The Shaolin Temple, nestled in the Songshan Mountains of China, is revered not only as the birthplace of Chan (Zen) Buddhism but also as the cradle of Chinese martial arts, particularly Shaolin Kung Fu. The philosophies and practices within the Shaolin Temple are a unique blend of Buddhist teachings, martial discipline, and ethical conduct. These traditions have been preserved and passed down through centuries, creating a rich cultural and spiritual heritage. This article delves into the various philosophies, precepts, virtues, and the distinctive roles of the wuseng (warrior monks) and wenseng (scholar monks) within the Shaolin Temple.

Core Philosophies of the Shaolin Temple

The Shaolin Temple’s philosophy is deeply rooted in Chan Buddhism, which emphasizes meditation, mindfulness, and direct experience of one’s true nature. This approach fosters a balance between spiritual cultivation and practical, everyday living. The monks of Shaolin believe that physical training and martial arts are not merely exercises but integral to spiritual growth. The physical discipline required in martial arts mirrors the mental discipline necessary in meditation, leading to a harmonious development of body and mind.

Shaolin philosophy is encapsulated in the concept of Wǔdé (武德), or “martial virtue,” which underscores the ethical framework guiding the practice of martial arts. Wǔdé promotes qualities such as humility, respect, righteousness, trust, and loyalty. The idea is that martial skills should be used only for self-defense and to protect the weak, never for personal gain or aggression. This moral compass ensures that the power acquired through martial training is tempered by a deep sense of responsibility and compassion.

Virtues and Precepts: The Moral Foundations

The Shaolin Temple emphasizes a strict code of ethics and virtues that guide the lives of its monks. These virtues and precepts form the foundation of their spiritual practice and are integral to their daily lives. Below are some of the key virtues and precepts upheld at the Shaolin Temple:

1. The Five Precepts (五戒, Wǔ Jiè)

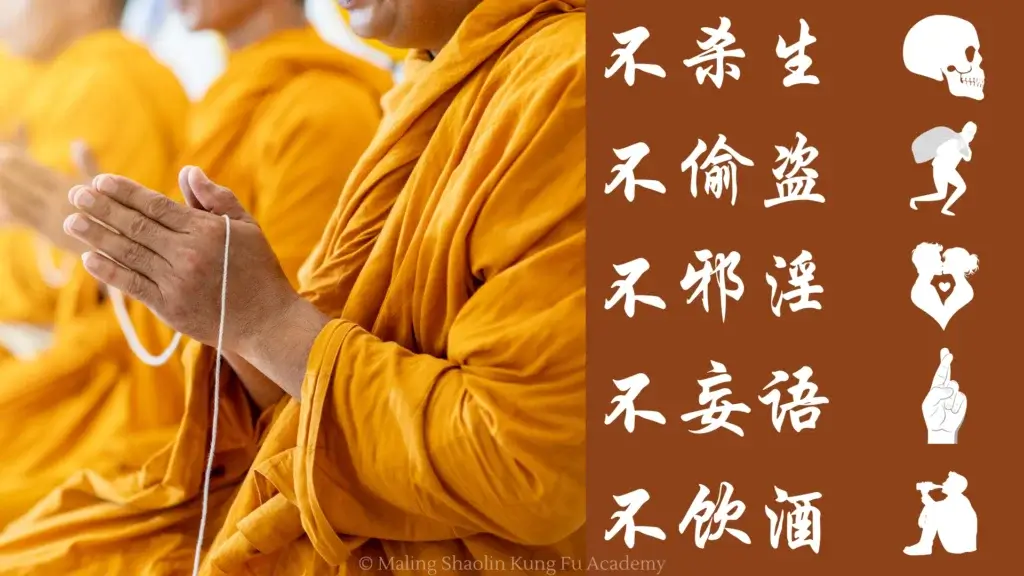

The Five Precepts are fundamental ethical guidelines in Buddhism that Shaolin monks strictly adhere to. As you will note below, they are the foundation for most other moral precepts. They are:

- No Killing (不杀生, Bù Shāshēng): Monks vow to respect all forms of life and refrain from taking the life of any living being. This precept aligns with the principle of ahimsa (nonviolence), which is central to Buddhist practice. Even though Shaolin monks practice martial arts, they do so with the understanding that their skills are for self-defense and protection, not for harming others.

