Golden Ages of Culture and Innovation (Tang and Song)

As the chaos of the Six Dynasties gave way to reunification under the Sui and consolidation under the Tang, China entered a golden era defined by cultural brilliance, political stability, and expansive innovation. Building on the foundations laid by earlier dynasties, the Tang and Song periods ushered in profound advancements in art, science, literature, and philosophy. For the Shaolin Temple and Chinese martial traditions, this was a transformative time—one that elevated the warrior monk from regional protector to imperial icon. While the Tang Dynasty championed martial valor and battlefield heroism, the Song Dynasty deepened the spiritual and scholarly dimensions of kung fu. Together, these dynasties forged an enduring legacy that fused physical discipline with cultural refinement, setting the stage for many of the practices and values that still define traditional Chinese martial arts today.

The Tang Dynasty (Tángcháo 唐朝, 618–907 CE)

After the Sui Dynasty’s brief unification and collapse, the Tang Dynasty rose in 618 CE, inaugurating one of the most glorious eras in Chinese history. The Tang period is often regarded as a golden age of cosmopolitan culture, economic prosperity, and imperial power. Under Tang rule, China reached heights of art and literature, made strides in technology, and enjoyed an outward-looking engagement with the wider world.

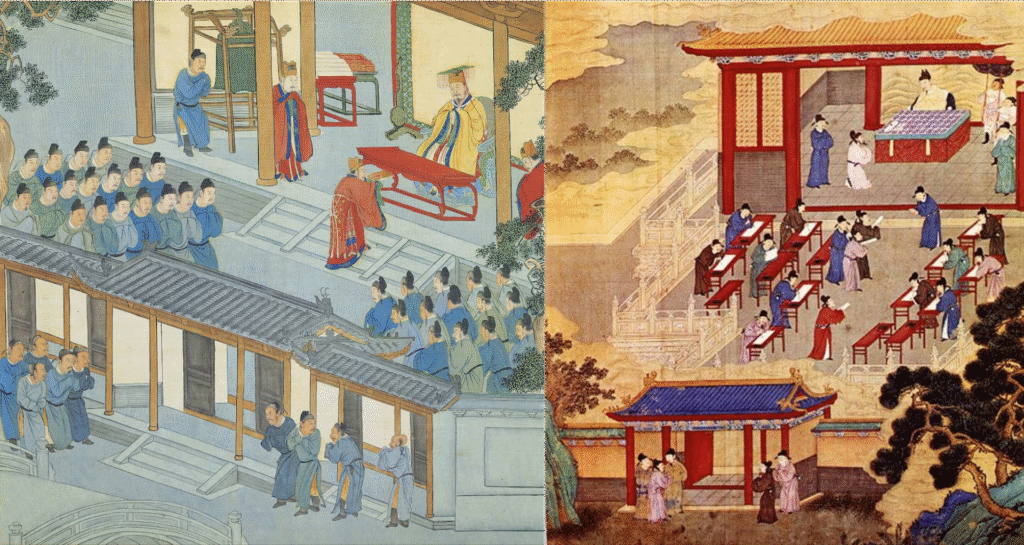

The Tang emperors, who came from the Li family, expanded on the systems set up by the Sui Dynasty—especially centralized government and fair land ownership (known as the “Equal-field system”). Emperor Taizong (reigned 626–649), one of the most respected early rulers, led by example. He welcomed honest advice, even when it was critical, and surrounded himself with wise and capable officials, including the well-known Chancellor Wei Zheng. The government system – with its civil service examinations revived and expanded – recruited officials based on merit in Confucian classics, a practice that became entrenched. The Tang legal code was advanced and humane for its time, and it became a model for other East Asian countries. At its zenith, the Tang capital Chang’an (present-day Xi’an) was the largest city in the world, a thriving metropolis of perhaps two million people, filled with merchants, scholars, monks, and diplomats from across Asia, the Middle East, and beyond. As a testament to Tang’s international outlook, Chang’an had thriving communities of Persians, Arabs, Indians, Sogdians, Koreans, Japanese, and others – with Zoroastrian temples, Nestorian Christian churches, and myriad Buddhist sects coexisting in the city.

