Temples have been integral to Chinese culture for millennia. From majestic Buddhist monasteries in mountain enclaves to humble folk shrines in bustling cities, these sacred structures have long served as centers of worship, culture, and art. Over the centuries, China’s temple landscape evolved with each dynasty’s rise and fall, and with the spread of Buddhism, Daoism, Confucianism, and folk religions. Visitors today, however, might notice fewer temples in China’s cities compared to places like Thailand or Japan – a contrast rooted in historical developments and modern changes. By exploring the history of Chinese temples across dynasties, the religious traditions they embody, and major cultural shifts, we can understand their current state and enduring significance.

Historical Overview: Temples Through the Dynasties

The concept of the “temple” in China stretches back to antiquity. In ancient dynasties, ritual halls and ancestral shrines were early forms of temples used to honor heaven, earth, and forebears. For example, imperial China maintained grand sacrificial complexes like the Temple of Heaven (天坛) in Beijing, where emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties performed rites to Heaven for good harvests. Every dynasty built ancestral temples (zongmiao) to venerate royal ancestors and Confucian temples (wenmiao) to honor sages, underscoring the temple’s role in state ideology and cultural continuity.

Buddhist temples entered the scene during the Han Dynasty. Buddhism arrived from India in the 1st century AD, and according to tradition the very first Buddhist temple, the White Horse Temple (白马寺) in Luoyang, was established around 68 AD under Emperor Ming’s patronage. In subsequent Period of Disunion (3rd–6th centuries) and Tang Dynasty (618–907), Buddhist monasteries proliferated. By the mid-Tang era, thousands of temples dotted the empire, supported by imperial patronage and public devotion. Tang capital Chang’an alone boasted numerous grand monasteries. However, dynastic politics sometimes reversed this growth – notably in 845 AD Emperor Wuzong’s edict closed or destroyed over 4,000 monasteries and 40,000 smaller shrines, in an effort to curb Buddhism’s influence. Such episodic suppressions aside, Buddhism remained deeply rooted: even today, the Great Wild Goose Pagoda and other Tang-era temple sites in Xi’an attest to that golden age.

Daoist temples also became prominent by the early medieval era. Daoism, an indigenous religion, began organizing in the late Han (2nd century AD) and built its own temples and sacred sites. By the Tang Dynasty, Daoism enjoyed imperial favor (Tang emperors traced lineage to Laozi), leading to lavish Daoist temples (guan). Many Daoist sanctuaries were established in mountainous areas famed in lore – for instance, Mount Wudang’s temple complex, expanded in the Ming era, exemplifies an imperial-sponsored Daoist center. Meanwhile, Confucian temples emerged as state institutions; by Song and Ming times, virtually every prefecture had a Confucius Temple for educating scholars and holding ceremonies. According to historical records, around 1,560 Confucian temples existed nationwide during the Ming (1368–1644), rising to about 1,800 in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). These Confucian temples (often called 文庙) were not for deity worship but to honor Confucius and eminent Confucian sages with ritual offerings.

Throughout the late imperial era (Ming–Qing), China’s cities and villages were dense with temples of various kinds. An average county seat would host multiple Buddhist monasteries, one or more Daoist palaces, a Confucian temple (usually adjacent to the school), and assorted folk shrines. Rural areas maintained ancestral halls and earth-god shrines in each village. Different regions developed distinctive temple landscapes. For example, the southeast coast – areas like Fujian and Zhejiang – became known for abundant temples and Buddhist activity, earning Zhejiang the nickname “Buddhist Kingdom of the Southeast” (东南佛国). Even today, Zhejiang has over 4,000 temples, the most of any province, reflecting its rich legacy. In contrast, the far west in Tibet and Qinghai saw the flourishing of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries (Lhasa’s Potala and Labrang in Gansu among them), which were often large monastic cities in themselves. China’s temple heritage thus evolved unevenly across dynasties and regions – waxing during periods of prosperity and imperial support, and waning during periods of war or anti-religious policy, but always remaining a vital thread in the cultural fabric.

