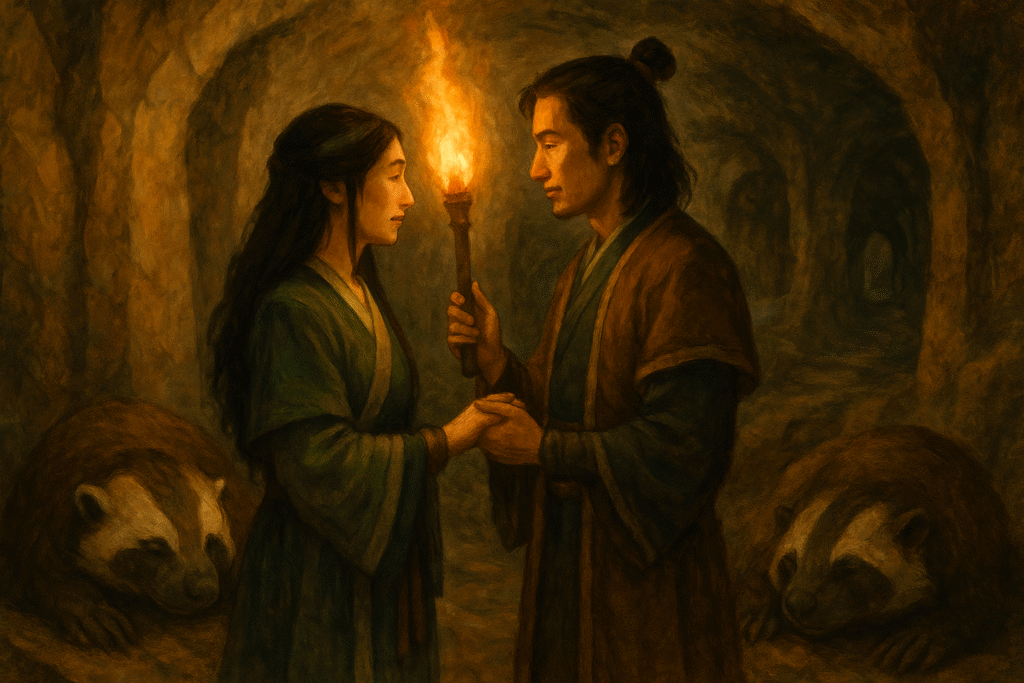

Every bending art in Avatar: The Last Airbender has mythical beginnings, and Earthbending is no exception. The most famous earthbending legend passed down from that time is “The Legend of the Two Lovers,” which ATLA fans will recall from the Cave of Two Lovers episode (yes, the one with the secret tunnel song!). The story tells of Oma and Shu, two lovers from rival villages separated by a mountain and a war. Meeting in secret, they learned Earthbending from the badgermoles — massive, blind creatures who navigate the underground with seismic sense. The lovers carved a network of tunnels within the mountain so they could meet in safety, a place that became known as the Cave of Two Lovers.

One day, Shu did not appear. He had been killed in the fighting. Stricken with grief and anger, Oma emerged from the mountain and revealed her Earthbending to both sides, demonstrating overwhelming power to end the bloodshed. The two villages united, founding a city named Omashu in their honor. The legend, still told in the Earth Kingdom, is not just a romantic tragedy — it is an origin myth that ties the beginnings of human Earthbending to the founding of one of the Earth Kingdom’s greatest cities.

This blending of personal story, martial skill, and civic origin has deep roots in real-world history. Across Asia, myth often serves as cultural legitimacy — the foundation on which authority and identity are built. In Imperial China, emperors linked their rule to ancient legends like that of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi), a mythical sovereign said to have invented weapons and military strategy after observing animals and the natural world. By rooting political power in myth, rulers could present their reign as part of an unbroken lineage reaching back to the dawn of civilization. In Avatar, Omashu’s founding through Oma and Shu functions in the same way — its political importance is bolstered by a romanticized, almost sacred origin.

The badgermole connection is another echo of Chinese tradition. In Chinese martial culture, some of the most famous styles are animal-inspired, modeled after the movements, attitudes, and strengths of creatures such as the Tiger, Crane, Snake, Leopard, and Dragon. These styles are not only physical imitations but also philosophical — the Tiger represents power and rooted stability, the Crane embodies balance and grace, the Snake teaches flexibility and precision. In Earthbending, the badgermole’s tunneling and seismic awareness translate into low stances, grounded movements, and the ability to “feel” the terrain, mirroring how real martial artists draw inspiration from an animal’s strengths and natural environment.

