In part two of our blog series, “Debunking the Myths of Kung Fu in China,” we delve into the impact of “New China” on the traditions and teachings of Shaolin kung fu, continuing the discussion introduced in our recent publication with Martial Arts Magazine Australia, Issue 6 (see Part 1 here). This section, “How Did the Rise of New China Affect Shaolin Kung Fu?” examines how evolving sociopolitical landscapes have influenced both the philosophy and practice of this ancient art.

Today, Shaolin kung fu stands as a bridge between China’s cultural heritage and its dynamic modernity. As a long-term student at Maling Shaolin Kung Fu Academy, I’ve observed firsthand how these transformations are woven into our daily practice under the guidance of Master Shi Xing Jian. Through his perspective and with translation support from our academy administrator Lisa Guo, we explore how Shaolin’s principles have adapted in response to New China’s influence—without losing the essence that defines true Shaolin kung fu.

How did the rise of new China affect Shaolin kung fu?

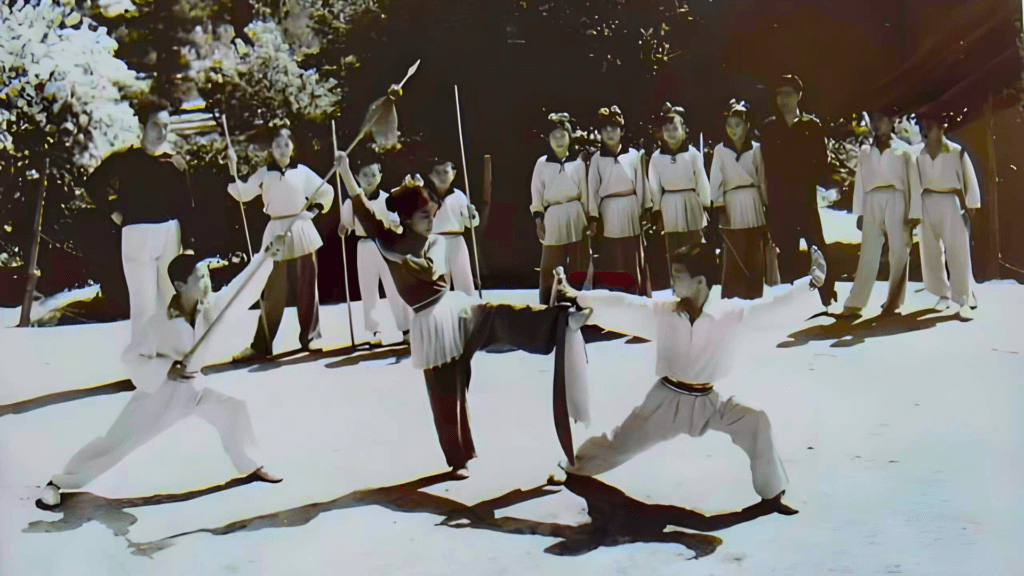

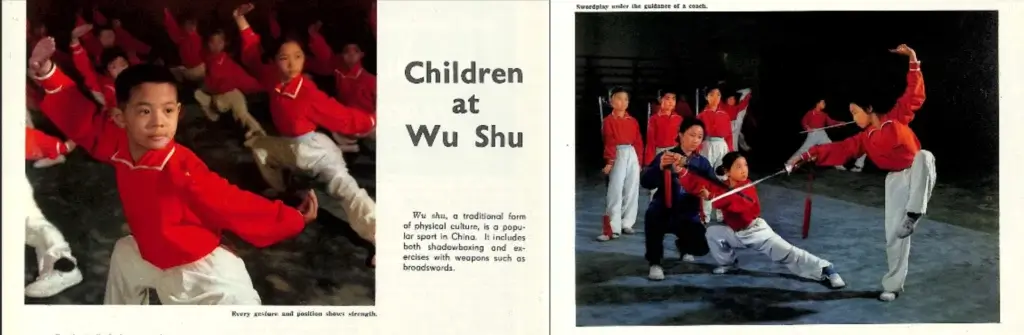

Contrary to popular belief, the establishment of New China under the Communist government did not suppress Shaolin kung fu or Chinese martial arts. In fact, the government became a strong supporter of wushu and martial arts in general. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, national policies actively promoted wushu, even forming a national wushu team to showcase the country’s martial prowess. All styles of Chinese martial arts, including Shaolin, benefitted from this institutional support, which fostered both traditional and modern forms of martial practice.