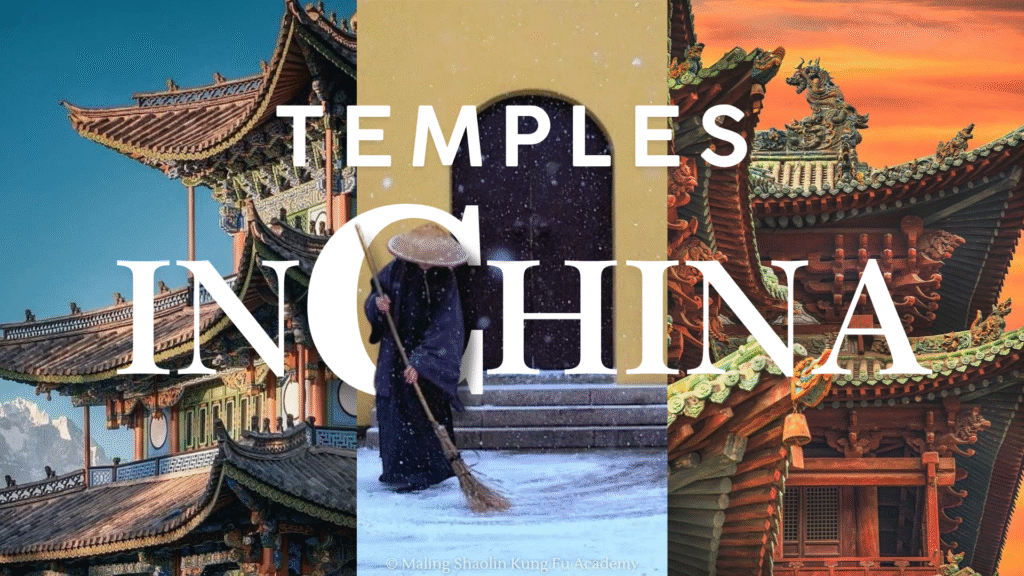

Religious Traditions and their Temples

Chinese temples have served diverse religious traditions, each with its own philosophy and style of worship. Broadly, temple architecture and functions reflected the needs of Buddhism, Daoism, Confucianism, and folk religion, often coexisting in the same communities. In fact, it was not unusual for multiple traditions to syncretize – the famous Hanging Temple (悬空寺) in Shanxi even enshrines Buddha, Laozi, and Confucius together under one roof. Below is an overview of the major temple traditions:

Buddhist Temples (寺院) – Buddhist temples (also called monasteries) are dedicated to the Buddha and bodhisattvas. Since the Eastern Han introduction of Buddhism, Chinese Buddhist temples became centers of monastic life, meditation, and public devotional practice. They typically feature statue-filled halls, pagodas (stupas), and living quarters for monks or nuns. In early eras, temple layouts were influenced by Indian designs – for example, the earliest temples were built around a central pagoda. By the Tang era, Chinese Buddhist temples evolved into grand complexes with multiple halls aligned along a central axis. Famous examples include the Shaolin Temple in Henan (where Chan/Zen Buddhism and martial arts thrived) and Lingyin Temple in Hangzhou, a major Chan monastery still active today. Buddhist temples often amassed significant wealth and land, serving as both spiritual sanctuaries and community centers. This prominence occasionally drew backlash (as in 845 AD, when Buddhist assets were seized by the state), yet Buddhism endured. Over 2,000 years, it became ingrained in Chinese society – today, Buddhist temples remain the most numerous in China, hosting daily worship, festivals, and pilgrims.