The themes of love, war, and the founding of cities also have real-world parallels across Asia. Folklore often turns personal sacrifice into collective identity. Chinese opera contains many tragic romances, such as The Butterfly Lovers, where the fate of two lovers becomes symbolic of loyalty, resistance, and transformation. In Vietnam, the legend of Lạc Long Quân and Âu Cơ explains the origin of the Vietnamese people through a union between two different worlds. These stories endure because they merge human emotion with the birth of something greater — a city, a culture, a people. In that sense, Oma and Shu’s tale is less a fantasy invention and more a continuation of a long tradition of tying love and loss to the formation of communities.

There’s also a martial dimension to Oma’s role in ending the war. In both Wuxia literature and historical accounts, martial skill is not only a means to victory but a path to peace. The best warriors are remembered not just for their power, but for the wisdom to use it decisively and morally. Yue Fei, the Song Dynasty general, is still celebrated not only as a brilliant tactician but as a paragon of loyalty and virtue. Oma’s decisive Earthbending mirrors this archetype: she did not use her strength to dominate, but to end the conflict entirely. The message is that true mastery involves knowing when to stand firm, when to yield, and when to act with finality.

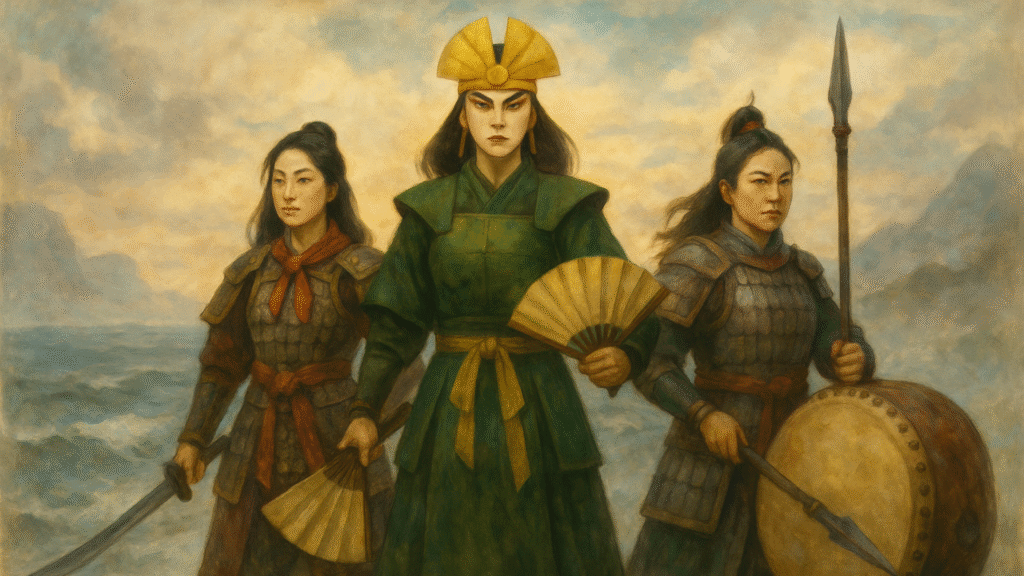

If Oma and Shu are Earthbending’s mythic parents, Avatar Kyoshi is its legendary champion. She stands in history much like a founding martial ruler in the real world — a figure who defines borders, shapes national identity, and leaves a warrior legacy. Towering, implacable, and utterly decisive, she is remembered for the singular act that defined her homeland’s future: splitting it from the mainland with her Earthbending to form Kyoshi Island. This was no mere display of strength. By physically severing the land and surrounding it with water, she created a natural barrier against invasion, ensuring her people’s safety for centuries.

This motif — the legendary founder reshaping geography — is a familiar thread in East Asian lore. Chinese myth credits Yu the Great with “taming the floods” and reshaping rivers to save early settlements. Daoist legend tells of immortals like Lü Dongbin cleaving mountains to create new passageways. In Korea, the walls of Hanyang Fortress were raised to hug the city’s mountains, using nature as part of defense. Across the region, leaders who could mold the landscape were not just problem-solvers; they were nation-builders. Defining physical borders was, and remains, a powerful political statement — an act of autonomy that declares, “Here is where we stand.”