Tang China’s territory and influence spread far. Militarily, the Tang emperors (and occasionally empress – the only female monarch, Empress Wu Zetian, ruled in her own name from 690–705) expanded into Central Asia, dominating the lucrative Silk Road routes. Tang armies defeated the Eastern Turks, annexed the Tarim Basin city-states, and even penetrated into present-day Afghanistan. In 751, the Tang encountered Arab armies in the famed Battle of Talas – a rare defeat that checked further westward expansion but inadvertently transmitted papermaking technology to the West. In the south, Tang vassalage extended to Tibet, Nepal, and the Korean Peninsula (Silla Korea was a Tang ally). Even distant Japan emulated Tang institutions by sending envoys and students to Chang’an. With such reach, the Tang in the 8th century was arguably the world’s most powerful empire.

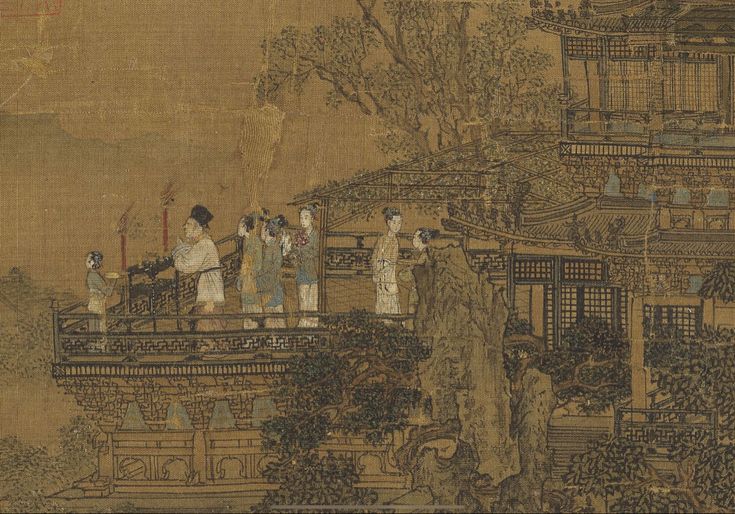

Culturally, the Tang Dynasty is synonymous with poetry. It produced China’s greatest poets: Li Bai (Li Po), whose free-spirited verses celebrate wine, friendship, and nature with transcendent imagination; Du Fu, a deeply humane poet-historian who recorded the tumult of his times with moral urgency and technical mastery; Wang Wei, the poet-painter of tranquil landscapes and Buddhist insight; and dozens more. Poetry was so essential that composing verse was part of the civil exams. The Tang era also saw flourishing of painting – especially landscape painting which became a major art form (artists like Han Gan, Wu Daozi, and later in Tang, Zhang Xuan and Zhou Fang excelled in figure and landscape paintings). Ceramics reached new heights: the famed Tang sancai (three-color) glaze pottery figurines – tomb goods of horses, camels, ladies – showcase the vibrancy of Tang artisanship. Music and dance thrived, enriched by influences from Central Asia; the imperial court had orchestras with instruments like lutes and oboes introduced via Silk Road. Chang’an’s bustling markets and pleasure quarters teemed with entertainers from as far as India and Persia, making Tang culture remarkably syncretic.