Daoist Temples (道观) – Daoist temples are devoted to the gods and immortals of the Daoist pantheon and to the pursuit of spiritual cultivation. Daoism, being China’s native organized religion (formally dating to the 2nd century AD), built its earliest temples as ritual centers for daoshi (priests) and adherents. A Daoist temple (often called guan or gong) typically enshrines deities such as the Jade Emperor, Laozi, or the Queen Mother of the West, depending on the sect. Many Daoist temples were established in secluded natural settings – mountains and grottoes deemed sacred – aligning with Daoism’s emphasis on harmony with nature. For example, the WuDang Mountains in Hubei host a complex of Daoist temples and palaces built with imperial support during the Ming era. Layouts of Daoist temples follow traditional Chinese courtyard architecture (south-facing, symmetric along an axis) similar to Buddhist temples, though the iconography differs (Daoist halls feature immortal figures, constellation gods, etc., rather than Buddhas). Throughout history, the status of Daoist temples rose and fell – Tang emperors lavishly funded some, while certain persecutions of “superstition” in later eras targeted them. Nonetheless, Daoist temples have persisted as centers for rituals like fasting, offering, and divination, and many historical Daoist sites (Beijing’s Baiyun Guan, Shanghai’s City God Temple, etc.) are still in use.

Confucian Temples (文庙) – Though Confucianism is often regarded as a philosophy or ethical system, it developed temple-like institutions dedicated to Confucius (Kongzi) and other revered sages. A Confucian temple, usually called Kong Miao or wenmiao, was found in virtually every major city by late imperial times. These temples served as ceremonial spaces where officials and scholars offered sacrifices to Confucius, especially on his birthday, as a way to affirm moral and social order. Architecturally, Confucian temples resemble grand academies: spacious courtyards, gates, and halls with spirit tablets instead of deity statues. The Temple of Confucius in Qufu (Shandong) – Confucius’s hometown – is the most famous, expanded over centuries into a vast complex. By the end of the Qing dynasty, around 1,560–1,800 Confucian temples existed across China, often adjacent to government schools. Unlike Buddhist/Daoist temples, these had no resident monks or priests; rather, they were maintained by local officials or literati. Many Confucian temples were damaged or repurposed in the 20th century, but several hundred survive today as cultural heritage sites or museums. Some still host annual commemorative rites, reflecting Confucianism’s continued cultural influence.

Folk Religion and Ancestral Temples – Beyond the formal religions, China has a rich tapestry of folk beliefs, and countless local shrines and temples have been dedicated to regional deities, heroes, and ancestors. For example, the Mazu temples along China’s southeast coast honor Mazu, the goddess of the sea, and have been centers of marine folk culture since the Song dynasty. Every Chinese city in imperial times also had a City God Temple (城隍庙) protecting the city’s spirit – a tradition standardized in the Ming era, where an officially appointed City God was worshipped in a central temple. Villages likewise maintained small shrines to the Earth God (土地庙) and clan ancestral halls (宗祠) to venerate lineage ancestors. These folk temples often blended practices from Buddhism or Daoism without strict sectarian identity. They were typically managed by local communities or guilds. While it is difficult to quantify their numbers, they likely numbered in the hundreds of thousands historically, forming the spiritual backbone of Chinese grassroots society. However, folk temples were also the most vulnerable to upheaval; many were destroyed as “superstitious” during the 20th century. In recent decades some have been revived – for instance, new Mazu temples have been built in coastal areas – but many others remain only in memory or have been absorbed into the authorized Buddhist/Daoist institutions.

20th-Century Turmoil and the Decline of Temples

China’s turbulent 19th and 20th centuries brought dramatic changes to the fate of temples. Late imperial conflicts and rebellions already took their toll – notably, during the Taiping Rebellion (1850s), the anti-traditional Taiping forces destroyed innumerable Buddhist and Daoist temples across central China in their campaign against “idolatry”. The fall of the Qing in 1911 and the rise of the modern Chinese state further transformed religious institutions. In the early Republican era, some temple lands were confiscated or turned into schools and government offices under policies of secularization. Nonetheless, many temples survived into the 20th century, continuing local religious life in the midst of warlordism and Japanese invasion.