Kyoshi’s legacy was not only geological but martial. As both Avatar and political leader, she founded the Kyoshi Warriors, an elite all-female fighting force sworn to defend the island’s independence. This union of governance and martial prowess mirrors the rise of many historical dynasties founded by military leaders. Zhu Yuanzhang, the peasant-turned-monk who became the Ming dynasty’s first emperor, is one such figure — his reign supported by elite guards like the Jinyiwei, whose loyalty was to him alone. In Japan, samurai clans served a similar dual role as protectors and local rulers, preserving martial codes alongside political control. The Kyoshi Warriors, with their disciplined training, distinct armor, and ceremonial war fans, are spiritual kin to these historical orders: more than soldiers, they are living embodiments of their people’s identity.

The choice to make the Kyoshi Warriors an all-female unit also resonates with East Asian traditions of honoring women warriors. Chinese folklore immortalizes Hua Mulan’s courage and Liang Hongyu’s strategic brilliance in the Song dynasty, while the Yang family legends celebrate a lineage of women generals defending their clan. These figures, like Kyoshi herself, are remembered not only for their martial skill but for embodying virtues like loyalty, righteousness, and the fierce protection of home. Kyoshi’s towering presence and unyielding will fit seamlessly into this archetype — the warrior whose very image becomes a rallying banner.

Over time, Kyoshi’s legend took on an almost supernatural aura. In the Avatar canon, she lived to be 230 years old, making her a living monument whose influence spanned generations. This longevity has real-world parallels in the cult of the hero and the reverence of long-lived figures in East Asian culture. In Daoist tradition, immortals are said to walk among mortals for centuries, offering guidance and shaping events behind the scenes. In history, the lifespans of rulers and generals sometimes grew in the retelling, each new account magnifying their strength, wisdom, and moral authority. Kyoshi’s mythic lifespan, like her feats of Earthbending, elevates her from historical figure to enduring symbol — a reminder that her will, like the island she created, was immovable.

Kyoshi’s story, much like that of Oma and Shu, blends personal conviction, martial mastery, and political legacy into one. But while Oma’s act was born of love and loss, Kyoshi’s was a calculated move for the long-term security of her people. Both legends share the same cultural DNA: they root leadership in decisive action, link identity to land, and preserve their founders’ values in both story and stone. In the real world, these are the kinds of acts that become the foundation of nations — and in Avatar, they are what make Kyoshi’s name ring down the centuries.

Hung Gar & Southern Mantis: The Real Martial Arts Behind Earthbending

One reason the bending arts in Avatar feel so authentic is that the creators based each style on real-world martial arts. Earthbending’s primary fighting style is inspired by Hung Gar kung fu, a Southern Chinese martial art known for its deep stances and powerful strikes. Hung Gar (洪家拳, “Hung Family Fist”) originated in the 17th century and was famously practiced by folk heroes like Wong Fei-Hung (who appears in many Hong Kong films). In fact, the show’s martial arts consultant Sifu Kisu chose Hung Gar specifically because its ethos matches earth’s qualities.

Both earthbending and Hung Gar emphasize heavily rooted stances and powerful punches and kicks that evoke the mass and power of earth. Picture an earthbender planting her feet wide and low before driving a fist forward to launch a boulder – that solid base and forceful strike come straight from Hung Gar training. Practitioners of Hung Gar spend countless hours in mǎbù (horse stance), building leg strength and stability. In fact, Hung Gar fighters are famed for holding deep horse stances for extraordinary lengths of time to develop “legs of iron.” It’s no wonder Toph demanded Aang assume a horse stance to stop a rock; in Hung Gar, a low stance is literally the foundation of your power.

Another hallmark of Hung Gar is its use of animal-inspired techniques, especially the Tiger and the Crane, as referenced in the section above. The Tiger represents hard, ferocious power – clawing, strong stances, aggressive strikes – whereas the Crane represents soft power – grace, balance, and deflection. In Hung Gar forms, practitioners blend these into a seamless style (one famous set is even called “Tiger and Crane Double Form”). This blend of force and balance makes Hung Gar a perfect real-life parallel to bending rocks and soil. Earthbenders mostly display the tiger’s hard power: when Toph or Bumi hits, they hit like a tiger pouncing, with full force. But they can also show the crane’s soft resilience: standing firm and redirecting energy when needed, or landing lightly after a seismic move. As Avatar Wiki notes, “Hung Gar parallels animal movements such as the tiger’s hard blows and the crane’s affinity to landing gracefully on the earth.” In practical terms, an earthbender might use a hard tiger-like stomp to split the ground, then a soft crane-like shift to let an opponent’s attack glide by harmlessly. This balance of power and finesse is at the heart of Hung Gar – and earthbending.