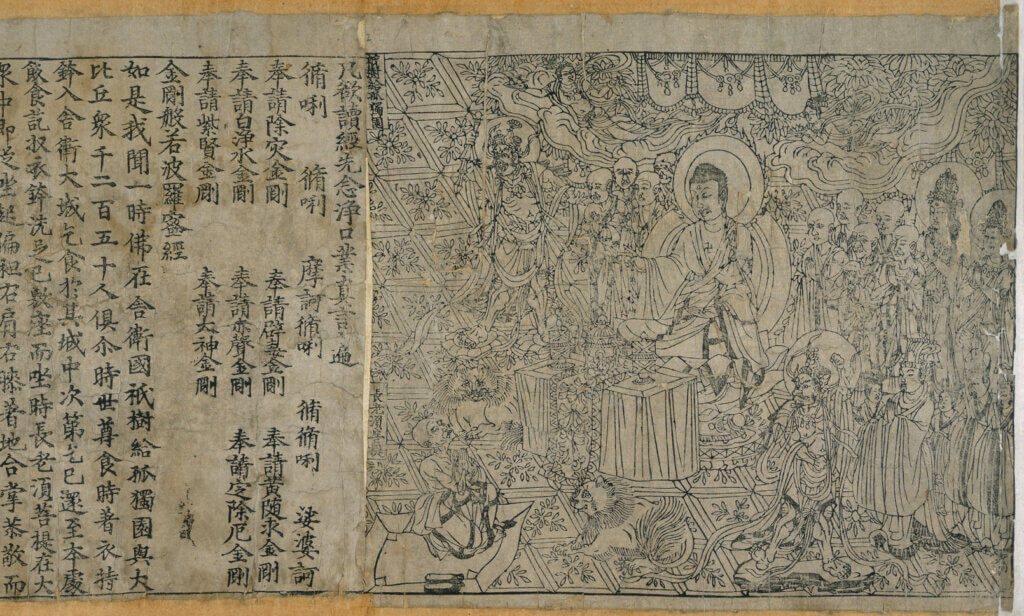

In science and technology, Tang innovators made significant contributions. Woodblock printing was invented by the 7th century and widely used by the 8th century. The oldest surviving printed book in the world, the Diamond Sutra, dates to 868 CE in Tang China. The spread of printed texts in Tang meant that literature, religious scriptures, and calendars could be reproduced and circulated more efficiently than ever before, foreshadowing the print revolution of later centuries. The fuel for printing’s development was the growing number of educated people and the demand for books (Buddhism, with its need for many sutra copies, was a big impetus). Additionally, gunpowder was first formulated during the Tang – alchemists in the 9th century mixed sulphur, saltpeter, and charcoal seeking elixirs, only to discover explosive powder. A mid-9th-century Taoist text even warns of the powder’s incendiary properties. While its military use was not fully realized until Song, gunpowder’s invention is credited to late Tang. Other advances include astronomy (Yixing, a monk-astronomer, helped produce an accurate calendar and pioneered the world’s first clockwork escapement mechanism for timing), and medicine (the Tang era medical compendium Xin Xiu Ben Cao was published in 659, and the first medical schools were established).

Religion and spirituality in Tang China were rich and varied. Buddhism reached its zenith of influence. The capital alone housed hundreds of temples and thousands of monks. Different Buddhist schools flourished: Chan (Zen) Buddhism matured during Tang (the legendary sixth patriarch Huineng died in 713), Pure Land Buddhism offering salvation by Amitabha’s grace spread among commoners, and esoteric Buddhism from India gained imperial patronage in the 8th century. The most celebrated pilgrim, Xuanzang, traveled to India in 7th century and returned with loads of scriptures, spending 19 years translating them – his journey later inspired the novel Journey to the West. However, towards the end of the dynasty, Buddhism’s wealth and foreign origins sparked backlash. In 845 CE, Emperor Wuzong infamously ordered the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution, closing thousands of monasteries, confiscating assets, and forcing monks to secularize. Although this dealt a blow, Buddhism survived and remained a major faith. Daoism also enjoyed state patronage – the Tang imperial family claimed descent from Laozi, and emperors often honored Daoist priests. Daoist alchemy and ritual continued to evolve (and interestingly contributed to discoveries like gunpowder). Confucianism saw a revival towards late Tang, not as mere state cult (which had waned in early Tang due to Buddhism’s sway) but reborn as Neo-Confucianism in embryonic form, as scholars like Han Yu (768–824) criticized Buddhism and called for a return to classical teachings, foreshadowing Song-era Neo-Confucian philosophy.

Martial culture in Tang had its legendary moment too. In approximately 621 CE, during the transition from Sui to Tang, the Tang prince Li Shimin (later Emperor Taizong) faced a warlord enemy named Wang Shichong. In the Battle of Hulao, an unlikely group of 13 Shaolin warrior monks came to Tang’s aid, reportedly rescuing Li Shimin’s life. For their service, the Shaolin Temple was granted imperial patronage and land. This is the first recorded instance of Shaolin monks in combat and marked the beginning of Shaolin’s fame as a martial monastery. Tang Taizong allegedly granted the monks an inscription praising them, and Shaolin’s fighting prowess became renowned. Later in the Tang, Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–756) is said to have established a training ground for imperial guards at Shaolin. Whether fully factual or part-legend, these stories underscore that Shaolin Temple by Tang times was firmly associated with martial skill in addition to spiritual practice.