The greatest impact came with the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). During this mass political movement, temples and religious artifacts were denounced as feudal “olds” to be eradicated due to efforts to promote rational thinking and public health over superstition and passive fatalism. Red Guards and officials targeted places of worship across the country, leading to widespread decomitioning of religious institutions. For example, Mount Wutai, one of Chinese Buddhism’s holiest sites, had over 300 temples before the Cultural Revolution, but afterward only around 30 remained; hundreds of monks and nuns were expelled, and priceless scriptures and statues were lost. In one city (Taiyuan in Shanxi), out of 190 temple sites, all but a dozen were demolished during this period. Such incidents were repeated nationwide: ancient monasteries were razed, Daoist and folk shrines demolished or converted to secular use, and Confucian monuments defaced. This decade of iconoclasm, combined with earlier anti-religious campaigns, meant that by the late 1970s China’s religious infrastructure was a shadow of its former self. Essentially, virtually no temple was left untouched – many centuries-old institutions vanished, and those that survived did so in a lessened or repurposed state.

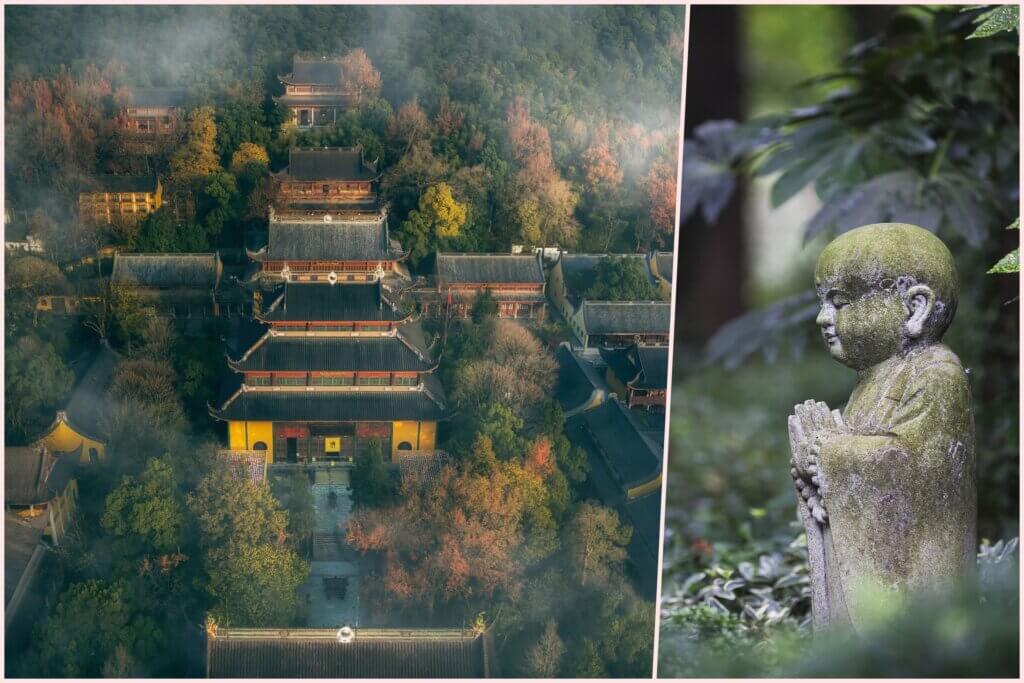

Temples in China Today: Revival and Realities

Since the 1980s, China has seen a revival of religious practice and the restoration of many temples, though the landscape remains very different from neighboring countries. The government’s gradual acceptance of religious practices allowed communities to rebuild or reopen temples under regulatory oversight. As a result, the number of active temples has grown significantly in recent decades (often with an eye to cultural tourism as well as spiritual needs). By the 21st century, China has approximately 33,000 Buddhist temples open for worship, along with about 9,000 Daoist temples. (These figures include temples of various branches – for example, the 33,000 Buddhist sites range from large Han Chinese monasteries to Tibetan lamaseries and Theravada temples in Yunnan.) In addition, there are still hundreds of Confucian temples preserved as heritage sites, and untold numbers of folk shrines either unregistered or subsumed under the major religions.