One can’t talk about Hung Gar without mentioning its emphasis on strength and conditioning – which brings us to the idea of the “Iron Body.” In Chinese martial arts, especially southern styles, training often includes toughening the body to withstand impact. There’s the legendary “Iron Shirt” qigong, where masters condition their torso to resist strikes or even breaking objects on their body. Hung Gar has a set called Tid Sin Kuen (Iron Wire Fist) that uses dynamic tension and breathing to cultivate internal power and fortify the body. In some lineages, students wear iron rings on their arms during practice to strengthen their bridge (forearms) – a very earthy way to train, using literal metal weight. Earthbenders, likewise, exhibit a kind of iron body toughness. They’re typically muscular, stout and can trade blows with the best. Think of earthbending generals like General Fong who took a direct hit or the dauntless earthbender wrestlers in Toph’s Earth Rumble tournament – they pride themselves on being able to take a hit as much as give one. We even see Toph and other earthbenders breaking rocks with their bare hands or drilling their fingers into earth – feats that mirror real kung fu demonstrations where masters break bricks, stone slabs, or strike hard objects as conditioning.

Toph’s unique style deserves special mention. Unlike the standard Earth Kingdom earthbending method (taught in organized training huts or by the Dai Li), Toph developed her own way of fighting. Appropriately, the creators gave her a distinct real-world martial art: Southern Praying Mantis style (Chow Gar). This choice reflects Toph’s personality and circumstances. She is small, quick, and blind, relying on her seismic sense (vibration sensing) to “see.” Southern Praying Mantis is a close-range kung fu style that emphasizes rapid strikes, precise footwork, and keeping in contact with your opponent – it was considered ideal for a blind fighter who only needs one touch to read her enemy. Sifu Manuel Rodriguez, a practitioner of this rare style, even served as the motion model for Toph’s movements in the show.

Southern Praying Mantis is very different from the big, bold moves of Hung Gar. One martial arts writer described Chow Gar Mantis as having a “bizarre rhythm and unconventional movements,” even comparing it to a “fighting style of the undead” because of its jerky, unexpected motions. It’s an internal style, emphasizing sensitivity and using the opponent’s strength against them, rather than purely external muscle power. Masters of this style practice listening to energy through contact and responding with rapid-fire strikes. Interestingly, this echoes a concept called “sticky hands” in certain Chinese martial arts (like Wing Chun), where fighters keep a physical touch on their opponent to sense incoming attacks. Toph simply extends that idea to touching the ground – her feet and fingertips reading vibrations in the earth – to anticipate moves without sight.

Compared to Hung Gar, Toph’s stance is lower and her hands are held out loosely, feeling the ground, much like a mantis insect probing its surroundings. She displays bent elbows and a compact guard, rapid strikes in succession without pulling back, and an array of close-range hand techniques like slicing chops, finger jabs, clawing grabs, and elbow strikes. By using Chow Gar Mantis, Toph stays light on her feet but maintains constant contact with the earth – and crucially, she almost never kicks high. In fact, Chu Gar Mantis has virtually no high kicks; it stays low to the ground. This is perfect for Toph, who must keep her feet on the earth to “see”. It’s a brilliant blend of fantasy and real technique.

Beyond Hung Gar and Praying Mantis, Earthbending in Avatar incorporates other elements of Nanquan (Southern Fist) Chinese martial arts. Styles like Choy Li Fut, Lau Gar, and even the concept of “neutral jing” itself are drawn from these traditions. Neutral jing, as discussed, aligns with the idea of yielding and waiting found in arts like Tai Chi or certain Shaolin animal styles. The creators truly paid attention to martial arts detail: the result is that every punch, stomp, and block Earthbenders perform feels grounded (no pun intended) in authentic fighting principles.