The Tang Dynasty eventually declined due to internal strife and external pressures. The An Lushan Rebellion (755–763) – a massive revolt by a Tang general of Sogdian-Turkic origin – devastated the empire, leading to regional warlords gaining power. Despite a mid-9th century revival under capable emperors, further rebellions and eunuch domination at court weakened the dynasty. In 907 CE, the Tang state finally fragmented. Yet, the legacy of Tang endured as an idealized epoch of open-minded sophistication and might. Later generations referred to themselves as “Tang people” (tángrén 唐人) especially among overseas Chinese – a testament to Tang’s prestige. Neighboring Asian cultures (Japan, Korea, Vietnam) took heavy inspiration from Tang institutions, fashion, and arts. Even today, the Tang is fondly remembered as a pinnacle of Chinese civilization.

The Song Dynasty (Sòngcháo 宋朝, 960–1279 CE)

After several decades of fragmentation in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907–960) period, China was reunified under the Song Dynasty. The Song era (divided into Northern Song 960–1127 and Southern Song 1127–1279) was another golden age – noted more for its cultural, economic, and scientific brilliance than for military power. The Song emperors presided over a deeply civil administration, with refinements in governance and a flourishing of arts and technology that in some ways surpassed the Tang. However, they ruled a truncated China and faced strong foreign powers, which eventually conquered them.

The Northern Song, with its capital at Bianjing (Kaifeng), emerged after General Zhao Kuangyin (Emperor Taizu) usurped the last of the Five Dynasties. Learning from the Tang’s demise, the Song emperors consciously curtailed military autonomy and elevated civil officials. The army was kept under closer control of the throne, and top generals were often rotated or retired – strengthening the emperor’s hand but arguably weakening military effectiveness. The Song state is famous for its robust civil service examination system. Expanding on Tang practices, the exams became the primary route to office, open to gentry of all regions. This meritocratic system (though dominated by land-owning elites who could afford education) created a class of scholar-officials whose identity was more tied to Confucian learning than aristocratic birth. The bureaucracy was sophisticated; governance manuals and codified laws guided administrators. Song Taizu and successors improved local administration and introduced community programs (like orphanages and paupers’ cemeteries) reflecting a benevolent outlook. Fiscally, the Song had a complex taxation system and state monopolies on certain industries.

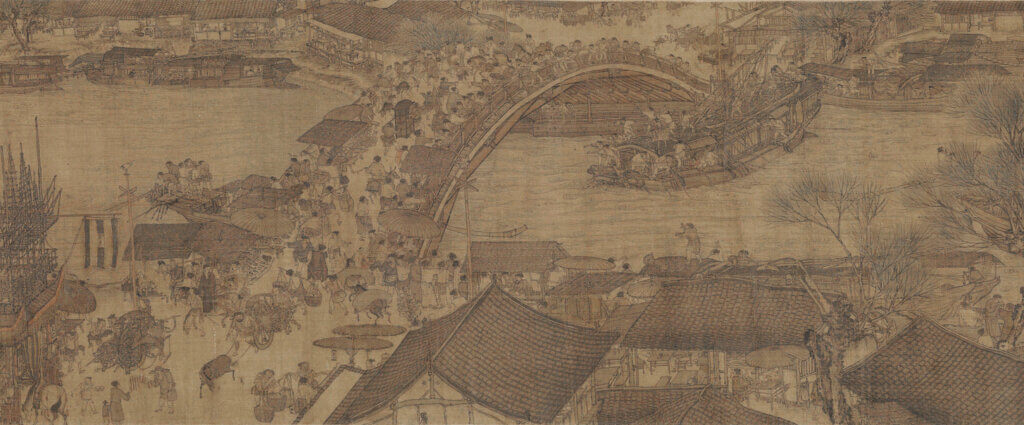

Economically, Song China experienced an unprecedented commercial boom. A remark often made: if Tang was cosmopolitan aristocratic glory, Song was urban commercial vitality. The population grew to perhaps 100 million, and cities over a million people like Kaifeng and later Hangzhou (in Southern Song) bustled with commerce. Markets were active not just by day but at night (a novelty in Kaifeng due to widespread use of oil lamps). The Song government issued the world’s earliest known paper money (jiaozi), reflecting the huge volume of trade. Trade guilds and merchant associations appeared. The Song state also invested in massive canal projects and improved the Grand Canal, integrating the economy. In a famous quote, the historian Sima Guang noted that in Song times, goods from all over the empire could be found in the markets – a tribute to integrated commerce.