- No Stealing (不偷盗, Bù Tōudào): Monks are forbidden from taking anything that is not freely given to them. This precept teaches contentment and respect for others’ property.

- No Sexual Misconduct (不邪淫, Bù Xiéyín): Monks take a vow of celibacy, refraining from any form of sexual activity. This precept encourages purity of mind and body, helping monks focus on their spiritual practice.

- No Lying (不妄语, Bù Wàngyǔ): Honesty is a crucial virtue for monks, who are expected to speak truthfully at all times. This precept fosters trust and integrity within the monastic community.

- No Intoxicants (不饮酒, Bù Yǐnjiǔ): Monks abstain from alcohol and drugs, as these substances can cloud the mind and hinder spiritual development. Maintaining a clear and focused mind is essential for meditation and martial arts practice.

2. The Ten Grave Precepts (十重戒, Shí Zhòng Jiè)

In addition to the Five Precepts, Shaolin monks follow the Ten Grave Precepts, which are more comprehensive ethical guidelines that cover a broader range of conduct. They serve as a moral compass for monastic and lay practitioners, guiding their behavior and helping them avoid actions that could lead to harm or suffering for themselves or others:

- Not Killing (不杀生, Bù shā shēng)

- Refrain from taking life in any form, whether human or animal.

- Not Stealing (不偷盗, Bù tōu dào)

- Avoid taking anything that is not freely given.

- Not Committing Sexual Misconduct (不邪淫, Bù xié yín)

- Abstain from engaging in improper sexual behavior, which includes adultery, promiscuity, and any sexual activity that causes harm.

- Not Lying (不妄语, Bù wàng yǔ)

- Do not speak falsehoods or deceive others through dishonesty.

- Not Dealing in Intoxicants (不酤酒, Bù gū jiǔ)

- Avoid selling or handling intoxicants, as they cloud the mind and lead to heedlessness.

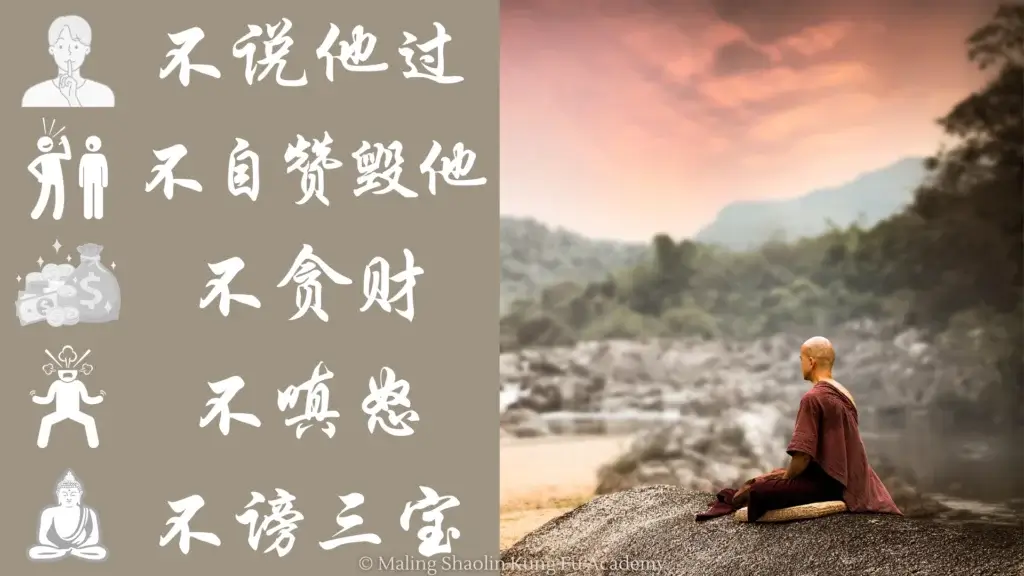

- Not Speaking of Others’ Faults (不说他过, Bù shuō tā guò)

- Refrain from gossiping or criticizing others, as it fosters division and negativity.