Non-Bending Warriors of the Earth Kingdom: The Kyoshi Warriors and More

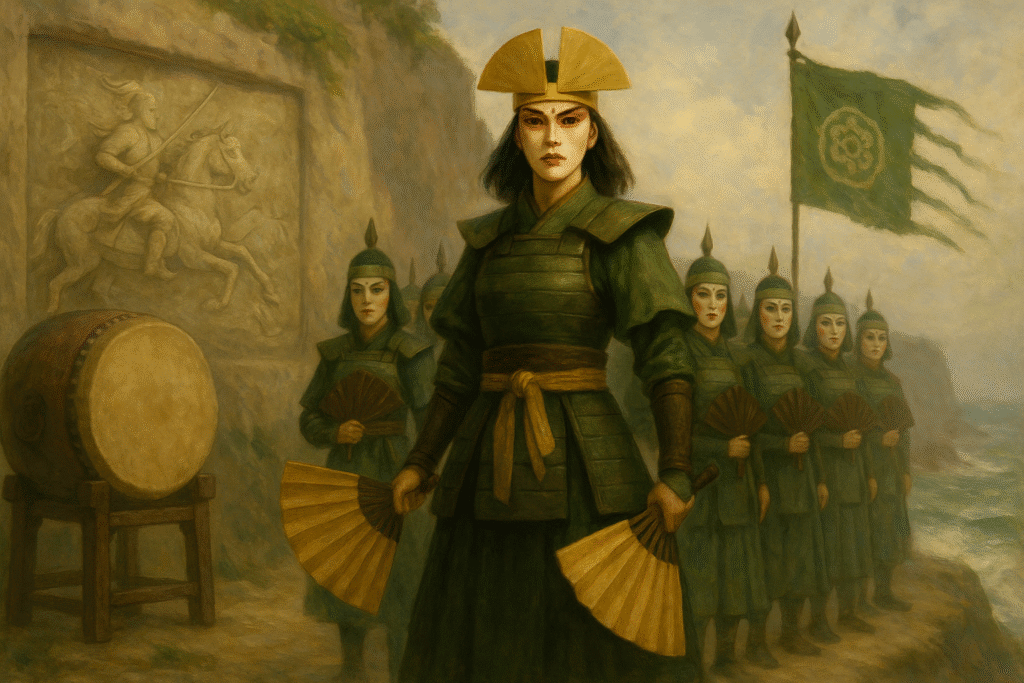

Not all heroes of the Earth Kingdom can bend earth – nor do they need to! The Earth Kingdom has its share of formidable non-bending warriors, who rely on traditional weapons and martial skills. Leading this group in fame (and face paint) are the Kyoshi Warriors. Founded in honor of Avatar Kyoshi, the Kyoshi Warriors are an elite band of all-female fighters who protect Kyoshi Island and, when called upon, serve the greater good of the kingdom. They prove that you don’t need to move mountains literally to be an earth-strength fighter.

The Kyoshi Warriors’ fighting style and attire are steeped in cultural influence. Dressed in emerald green armored robes with white face makeup and fierce red eye markings, they cut an imposing figure. Their primary weapons are metal fans, complemented by swords (often katana) and retractable shields. This loadout is directly inspired by the samurai of feudal Japan, making the Kyoshi Warriors a unique blend of Earth Kingdom loyalty with Japanese-style training.

In fact, as noted earlier, their use of war fans mirrors the art of Tessenjutsu. A fan might not seem deadly, but in skilled hands it can disarm, distract, and even cut. Suki, the leader of the Kyoshi Warriors in ATLA, demonstrates this by deflecting arrows and delivering swift takedowns with her iron fans. The Kyoshi Warriors’ makeup, as mentioned, resembles geisha and kabuki theater styles, possibly to strike fear and honor Kyoshi’s iconic look. They even wear topknot wigs crowned with a brass piece that resembles the headdress Kyoshi wore. All these touches tie the warriors to their namesake Avatar and give them a distinct identity among Earth Kingdom forces.

In terms of martial arts, the Kyoshi Warriors practice a style that emphasizes precision, agility, and disabling opponents quickly. They are experts at fighting benders despite not bending themselves. In one memorable encounter, a team of Kyoshi Warriors (led by Suki) managed to hold their own against the formidable Azula, Mai, and Ty Lee. What’s interesting is that Ty Lee, a non-bending acrobat from the Fire Nation, later joined the Kyoshi Warriors and brought her special skill: chi-blocking.

Chi-blocking is a technique where one strikes key pressure points on a bender’s body to temporarily paralyze their limbs or disrupt their chi flow, rendering them unable to bend. Ty Lee used this to great effect against the Gaang in ATLA (remember her jabbing Katara and making her arms go numb?). After the war, Ty Lee was so impressed by the camaraderie of the Kyoshi Warriors (whom she had fought against earlier) that she became an honorary member. She in turn taught the Kyoshi Warriors the art of chi-blocking, giving them an incredible edge in combat against benders. Thanks to Ty Lee’s lessons, Suki and her warriors could take down benders by targeting nerves – leveling the playing field between non-bender and bender. By the time of Korra’s era, chi-blocking techniques (originating from Ty Lee’s teachings) had spread widely; even the Equalists in Republic City used chi-blocking against benders. And it all traces back to the Kyoshi Warriors being open-minded enough to learn from a former enemy.