Technologically, the Song Dynasty stands out as perhaps the most innovative period in pre-modern world history. Printing technology advanced from woodblock to the invention of movable type in the 11th century (pioneered by Bi Sheng around 1040 CE). Though woodblock remained dominant, movable type printing was used in large projects (e.g. printing the complete Confucian classics) and foreshadowed later printing revolutions. The widespread availability of printed books in Song meant literacy and knowledge spread even further than in Tang – there were public bookshops and libraries, and exam candidates could study printed study guides. Gunpowder weapons emerged in warfare. By mid-Southern Song, the Chinese armies fielded gunpowder bombs, flame-throwers (fire lances), and early cannons – initially to fight northern invaders. The Song navy famously used gunpowder bombs against the Jurchen and later the Mongols, making the Song military, while not victorious overall, the first to deploy guns in battle. Another major innovation was the magnetic compass, which by Song times was adapted for navigation at sea (helping merchants traverse open oceans). In mechanical engineering, Su Song, a polymath official, built an elaborate astronomical clock tower in Kaifeng in 1090 CE – complete with a water-powered escapement and rotating armillary sphere, arguably the most advanced clock in the world at that time. Irrigation and agricultural technology improved too: new rice strains from Champa (Vietnam) were introduced, allowing multiple crops a year in the south and contributing to a population boom. All these inventions had global significance: movable type and compass would later revolutionize Europe, while gunpowder changed warfare forever.

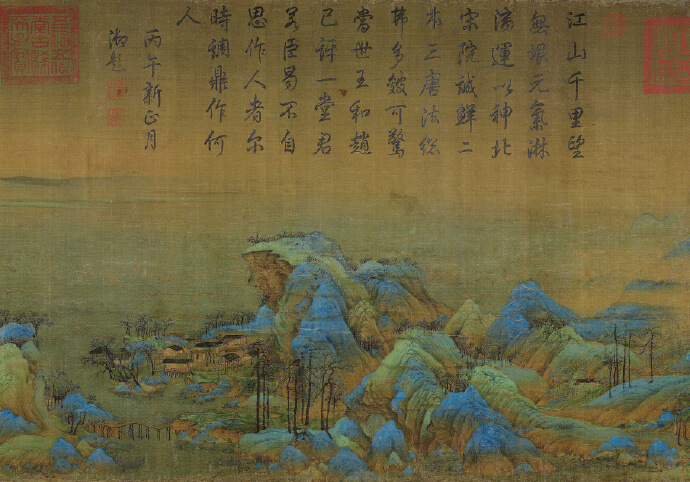

Culturally, the Song period was exceedingly rich. Scholar-officials not only governed but also pursued the arts as gentlemen’s pastimes. Painting reached sublime heights, especially landscape painting (shanshui 山水). Northern Song masters like Fan Kuan, Guo Xi, and Li Cheng created monumental scrolls depicting nature’s grandeur with precise brushwork and philosophical depth. Southern Song painters like Ma Yuan and Xia Gui employed more impressionistic techniques, capturing poetic moments of nature. Calligraphy remained a supreme art – master calligraphers like Su Shi (who was also a famed poet) and Huang Tingjian are emulated to this day. Literature saw the maturation of Ci poetry – lyric poems set to musical meters – with Song poets like Li Qingzhao (a woman poet renowned for her elegant and poignant verse) and Xin Qiji achieving mastery. Meanwhile, prose thrived in historiography and essays. Song novels had not yet bloomed (the great classical novels would come in Ming), but storytelling and theater grew popular, sowing seeds for later drama and fiction.

