Table of Contents

- Prelude: Before the Battles

- I. Early Foundations: Defenders of the Temple (Sui–Tang Dynasties)

- II. Turmoil and Destruction: The Yuan–Ming Transition

- III. Renewed Strength and Coastal Warfare (Ming Dynasty)

- IV. The Final Imperial Era (Late Ming to Early Qing)

- V. Shaolin in the Modern Era: Local Defense and the Temple’s Final Battle

- Conclusion: A Legacy Written in Both Dharma and Steel

For more than 1,500 years, the Shaolin Temple has stood as a symbol of Chinese martial excellence. While legends and folklore often exaggerate the fighting prowess of Shaolin’s warrior-monks, the historical record paints a story no less compelling: times of chaos, imperial struggles, bandit raids, foreign incursions, and national collapse all saw Shaolin monks take up arms—not for conquest, but for survival, loyalty, and the protection of the communities around them.

What follows is a fully documented chronology of the real battles and military engagements in which Shaolin monks participated, from the temple’s earliest centuries to its final major conflict in 1928. These accounts come from imperial steles, dynastic histories, academic research, and regional records. They are the foundation upon which Shaolin’s martial legacy was built.

Prelude: Before the Battles

The Destruction of 574 CE (Northern Zhou Dynasty)

Long before the Shaolin Temple became associated with martial discipline, the monastery endured a devastating blow in 574 CE, when Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou imposed a sweeping anti-Buddhist purge. Temples across the empire were closed or destroyed; at the Shaolin Monastery, buildings were dismantled, lands confiscated, and the community of monks forcibly dispersed.

Although the temple was restored under the Sui Dynasty a few years later, the destruction of 574 left a lasting impression. It exposed just how vulnerable a monastery could be in periods of political upheaval. When instability returned at the end of the Sui Dynasty, Shaolin’s monks—shaped by the memory of earlier persecution—were no longer willing to remain undefended.

This context sets the stage for the first historically documented example of Shaolin monks taking organized action to protect their community.

References:

- 《周书》 (“Book of Zhou”), Emperor Wu’s Buddhist suppression edicts, Jiande 3 (574 CE).

- Guang Xing, “The Buddhist Suppression under Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou”, Journal of Chinese Religions.

- Dengfeng County Gazetteer (登封县志), section on early Shaolin history.

- “建德毁佛” (574 Anti-Buddhist Purge) entries in Zhongguo Fojiao Zongjiao Shiliao Huibian (中国佛教宗教史料汇编).

- Shaolin Temple historical overview, referencing destruction and renaming to 陟岵寺 (Zhìhù Temple) under Emperor Jing of Northern Zhou and name restoration under Emperor Wen of Sui.

- Meir Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery (University of Hawai‘i Press), contextual discussion of pre-Sui monastic vulnerabilities.

I. Early Foundations: Defenders of the Temple (Sui–Tang Dynasties)

c. 610 CE — Defense Against Bandit Raids (Sui Dynasty)

During the violent collapse of the Sui Dynasty, roving bandits swept across Henan and threatened the young Shaolin Temple. This time, unlike in 574, the monks did not scatter. Instead, they organized themselves into a cohesive defensive force, taking up arms—primarily wooden staves—to repel the attackers and safeguard their monastery.

Contemporary accounts note that this defensive effort was disciplined and coordinated, marking the earliest clear emergence of the Shaolin Temple’s martial organization, a practical skill born from necessity and shaped by the memory of past destruction.

References:

- Dengfeng County Gazetteer (登封县志), Sui–Tang era temple records of bandit raids.

- Meir Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery, Chapter 1 — early martial organization and staff techniques.

- “Shaolin During the Sui Dynasty,” martial states in Martial Arts Culture & History summary referencing Sui-era raids and militia formation.

- Regional monastic chronicles noting Shaolin monk defensive mobilization during Sui collapse.

621 CE — The Battle of Mount Huanyuan (Hulao) and the “Thirteen Monks”

The most famous early instance of Shaolin military action occurred when thirteen Shaolin monks aided Li Shimin, the Prince of Qin (and future Emperor Taizong), during his campaign against the warlord Wang Shichong.

Historical accounts describe the monks:

- assisting in the capture of Wang’s fortified estate in Cypress Valley,

- seizing Wang’s nephew during the fighting,

- and contributing directly to Li Shimin’s decisive victory at the Battle of Hulao, which led to the fall of Luoyang and the rise of the Tang Dynasty.