- Not Praising Oneself or Disparaging Others (不自赞毁他, Bù zì zàn huǐ tā)

- Do not boast about your own virtues or accomplishments while belittling others, which breeds arrogance and jealousy.

- Not Hoarding Wealth (不贪财, Bù tān cái)

- Avoid accumulating excessive wealth or material possessions, as attachment to them can lead to greed and suffering.

- Not Giving in to Anger (不嗔怒, Bù chēn nù)

- Refrain from harboring or expressing anger, which is a destructive emotion that causes harm to oneself and others.

- Not Defaming the Three Treasures (Buddha, Dharma, Sangha) (不谤三宝, Bù bàng sān bǎo)

- Do not speak ill of the Buddha, Dharma, or Sangha, as doing so shows disrespect to the foundational aspects of Buddhist practice.

3. The Ten Precepts for Novice Monks (沙弥十戒, Shāmí Shí Jiè)

The Ten Precepts for Novice Monks (沙弥十戒, Shāmí Shí Jiè) are specific to Buddhist monastic practices, particularly for novice monks. These precepts are more strict than the general Ten Grave Precepts because they are intended to instill discipline and a foundation of moral behavior in novice monks:

- First Precept (第一戒, Dì Yī Jiè): Not to Kill (不杀生, Bù Shā Shēng)

- Briefly: Do not kill any sentient beings.

- Second Precept (第二戒, Dì Èr Jiè): Not to Steal (不偷盗, Bù Tōu Dào)

- Briefly: Do not take what is not given, without the owner’s permission.

- Third Precept (第三戒, Dì Sān Jiè): Not to Engage in Sexual Misconduct (不非梵行, Bù Fēi Fàn Xíng)

- Briefly: Do not engage in sexual activities, whether with humans or non-humans.

- Fourth Precept (第四戒, Dì Sì Jiè): Not to Lie (不妄语, Bù Wàng Yǔ)

- Briefly: Do not speak falsely, especially the great lies—claiming spiritual attainments that one has not achieved.

- Fifth Precept (第五戒, Dì Wǔ Jiè): Not to Consume Intoxicants (不饮酒, Bù Yǐn Jiǔ)

- Briefly: Do not consume intoxicating substances, including alcohol, drugs, and other mind-altering substances.

- Sixth Precept (第六戒, Dì Liù Jiè): Not to Adorn Oneself with Garlands, Perfumes, or Cosmetics (不著华鬘好香涂身, Bù Zhāo Huá Mán Hǎo Xiāng Tú Shēn)

- Briefly: Do not dress elaborately or apply luxurious perfumes, oils, or cosmetics to your body.

- Seventh Precept (第七戒, Dì Qī Jiè): Not to Engage in Singing, Dancing, or Entertainment (不歌舞观听, Bù Gē Wǔ Guān Tīng)

- Briefly: Do not watch or listen to singing, dancing, drama, or similar forms of entertainment.

- Eighth Precept (第八戒, Dì Bā Jiè): Not to Sit on High or Luxurious Beds or Seats (不坐高广大床上, Bù Zuò Gāo Guǎng Dà Chuáng Shàng)

- Briefly: Do not sit in elevated positions (such as leadership seats) or on large, luxurious beds.

- Ninth Precept (第九戒, Dì Jiǔ Jiè): Not to Eat After Noon (不非时食, Bù Fēi Shí Shí)

- Briefly: Also known as “not eating after noon,” which means not consuming food after midday.

- Tenth Precept (第十戒, Dì Shí Jiè): Not to Handle Money or Valuables (不捉钱金银宝物, Bù Zhuō Qián Jīn Yín Bǎo Wù)

- Briefly: Do not own, seek, or hoard money, jewels, or other valuables.

These precepts are a core part of monastic discipline, designed to guide novice monks in their spiritual journey, helping them cultivate virtues such as self-restraint, humility, and mindfulness. This set of rules is stricter than the Ten Grave Precepts because it is specifically tailored for those on the path to becoming fully ordained wenseng monks.