Beyond the Kyoshi Warriors, the Earth Kingdom has other notable non-bender fighters. There’s Jet and the Freedom Fighters, a band of Earth Kingdom orphans who fought against the Fire Nation using guerrilla tactics (hooks swords, smarts, and sheer nerve – though Jet’s methods were questionable). While not a formal martial arts school, Jet’s group showed the scrappy side of Earth Kingdom resistance. In Legend of Korra, we meet the Air Acolytes and Zaofu’s guards – though many of Zaofu’s security are metalbenders, some members of the Beifong household (like twins Wei and Wing) use a hybrid of acrobatics and mechanized suits, blurring the line between bending and technology. And of course, the ordinary Earth Kingdom army is filled with non-bender troops as well, armed with swords, spears, and even tanks in later years. They might not get the limelight, but they form the backbone of the Earth Kingdom’s defense, especially given (fun fact) the Earth Kingdom actually had the smallest percentage of benders among its population of all four nations. That means a lot of Earth Kingdom citizens had to rely on traditional combat training.

Still, the quintessential Earth Kingdom non-bending warriors will always be the Kyoshi Warriors. They uphold Kyoshi’s ideals of honor and protection, and they’ve proven themselves time and again. In the comics, they even become bodyguards for Zuko (the Fire Lord) to atone for the Fire Nation’s past, showing how skilled and respected they are. The Kyoshi Warriors demonstrate that the spirit of Earth – unwavering and brave – lives in anyone who trains hard and stands their ground, bending or not.

The Legacy of Earthbending: From Fantasy to Reality

Earthbending in Avatar: The Last Airbender is a fantastic art, yet it feels tangible and believable because of all these real-world connections. Watching an Earthbender heft a rock chunk might inspire you to look up Hung Gar kung fu, or seeing the walls of Ba Sing Se could spark interest in the Great Wall of China. The show’s creators (Bryan Konietzko and Michael Dante DiMartino) crafted Earthbending and the Earth Kingdom as a homage to the strength of human culture and martial arts. By basing bending moves on authentic styles, they ensured each fight had weight and authenticity – we subconsciously think “hey, I recognize that move!” when Toph drops into a horse stance or when an Earth Kingdom guard performs a palm strike. By weaving in legends like Oma and Shu or historical nods like the Dai Li’s name, they gave depth to the narrative that adults can appreciate while kids enjoy the action on the surface.

For both young fans and adult enthusiasts, Earthbending offers something to connect to. Children might simply admire the cool rock-tossing heroes, but as they grow older, they might discover the rich tapestry of influences underlying it – the kung fu styles, the dynasties, the philosophies. It’s a testament to ATLA’s worldbuilding that learning about Earthbending can be a mini history lesson and martial arts demo all in one. Perhaps it even inspires some viewers to take up a martial art or read about the history of China and Japan.

In the end, Earthbending’s essence can be summed up in the traits of its practitioners: strong, enduring, and true to themselves. Whether it’s Bumi’s crafty patience, Toph’s groundbreaking (literally!) innovations, or Kyoshi’s uncompromising justice, Earthbenders teach us that true strength isn’t just about brute force – it’s about stability, wisdom, and listening to the world around you. And those ideals are as relevant in our world as they are in Avatar’s. So next time you see a rocky hillside or a majestic stone building, take a moment to feel that Earth Kingdom vibe – the enduring, balanced energy that comes from centuries of tradition and the steadfast people who carry it on. In the words of the badgermoles: Dig deep, stand firm, and let the music (of the earth) move you!

Sources: The information above was drawn from Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra episodes and canon comics, as well as insights from the official Avatar Wiki and interviews. Notable references include the Avatar Wiki pages on Earthbending and Earth Kingdom culture, a Men’s Health interview with Sifu Kisu on the martial arts behind bending, and the Stanford Daily analysis of Avatar’s historical parallels, among others. These references help illuminate the real-world connections that make Earthbending and the Earth Kingdom feel so immersive and authentic.

Avatar: Bending Styles & Weapons

Interested to learn more about “Avatar: The Last Airbender”? Check out our article “The Exact Martial Arts Styles Behind Avatar: The Last Airbender Bending” to learn more about the Chinese Martial Arts Styles, Weapons, and Philosophy within the show!