In gratitude, Emperor Taizong rewarded Shaolin with land, a water mill, and an official letter of thanks in 626 CE.d

A stone stele erected in 728 CE still preserves the names of the thirteen warrior-monks who distinguished themselves in this campaign—one of the earliest physical inscriptions confirming the Shaolin monks’ martial role.

References:

- 728 CE Shaolin Stele (唐开元二十年碑), inscribed under Emperor Xuanzong; lists participating monks and commemorates battlefield assistance.

- Jiu Tang Shu (旧唐书) & Xin Tang Shu (新唐书) — annals of Li Shimin’s campaign against Wang Shichong.

- Meir Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery, detailed analysis of the campaign and Shaolin’s role.

- Dengfeng Gazetteer, recounting the Cypress Valley (柏谷坞) engagement and capture of Wang Shichong’s nephew.

- Modern analysis summarized in: K. Szczepanski, “The Legend of Shaolin Monk Warriors,” ThoughtCo.

8th Century — Tang Patronage and the Shadow of Persecution

Through the Tang dynasty, Shaolin remained influential and occasionally supplied monks to assist local officials. Although historical combat records from this period are sparse, the temple’s loyalty to the Tang throne was remembered for centuries.

During the 841 CE anti-Buddhist persecutions under Emperor Wuzong, Shaolin was notably spared. Records suggest that the emperor admired Li Shimin’s legacy and respected Shaolin’s earlier military service. The 728 stele itself served as a symbolic reminder to future rulers of the monks’ dedication.

References:

- 728 CE Shaolin Stele — commemoration of loyalty to Tang.

- Records of Emperor Wuzong’s 841 CE anti-Buddhist suppression in Zizhi Tongjian (资治通鉴).

- Wilkinson, Chinese History: A Manual — Tang religious policy and exceptions.

- Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery, discussion of Shaolin’s prestige and survival of Wuzong’s purge.

II. Turmoil and Destruction: The Yuan–Ming Transition

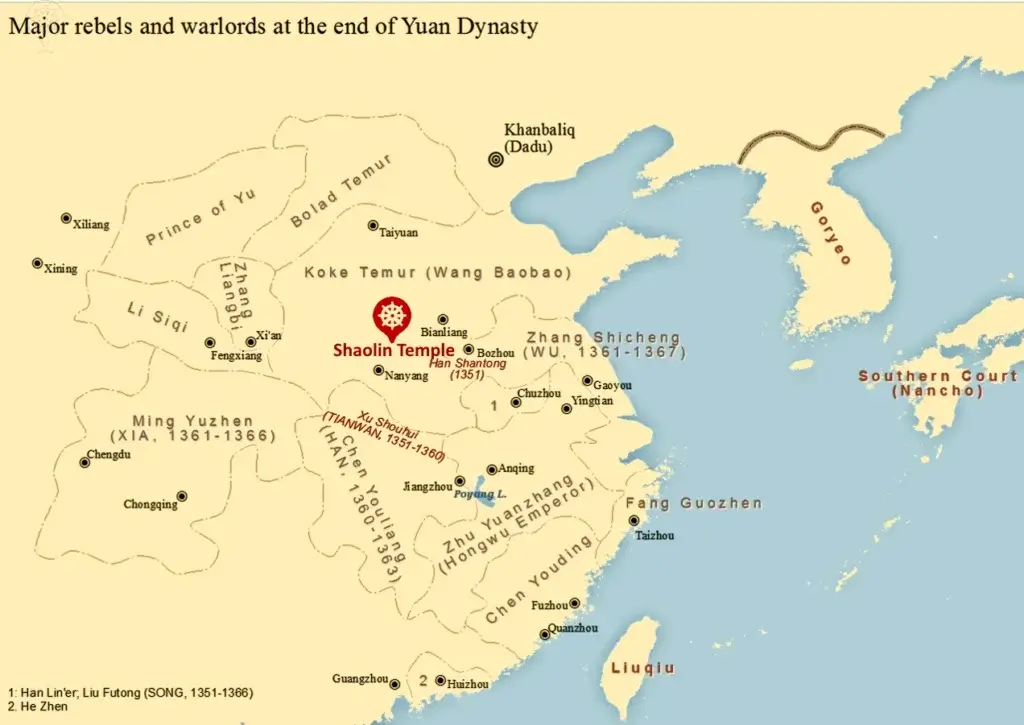

1351–1356 — The Red Turban Rebellion and the Sack of the Temple

As the Mongol Yuan Dynasty collapsed, China erupted into the Red Turban Rebellion. The Shaolin Temple was caught in the conflict when rebel-bandits attacked around 1351. The monks attempted to defend the monastery but were overwhelmed.