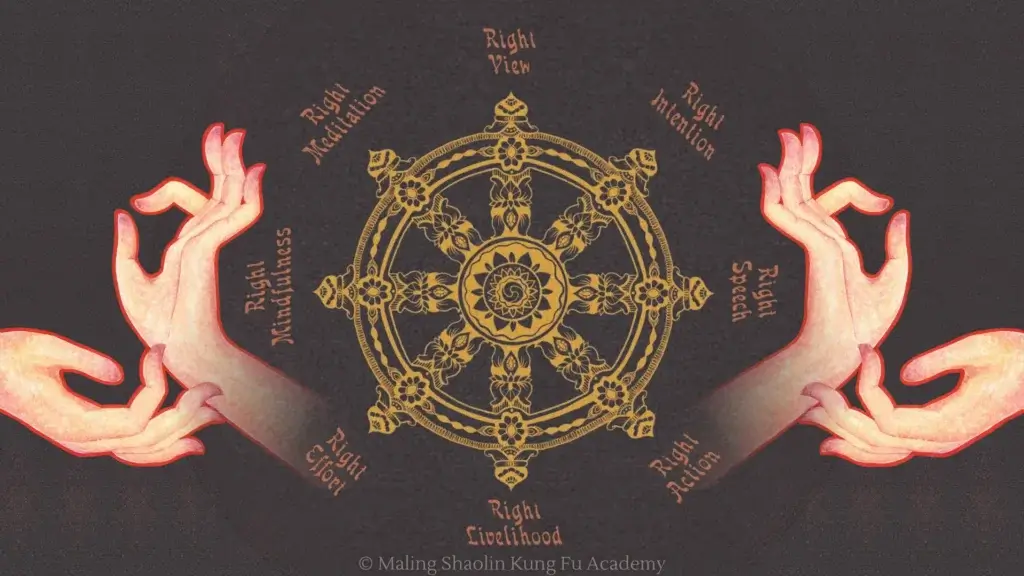

4. The Eightfold Path (八正道, Bā Zhèng Dào)

The Eightfold Path is a central tenet of Buddhist philosophy and is actively practiced by Shaolin monks. It consists of:

- Right Understanding (正见, Zhèngjiàn): Understanding the nature of reality and the path to enlightenment.

- Right Intention (正思维, Zhèngsīwéi): Cultivating intentions of renunciation, goodwill, and harmlessness.

- Right Speech (正语, Zhèngyǔ): Speaking truthfully, kindly, and wisely.

- Right Action (正业, Zhèngyè): Acting ethically and morally in all situations.

- Right Livelihood (正命, Zhèngmìng): Choosing a way of life that does not harm others.

- Right Effort (正精进, Zhèngjīngjìn): Making a sustained effort to cultivate wholesome qualities and abandon unwholesome ones.

- Right Mindfulness (正念, Zhèngniàn): Maintaining awareness of body, mind, and feelings.

- Right Concentration (正定, Zhèngdìng): Developing deep concentration through meditation.

5. Martial Virtue (武德, Wǔdé)

The concept of Wǔdé (武德) or Martial Virtue encompasses a broad range of ethical guidelines and principles that extend beyond the basic values of humility, respect, and self-control traditionally associated with martial arts. Wǔdé is deeply rooted in the philosophy of cultivating both external and internal harmony. It is divided into two key aspects: morality of deed and morality of mind.

Morality of Deed refers to the ethical principles that govern social relationships and interactions with others. These include:

- Humility (谦虚 Qiānxū): Acknowledging one’s limitations and maintaining a modest attitude, avoiding arrogance, and showing respect for others.

- Sincerity (诚实 Chéngshí): Being genuine and truthful in one’s words and actions, ensuring that there is consistency between one’s intentions and behavior.

- Politeness (礼貌 Lǐmào): Demonstrating respect and courtesy towards others, fostering harmonious interactions through good manners.

- Loyalty (忠诚 Zhōngchéng): Remaining steadfast and faithful to one’s principles, commitments, and relationships, whether to a teacher, family, or community.

- Trust (信任 Xìnrèn): Building and maintaining mutual confidence and reliability in relationships, essential for cooperation and unity.

Morality of Mind focuses on internal cultivation, balancing the emotional and wisdom aspects of the self. It includes:

- Courage (勇气 Yǒngqì): Facing challenges, dangers, and fears with confidence and bravery, whether in combat or in life.

- Patience (耐心 Nàixīn): Developing the ability to endure difficulties and delays without frustration, maintaining composure and determination.