Despite this revival, China’s temple density remains relatively low compared to some East Asian neighbors. Japan, for instance, preserved most of its religious sites through the 20th century and today boasts roughly 77,000 Buddhist temples and 80,000 Shinto shrines across the country – a far higher concentration per capita and per area than in China. The contrast is rooted in history: whereas Japan did not experience a modern anti-religious upheaval on the scale of China’s Cultural Revolution (Japan’s separation of Shinto and Buddhism in the Meiji era caused some temple closures but nowhere near the comprehensive destruction seen in China), China’s temple network had to be rebuilt almost from the ground up after the 1970s. Even now, many communities in China that historically had temples have only recently restored them, if at all, and new temples require government approval. In mainland China’s cities, temples are fewer and often tucked away as protected cultural relics amid urban development, whereas in Japan it is common to find a shrine or temple in every neighborhood.

Another important distinction is the role of temples today. Many famous temples in China have been restored primarily as historical monuments and tourist attractions, even if they also function as religious institutions. For example, Beijing’s Temple of Heaven – once an imperial ritual altar – is now a public museum park with no active religious ceremonies. Similarly, the big Confucian temples (like those in Qufu or Beijing) serve mainly as museums and sites for occasional cultural events. On the other hand, numerous Buddhist and Daoist temples are actively used for worship. Temples such as Shaolin Temple (Henan), Lama Temple (Yonghe Temple) in Beijing, Lingyin Temple in Hangzhou, or White Cloud Temple in Beijing have resident monks or priests and daily rituals, even as they welcome throngs of tourists. In fact, the official counts of 33,000 Buddhist and 9,000 Daoist temples refer to those registered as active religious venues – meaning they host clergy and regular services. These include both famous pilgrimage sites and countless small community temples now operating again. Still, the dual identity is palpable: one can see devotees lighting incense alongside sightseers with cameras.

In contemporary China, temples thus straddle the line between the sacred and the secular. They remain important religious centers for millions – during festivals like Chinese New Year or Buddha’s Birthday, temples fill with worshippers making offerings and praying. At the same time, temples are cherished for their historical architecture, art, and the cultural continuity they represent. The Chinese government often promotes major temples as part of national heritage and tourism (for example, several temple complexes are UNESCO World Heritage sites). This dual emphasis helps fund preservation, but also means some temples prioritize cultural display over religious activity. Smaller folk shrines, where revived, tend to serve local spiritual needs more intimately, though many such grassroots temples operate in a semi-official capacity.

In summary, the landscape of Chinese temples today is the product of a long, dynamic history. For over two thousand years, temples in China have been built and rebuilt, patronized and purged, reflecting the ebb and flow of dynasties, the spread of great teachings like Buddhism and Daoism, and the resilience of popular faith. The relative scarcity of temples in modern China – especially when contrasted with temple-rich neighbors – can be attributed in part to historical reforms and prolonged periods of secularization, during which religious spaces were repurposed or deprioritized in efforts to align with broader goals of public well-being and national progress. Yet, what survives and is now being rejuvenated is testament to the enduring place of spirituality in Chinese life. Whether as active sanctuaries where incense burns and chants echo, or as historic monuments where tourists marvel at painted eaves and stone pagodas, China’s temples continue to inspire and educate. They stand as living symbols of the country’s cultural heritage – bridges between China’s ancient past and its ever-evolving present, inviting visitors and worshippers alike to step into the flow of history and reflect on the beliefs and traditions that have shaped this civilization.