Imperial Unification of China (Qin and Han)

With the fall of the Zhou came centuries of warfare and division. But from the chaos of the Warring States, a new vision of China emerged—one not ruled by feudal lords, but unified under a central authority—the imperial unification of China. In Part 2 of The Dynasties That Shaped China, we explore the pivotal transformation that occurred under the Qin (秦朝) and Han (汉朝) dynasties. The Qin’s short but powerful reign set the stage for over two millennia of imperial rule, introducing sweeping reforms in law, writing, and infrastructure. The Han then built on that foundation, ushering in a golden age of culture, science, diplomacy, and Confucian humanism. Here, we witness the moment when China became a true empire—centralized, expansive, and culturally radiant.

The Qin Dynasty (Qíncháo 秦朝, 221–206 BCE)

After centuries of fragmentation, the state of Qin emerged victorious from the Warring States wars, unifying China in 221 BCE under King Ying Zheng, who declared himself Qín Shǐhuángdì (秦始皇帝) – “First Emperor of Qin.” Although the Qin Dynasty was short-lived (15 years with only two emperors), it established the template of centralized imperial rule that would last for over two thousand years. Qin Shihuang proved to be an exceptionally bold, if ruthless, ruler who imposed sweeping changes on the newly unified realm.

Politically, Qin implemented centralization and Legalist governance. The empire was divided into administrative commanderies directly under the imperial court, abolishing the feudal fiefdoms of Zhou. Influenced by Legalist advisors (like Li Si), Qin Shihuang curtailed the power of hereditary nobles and enforced strict laws uniformly. The emperor is infamous for the 213 BCE “burning of books and burying of scholars” – a purge of certain classical texts and purported execution of 460 Confucian scholars – aimed at suppressing intellectual dissent. While historical accounts of this event may be exaggerated, it cemented Qin’s reputation for authoritarian control. Dissent was not tolerated; standardization and obedience were prized.

Crucially, the Qin Dynasty standardized China’s script, currency, weights and measures – a foundational achievement for national unity. Before unification, different states had varying writing styles. Qin Shihuang mandated a uniform small seal script for all of China, enabling administrative communications across diverse regions. Currencies and axle lengths of carts were standardized as well. These reforms broke down regional barriers and “promoted trade and communication across the empire”. The Qin legal code too was uniform, based on strict Legalist principles of reward and punishment.

Under Qin Shihuang, gigantic infrastructure projects were launched with mass labor. The most famous is the Great Wall: Qin linked and expanded walls that former northern states had built, creating a defensive Great Wall of China against nomadic incursions. Though the structure we know today was largely built in later dynasties, Qin’s effort was the first “great wall” unifying various segments. The Qin also built roads radiating from the capital Xianyang, standardized to facilitate swift troop movement and trade. Canals and irrigation works, like the Zhengguo Canal, were constructed to boost agriculture in the interior.

The dynasty’s most awe-inspiring project was the mausoleum of Qin Shihuang, guarded by the legendary Terracotta Army. Discovered in 1974 near Xi’an, this underground army of some 7,000 life-sized clay soldiers and horses was buried to protect the First Emperor in the afterlife. The Terracotta Army is not only a marvel of ancient artistry and mass production, but also a window into Qin military organization – the figures include infantry, archers, charioteers, and officers in battle formation.

The Qin Dynasty’s militarism was indeed formidable. Qin had conquered the six other major states by employing superior military technology and strategy (including iron weapons and large cavalry/chariot forces). Yet the same iron-fisted approach that unified China also sowed resentment. After Qin Shihuang’s death in 210 BCE, rebellions erupted against his overbearing heir. By 206 BCE, the Qin state collapsed amid civil war. However, the Qin Dynasty’s legacy far outlasted it. Subsequent Han rulers adopted Qin’s centralized bureaucratic system and many of its reforms. The very idea of China as a unified empire – “All-under-Heaven” – dates from Qin. Even the name “China” likely derives from “Qin” (via Sanskrit Cina). In short, Qin Shihuang’s brief experiment gave birth to the Chinese imperial model: centralized autocracy, standardized culture, and expansive infrastructure tying the realm together.