- Endurance (坚忍 Jiānrěn): The capacity to withstand hardship, pain, and adversity over time, pushing through challenges with unwavering resolve.

- Perseverance (坚持 Jiānchí): Continuously striving towards goals despite obstacles, showing persistent effort and dedication to improvement.

- Will (意志 Yìzhì): The strength of mind to control impulses, stay focused, and remain committed to one’s purpose and principles.

The ultimate aim of Wǔdé is to achieve Wuji (无极), a state of balance and harmony where wisdom and emotions are aligned, leading to a life of inner peace and ethical integrity. This concept is closely tied to wu wei (无为), the Taoist principle of effortless action, where one moves in harmony with the natural flow of life, without force or resistance.

These virtues are integral to the philosophy of the Shaolin Temple and serve as a moral compass for both wúsēng (warrior monks) and wénsēng (scholar monks). While wúsēng may have different lifestyles, the core values of Wǔdé remain consistent across all practitioners, guiding their conduct both in martial practice and daily life. The emphasis on these virtues reflects the belief that martial arts are not merely physical disciplines but also spiritual paths that cultivate character and morality.

6. Compassion (慈悲, Cíbēi)

Compassion (Cíbēi), in the context of martial arts, is the profound and active expression of empathy, kindness, and love towards others. It is not merely an emotion but a virtue that encourages action to alleviate the suffering of others and contribute positively to society. In traditional Chinese philosophy and martial arts, compassion is seen as a fundamental principle that guides a martial artist’s conduct both in and out of the training hall.

1. Philosophical Roots of Compassion

Compassion is deeply intertwined with the teachings of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, all of which have influenced martial arts philosophy.

- Confucianism emphasizes the importance of Ren (仁), often translated as “benevolence” or “humaneness,” which is a form of compassion directed towards others. A martial artist is expected to show Ren by treating others with kindness and consideration, fostering harmony in relationships and society.

- Buddhism teaches the concept of Karuna (compassion), where a practitioner strives to alleviate the suffering of all sentient beings. In martial arts, this translates into the idea that one’s skills should never be used for unnecessary violence but rather for protection and justice.

- Taoism advocates for living in harmony with the Tao (the Way), which includes a deep sense of connection and empathy with all living things. Compassion in this sense is about understanding the interconnectedness of life and acting in ways that preserve balance and peace.

2. Compassion in Martial Practice

In the martial arts context, compassion manifests in various ways:

- Restraint in Combat: A martial artist is trained to defend, not to harm unnecessarily. The principle of compassion guides practitioners to avoid violence whenever possible, using their skills primarily for self-defense or the protection of others. This also involves exercising restraint and showing mercy when faced with an opponent, ensuring that they do not inflict more harm than necessary.

- Guidance and Teaching: Compassion is reflected in the way martial artists interact with their students, peers, and juniors. An experienced martial artist is expected to share knowledge generously, mentor others, and support the growth of their fellow practitioners. This creates a nurturing environment where students feel valued and encouraged.

- Community Service: Martial arts training often includes a commitment to serving the community. This can take the form of charity work, helping those in need, or using one’s martial skills for community safety. Such actions are direct expressions of compassion, contributing to the well-being of society.

3. Cultivating Compassion

Compassion is not only about how one interacts with others but also about how one cultivates a compassionate heart through personal practice.

- Meditation and Mindfulness: Many martial arts include meditation practices that help cultivate a compassionate mindset. Through meditation, practitioners learn to develop empathy and understanding, fostering an inner peace that extends outward to others.

- Self-Compassion: A martial artist must also practice compassion towards themselves. This means recognizing and accepting one’s limitations, treating oneself with kindness, and maintaining a healthy balance between self-discipline and self-care. Self-compassion is essential for long-term growth and well-being in the martial arts journey.

4. Compassion as a Guiding Principle

Compassion, as a guiding principle, helps martial artists make ethical decisions. Whether in the heat of combat or in everyday life, a martial artist guided by compassion seeks to act in ways that minimize harm and promote the greater good. It is a reminder that martial arts are not just about physical prowess but also about moral integrity and the betterment of humanity.