Philosophically, the Song Dynasty witnessed the rise of Neo-Confucianism (Lǐxué 理学). Thinkers like Zhu Xi (1130–1200) synthesized Confucian morality with metaphysics, borrowing concepts from Buddhism and Daoism, to create a refreshed Confucian ideology that addressed questions of cosmos, human nature (xing 性), and principle (li 理). Zhu Xi’s commentaries on the Four Books became the new orthodoxy for civil exams, deeply influencing education for centuries. Neo-Confucianism emphasized reason and ethics, underscoring the Confucian values of family, propriety, and righteous action in a more spiritually resonant framework. It became the intellectual hallmark of the late imperial era.

The religious landscape in Song remained diverse. Buddhism continued to be significant, though without Tang-style state sponsorship. Chan (Zen) Buddhism in particular gained many adherents among the literati – it suited their preference for personal enlightenment and had an affinity with artistic sensibilities. Some Song emperors were devout Buddhists or Daoists, but generally, the state favored a balanced tolerance. Daoism enjoyed imperial favor especially under Emperor Huizong (r. 1100–1126), who was an enthusiastic patron of Daoist alchemy and art. Popular religion also thrived – common folks combined Buddhist, Daoist, and local shamanistic practices. Notably, the Song period saw the compilation of extensive encyclopedias and compilations of knowledge (like Shen Kuo’s Dream Pool Essays, an astounding treatise touching on scientific observations from magnetic declination to fossil theory). This evidences an almost modern curiosity and empiricism among some scholars.

Despite its brilliance, the Song Dynasty had military weaknesses. The dynasty never controlled as much territory as Tang or Han; it lost the north to the Jurchen Jin Dynasty in 1127, when invaders captured Kaifeng – an event known as the Jingkang Incident. The court fled south, reestablishing as the Southern Song in Hangzhou (Lin’an). The Southern Song, though smaller, remained economically robust – in fact, its maritime trade expanded, making Song China a naval trading power. It engaged in commerce with Southeast Asia, India, and the Middle East; porcelains and tea flowed out while spices and gems came in. The world’s first true standing navy was created by the Southern Song to defend its coast and riverfront, employing advanced ships with bulkhead compartments and armed with trebuchets and early firearms.

Finally, however, the Song succumbed to the rise of the Mongols. The Mongol Empire under Genghis Khan and his heirs conquered the Jin in the north and then turned on the Southern Song. After decades of struggle, the last Song stronghold fell in 1279 at the Battle of Yamen, where a loyal minister clasped the boy-emperor and leapt into the sea to their deaths – an image immortalizing the Song’s Confucian loyalty unto extinction. Despite this tragic end, the Song Dynasty’s legacy is immense. It was a time of brilliant culture and momentous innovation, as well as the solidification of societal structures (like the exam system and Neo-Confucian social norms) that would guide China in subsequent eras. Chinese often look back at Song as a peak of refinement: prosperous cities, elegant scholars, scientific spark, and exquisite art – a civilization shining internally, even if it failed to dominate its enemies externally.

A Song Martial Arts Primer

The Song era, while dominated by scholarly culture, also contributed to martial arts in subtle ways. The collapse of aristocratic power and rise of the citizen-soldier meant martial traditions became more grassroots. General Yue Fei, a Southern Song patriot, became a posthumous symbol of martial loyalty. Legends credit Yue Fei with creating Eagle Claw and Xingyi martial arts, and he is often venerated in martial folklore (whether he truly created those arts is debatable, but his patriotism and reputed strength inspired later warriors). The Song military compiled extensive martial knowledge: for example, the Wujing Zongyao (1044) was a military encyclopedia that detailed weapon designs (including formulas for gunpowder). Late Song also saw the earliest known martial arts manual: General Qi Jiguang’s writings (actually Ming, but he referenced older practices) included routines that likely originated from Song or earlier military training. Additionally, wrestling (shuai jiao) was popular at the Song court; Emperor Huizong even wrote about wrestling techniques. Finally, the notion of wushu as a civilian skill took hold: with many soldiers demobilized after wars, some made livelihoods as martial arts instructors or bodyguards, transmitting skills that would later feed into Ming-Qing era martial arts societies.