The First Emperor’s Quest for Immortality

Qin Shihuang was notorious not only for ambition in life but also for his obsession with cheating death. He dispatched expeditions to find mythical islands of immortals and consumed elixirs (containing mercury) prepared by court alchemists, hoping for eternal life. Ironically, these toxic “medicines” may have hastened his death. The great irony is that while the man perished, his legacy – in the form of policies and even his terracotta likenesses – achieved a kind of immortality in Chinese history.

The Han Dynasty (Hàncháo 汉朝, 206 BCE – 220 CE)

Emerging from the ashes of Qin’s collapse, the Han Dynasty founded by Liu Bang (posthumously Emperor Gaozu) became one of China’s greatest and most enduring dynasties. The Han era is considered a golden age in Chinese history – so influential that the main ethnic group in China still calls itself the “Han people” (Hànrén 汉人). Lasting over four centuries (interrupted briefly by the usurper Wang Mang’s Xin dynasty in 9–23 CE), the Han Dynasty presided over territorial expansion, flourishing trade, cultural achievements, and the formal establishment of Confucianism as state ideology.

Under the early Western Han (206 BCE – 9 CE), the emperors maintained much of the Qin administrative apparatus but tempered it with more moderate governance. Liu Bang himself had risen from peasant roots; he and his successors understood the need to win popular support after Qin’s harshness. The Han rulers reduced taxes and corvée labor burdens on peasants and adopted a more lenient legal code. Still, the empire was centralized and bureaucratic, with a capital at Chang’an (near modern Xi’an) teeming with officials. Notably, Emperor Wu of Han (Wǔdì 武帝, r. 141–87 BCE) ushered in a transformative era. At the advice of scholar Dong Zhongshu, Emperor Wu adopted Confucianism as the official state philosophy in 136 BCE, elevating it above other schools. He established an imperial academy to train civil servants in the Confucian classics, laying the groundwork for the later civil examination system. This policy of “Exalting the Confucian doctrine alone” (罢黜百家,独尊儒术) – traditionally attributed to Dong Zhongshu and Emperor Wu – meant that ethics and governance ideals from Confucius became the guiding light of the state. In practice, Han governance blended Confucian ideals of benevolence with Qin-inherited Legalist institutions (a phrase often summarized as “外儒内法”, seemingly Confucian on the outside but Legalist within). Nonetheless, the Han era saw scholar-officials esteemed and a vast corpus of literature compiled. Sima Qian, the great historian, wrote Records of the Grand Historian (Shǐjì 史记) around 94 BCE, pioneering China’s tradition of dynastic histories.

Culturally, the Han Dynasty experienced a brilliant flowering of arts and technology. Poetry and literature thrived; the fu genre (descriptive poetic essays) became popular. Han artisans produced exquisite lacquerware, silk textiles (the famous silk from Han traveled afar), and jade carvings. Han painting and music were also patronized – the imperial Music Bureau collected songs and dances. Education spread, and paper was invented (traditionally credited to Cai Lun in 105 CE). Indeed, one of the most impactful Han innovations was the invention of papermaking, which provided a cheaper writing medium than bamboo or silk. Other scientific advances included the world’s first seismograph (created by Zhang Heng c. 132 CE to detect distant earthquakes) and improvements in timekeeping with water clocks and sundials. The Han Chinese had a sophisticated understanding of astronomy; they plotted planetary motions and issued updated calendars regularly. The government established imperial medical institutes and compiled pharmacological texts, reflecting an emphasis on learning and public welfare.