However, a myth persists in some circles: that kung fu masters fled China due to political persecution and government attacks on their practices. This is simply untrue. The real reasons for the migration of martial arts masters were more complex and economic in nature. At the turn of the 20th century, China was going through major technological and societal shifts. The invention and rise of firearms—referred to as ‘hot weapons’—diminished the need for martial arts in warfare. Where once a master skilled in techniques like the iron palm could overpower an enemy, no amount of hand-to-hand combat could compete with a bullet. As a result, the relevance of martial arts in combat began to decline, leading to a period where the art, while still respected, had less practical application.

By the early 1900s, during the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, China was rife with upheaval. Many martial masters faced economic challenges, not political ones. Without a need for their skills in the military or self-defense, some left the country seeking better opportunities abroad. This exodus was less about escaping government oppression and more about finding ways to support themselves and preserve their arts in an evolving world.

The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), however, did bring a brief but significant period of turmoil for traditional practices, including martial arts. Originally supported by the country’s leader (though, once its devastating effects were demonstrated he no longer favored the reform), the Revolution was initially intended to speed up China’s development by purging the country of outdated and harmful traditions. The government sought to create a new socialist culture, and young revolutionaries, known as the Red Guards, took radical measures to destroy anything they deemed part of the “old ways”—temples, shrines, historical architecture, and even traditional practices like kung fu were targeted.

The motivation behind these attacks wasn’t anti-kung fu, specifically; it was a broader rejection of tradition in favor of progress. So, aside from the obvious economic reasons, why were so many youths against tradition and heritage? Many saw old customs as dangerous and unscientific. For example, in ancient times, if a child fell seriously ill, many families would turn to temples and pray for divine intervention rather than seeking medical care. These beliefs carried through the generations, creating a culture of superstitious neglect, ignorance, and rejection of modern, safe, life-saving practices. These outdated beliefs were seen as obstacles to modernizing China and harmful to upcoming generations. And so, revolutionaries sought to tear down the physical and cultural symbols of the past to force the country to move forward.

In this climate, traditional martial arts—including Shaolin—suffered. Kung fu masters, along with professionals from many other fields, were caught up in the sweeping anti-tradition fervor. Schools closed, temples were destroyed, and martial arts training went underground. The Shaolin Temple itself was largely abandoned, and many of its monks were scattered, though not permanently.

Despite this period of cultural destruction, martial arts in China endured. After the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, and particularly during the economic reforms of the 1980s, martial arts experienced a resurgence. The government again became a strong advocate of wushu, both modern and traditional, and encouraged its practice among the general populace. Shaolin kung fu, too, saw a revival. The rebuilding of the Shaolin Temple and the growing international interest in Chinese martial arts helped fuel this renaissance, leading to the global recognition Shaolin enjoys today.

It is important to understand that the persecution of traditional martial arts during the Cultural Revolution was not an intentional attack on kung fu specifically but a byproduct of broader anti-traditionalist sentiments. In the years since, the Chinese government has actively worked to preserve and promote Chinese martial arts as a vital part of its cultural heritage, allowing Shaolin and other arts to thrive once again.

Want To Read More?

Check out Part 1 and stay tuned in the coming weeks for the last section of the article! If you live in Australia and want to support the magazine, check out the digital or printed copy of Martial Arts Magazine Australia (MAMA), Issue 6 on their website.

Disclaimer: We do not receive any financial compensation from the sales or distribution of Martial Arts Magazine Australia, Issue 6, which features the referenced article. Our sole intent is to share our contribution to this publication with our readers.