The outcome was devastating:

- The Shaolin Temple was looted and burned.

- Many monks were killed or scattered.

- The temple remained abandoned for several years.

Later folklore reframed this defeat as a miraculous victory aided by the Bodhisattva Vajrapani—a mythic transformation of a tragic loss into a tale of divine protection. Historically, however, the Red Turban attack stands as one of Shaolin’s darkest chapters.

References:

- History of Yuan (元史) and Red Turban uprising accounts.

- Dengfeng County Gazetteer, Yuan–Ming transitional notes on temple destruction.

- Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery, chapter on the 14th-century devastation.

- Folkloric reinterpretations documented in local chronicles tying Vajrapāṇi to Shaolin (noted explicitly as later mythic embellishment).

III. Renewed Strength and Coastal Warfare (Ming Dynasty)

1511 — Battle Against Bandit Armies

By the early 1500s, Shaolin had rebuilt both spiritually and martially. A Ming record from 1511 states that 70 Shaolin monks died in combat against bandit forces, suggesting that the temple maintained a sizable and organized corps of trained warrior-monks. Although details of the battle are sparse, the casualty number alone indicates the scale of the conflict and the seriousness with which Shaolin monks engaged in regional defense.

References:

- Ming Dynasty local records noting monk casualties during regional bandit suppression.

- K. Szczepanski, “The Legend of Shaolin Monk Warriors,” ThoughtCo summary of 1511 event.

- Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery, references to Shaolin’s military mobilization in early Ming.

1553–1555 — The Shaolin Monks vs. the Wokou Pirates

One of Shaolin’s greatest documented military achievements took place during the Ming Dynasty’s struggle against the wokou—pirates of mixed Japanese, Chinese, and Portuguese origin who terrorized China’s southeastern coast.

Mobilization

With imperial forces stretched thin, officials recruited warrior-monks from:

- Shaolin Temple (Henan)

- Funiu Mountain

- Wutai Mountain

The Shaolin contingent soon proved exceptional.

References:

- Ming military archives and local gazetteers describing monk mobilization.

- Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery, detailed reconstruction of Shaolin’s role against the wokou.

- Jiangsu and Zhejiang provincial records on anti-pirate campaigns.

- K. Szczepanski, “Shaolin Monks vs Japanese Pirates,” ThoughtCo.

July 21, 1553 — Victory at Wengjiagang

A force of 120 Shaolin monks, led by the monk-general Tianyuan, completely annihilated a pirate band of similar size. Historical accounts state:

- The monks killed the entire pirate force.

- They suffered only four casualties.

- They pursued the remaining pirates for ten days, leaving no survivors.

Earlier that year, Shaolin monks had also won a significant engagement at Mount Zhe near Hangzhou.

References:

- Ming campaign reports describing the monk-general Tianyuan and the annihilation of pirate forces.

- Zhejiang coastal defense archives referencing the Wengjiagang battle.

- Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery, citing contemporary sources on casualty ratio and pursuit.

1555 — A Costly Defeat and Withdrawal

A later campaign in 1555 ended in defeat due to the poor strategy of a Ming general supervising the monk troops. After this loss, Shaolin withdrew from frontline combat roles.

Recognizing their contribution, the Ming court repaired and expanded the temple and granted tax exemptions—a rare honor directly tied to martial service.

References:

- Ming military reports noting failed engagement due to strategic errors by command officers.

- Temple records indicating cessation of frontline service afterward.

- Ming court decrees on repairs, land grants, and tax exemptions awarded to Shaolin after the campaigns.

IV. The Final Imperial Era (Late Ming to Early Qing)

1560s–1630s — Continued Recruitment and Last Stands for the Ming

Historical sources indicate that the Ming government recruited Shaolin monks at least six times for different military campaigns after the pirate wars.

General Qi Jiguang, the famed anti-pirate commander, even consulted martial artists—including Shaolin monks—to refine troop training methods. By the 1630s, as rebel armies swept across China, Shaolin monks again fought on behalf of the Ming. They suffered defeat alongside the collapsing dynasty.

References:

- Qi Jiguang (戚继光), Ji Xiao Xin Shu (纪效新书) — references to consultations with monks and use of martial artists in training.

- Ming military records documenting recruitment of “monk-soldiers” (僧兵).

- K. Szczepanski, ThoughtCo, summary of late Ming engagements.

- Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery, discussion of six documented Ming-era monk mobilizations.

1641 — The Sacking by Li Zicheng’s Rebels

In one of the final tragedies of late imperial China, the rebel leader Li Zicheng targeted Shaolin Temple during his campaign through Henan.