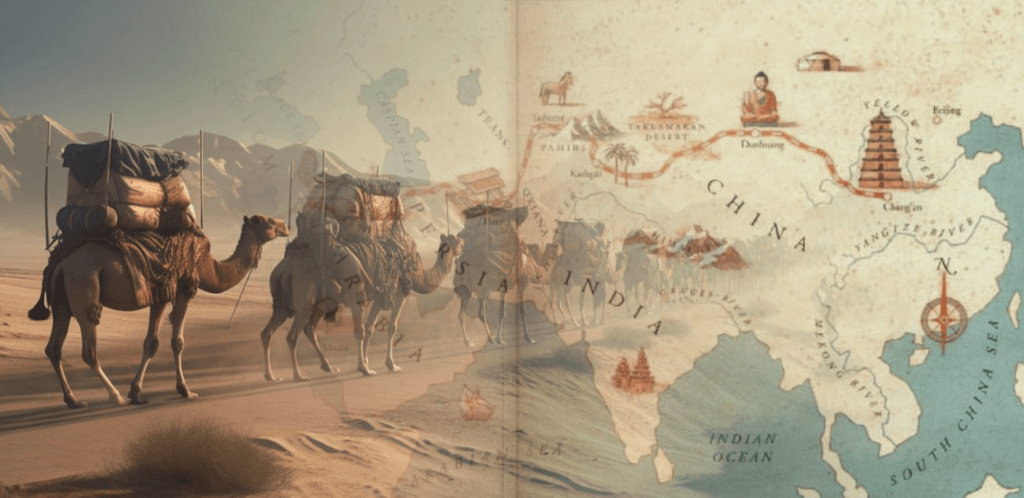

Meanwhile, the Han expanded China’s frontiers. Emperor Wu in particular was a vigorous campaigner. Han armies pushed into Central Asia, defeating the Xiongnu nomads who had harassed the northern borders. Around 130 BCE, the explorer-general Zhang Qian ventured west on diplomatic missions and effectively opened the Silk Road, enabling trade between China, Central Asia, and beyond. The Silk Road would become a conduit not just for silk and spices, but for ideas and religions. Han territory eventually extended into parts of Korea (the Han set up commanderies in northern Korea), south into northern Vietnam, and west into today’s Xinjiang region. This made the Han Empire contemporaneous with Rome in size and population – indeed, at its height Han China was on par with the Roman Empire in power and influence. It’s intriguing that Chinese historical consciousness often compares the Han and Rome; both were seen as great ancient empires. The term “Han people” itself, first used during the following period of disunion, honored the Han Dynasty’s golden age as a defining epoch of the civilization.

Religion and philosophy in Han times took on new dimensions. Confucianism was the state orthodoxy, promoting ideals of filial piety and moral governance. Yet Daoism also evolved – not just the philosophical Daoism of Laozi, but religious Daoist movements began emerging (such as the Five Pecks of Rice sect founded by Zhang Daoling in 2nd century CE). Buddhism too made its first inroads into China during the Eastern Han. A famous legend recounts that Emperor Ming (58–75 CE) dreamed of a golden figure, leading him to send envoys to India; they returned with scriptures and monks. In 67 CE the first Buddhist temple in China, the White Horse Temple (Báimǎ Sì 白马寺), was established in Luoyang. This marks the start of Buddhism’s slow but momentous integration into Chinese culture. By the end of Han, Buddhist communities and translations of sutras were growing, especially in the northwest – planting seeds for Buddhism’s blossoming in later eras.

The Han Dynasty era also witnessed the earliest known references to martial arts traditions. Han texts mention wrestling and fencing as military training. The historian Ban Gu recorded imperial guards practicing a form of grappling called shǒubó (手搏). General Qi Jiguang’s 16th-century martial writings even claim the origin of boxing arts (quan) dates to the Han. While much of this is retrospective lore, the martial ethos – valorizing archery, chariot-driving, and combat skills – was certainly present. Legendary figures like Huo Qubing, a young Han general who repeatedly defeated the Xiongnu, were celebrated in story and song. Over time, folk tales of Han heroes contributed to the martial heritage that later dynasties, and Shaolin monks, would look back on.

By 220 CE, the Han state had weakened due to palace intrigue (eunuch factions, empress dowagers) and peasant rebellions (like the Yellow Turban Rebellion, a Daoist-inspired uprising in 184 CE). The last Han emperor was a mere puppet before warlords who eventually dissolved the dynasty. Yet the Han Dynasty’s achievements in governance, culture, technology, and foreign contacts set a lasting standard. So profound was its impact that every subsequent Chinese dynasty sought to model itself on the Han, and later historians called themselves the descendants of Han. As a 2nd-century stone inscription boasts, the Han “required cultural accomplishment from their public servants” and attained such heights that “every ensuing dynasty sought to emulate them”.

The Silk Road and Cultural Exchange

Beginning in the Han era, long-distance trade routes linked China to Central Asia, India, and the Mediterranean. The Silk Road network carried Chinese silk westward in exchange for horses, glassware, and gold. This era saw early instances of cultural exchange: exotic foods like grapes, pomegranates, and walnuts were introduced to China; Persian and Indian musicians and dancers appeared at the Han court. Most significantly, Buddhism traveled along the Silk Road, carried by monks and merchants into China during the 1st century CE. The cosmopolitan impulse started under Han would later flourish, especially under the Tang Dynasty.