Historical accounts describe:

- The complete destruction of the monastic fighting force.

- Monks killed or driven into hiding.

- The temple plundered and left in ruins.

Shaolin remained largely abandoned for decades afterward. This event effectively ended Shaolin’s role as a major military power in pre-modern China.

References:

- History of Ming (明史) — accounts of Li Zicheng’s march through Henan.

- Dengfeng Gazetteer entries on destruction of Shaolin by rebel troops.

- Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery, analysis of Shaolin’s collapse as a military institution after 1641.

- Regional histories noting decades of abandonment following the attack.

V. Shaolin in the Modern Era: Local Defense and the Temple’s Final Battle

1912–1920 — Shaolin Militia and Regional Security

With the fall of the Qing dynasty and the birth of the Republic, China descended into political chaos. Local authorities recognized the need for stable guardians and officially appointed monk Yunsong Henglin as head of a Shaolin Militia Guarding Corps.

He:

- trained young monks in modernized combat skills,

- armed them for patrol duty,

- and protected surrounding villages.

During the famine of 1920, when starving bandits threatened the region, Henglin led his monks in multiple successful defensive operations. Records state that thanks to their efforts, local residents “lived and worked in peace” despite widespread lawlessness.

References:

- Republican-era Henan administrative records appointing Henglin as militia leader.

- Monastic documents referencing the Shaolin Guarding Corps (守护团).

- Accounts of 1920 famine-era bandit suppression in Dengfeng county histories.

- Eyewitness/monastic oral histories preserved in early PRC local chronicles.

1927–1928 — The Warlord Era and the Burning of Shaolin

The last major conflict involving Shaolin monks came during the violent Warlord Era.

Shaolin Temple Supports Warlord Fan Zhongxiu

The temple gave refuge to Fan Zhongxiu, a warlord who had once trained at the Shaolin Temple. This allegiance made the temple a military target.

References:

- Warlord-era military reports and local histories documenting Fan Zhongxiu’s occupation of the temple.

- Primary references to Shi Yousan’s shelling and burning of the monastery (including destruction of scriptures).

- Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery, concluding chapter on the 1928 destruction and aftermath.

- Dengfeng Gazetteer and Henan provincial archive references to temple reconstruction delays.

March 15, 1928 — Temple Set Ablaze

Fan’s rival, Shi Yousan, launched a retaliatory attack. His troops:

- set fire to the monastery,

- destroyed ancient halls and towers,

- killed monks,

- and obliterated over 5,000 Buddhist scriptures and numerous cultural relics.

The 1,400-year-old temple was left in ruins. It would not be fully restored until the late 20th century.

This tragic event marks the final historically documented battle involving Shaolin monks.

References:

- Contemporary reports of the battle between Fan Zhongxiu and Shi Yousan.

- Remaining Shaolin monastic testimonies recorded later in the century describing loss of relics and buildings.

- Cultural relics office surveys from the 1980s confirming which structures were original vs. ruined vs. restored.

Was The Shaolin Temple Really Empty After 1928?

(Short answer: No.)

Although the 1928 warlord attack left the Shaolin Temple in ruins, the monastery was never truly abandoned. A small group of dedicated monks—including figures such as Monk Yong Xiang, Shi Dechan, Shi Suxi, and later Shi De Qian (late 40s/50s on)—quietly kept Chan (Buddhist) practice and martial knowledge alive through war, famine, political upheaval, and the Cultural Revolution.

Much of Shaolin’s surviving traditional curriculum exists today because these monks preserved texts, recompiled damaged manuals, and continued training even when only a handful of practitioners remained. For example, Shi De Qian’s extensive work cataloguing forms and scriptures (discussed in our earlier article on the Shaolin Quan Pu) helped safeguard techniques that might otherwise have been lost forever.

Though life at the temple was harsh and often dangerous, Shaolin’s lineage endured—lean, hidden, but unbroken.

A full article on this extraordinary “survival era” (1928–1980s) is coming soon. Stay tuned.

Conclusion: A Legacy Written in Both Dharma and Steel

From defending their monastery in the 7th century to fighting pirates on the coast and navigating the chaos of warlord-era China, Shaolin warrior-monks left behind a verifiable record of courage, discipline, and loyalty. Their combat history is not one of aggression, but of duty—to their temple, to their people, and often to the state itself.

These documented battles form the backbone of Shaolin’s martial heritage. The legends that followed may have embellished the story, but the truth itself is rich enough: Shaolin’s monks were not only guardians of Buddhist wisdom, but also—when history demanded it—guardians of China.