By emphasizing compassion, martial arts transcend mere physical practice, evolving into a path of ethical living where practitioners strive to bring peace, not only through their actions but also through their intentions and inner state of being.

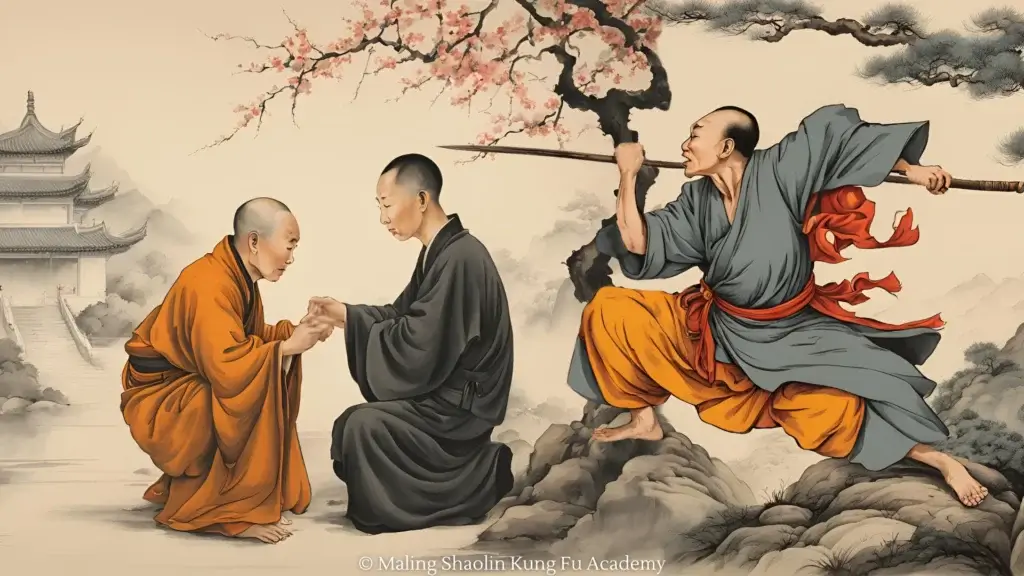

Distinctive Roles: Wuseng (Warrior Monks) vs. Wenseng (Scholar Monks)

Within the Shaolin Temple, the monks are divided into two main groups based on their focus: the wuseng (warrior monks) and the wenseng (scholar monks). While both groups share the same core Buddhist beliefs, their daily lives, responsibilities, and practices differ significantly.

Wuseng (武僧) – “Warrior Monks“

The wuseng are the guardians of Shaolin’s martial arts heritage. They engage in intense physical training, mastering various forms of Shaolin Kung Fu, weapons, and self-defense techniques. Their practice is not solely about developing physical strength but is deeply intertwined with spiritual growth. The rigorous discipline required in martial arts helps the wuseng cultivate virtues like patience, perseverance, and inner peace.

The wuseng observe Buddhist precepts but with more flexibility compared to the wenseng. For example, while vegetarianism is a common practice among wenseng, some wuseng may consume meat to maintain their physical strength. Similarly, wuseng may marry, reflecting a less ascetic lifestyle. Despite these differences, wuseng are still deeply committed to the moral principles of Buddhism and Wǔdé, ensuring that their martial prowess is always balanced with ethical conduct.

Wenseng (文僧) – “Scholar Monks“

In contrast, the wenseng focus on spiritual cultivation, meditation, and scholarly pursuits. Their lives are centered around the study of Buddhist scriptures, chanting, and the practice of meditation. The wenseng adhere strictly to traditional Buddhist precepts, such as celibacy, vegetarianism, and renunciation of worldly pleasures. Their goal is to achieve spiritual enlightenment and to guide others on the path of Dharma.

The wenseng embody virtues such as wisdom, patience, and deep compassion. Their role within the temple is to preserve and transmit the teachings of Buddhism, often serving as spiritual guides and teachers both within the temple and in the wider community.

Integrated Practice: The Synergy of Body and Mind

A unique aspect of the Shaolin Temple’s philosophy is the integration of physical and spiritual practices. The wuseng and wenseng represent two sides of the same coin, both contributing to the holistic development of the monks. The wuseng‘s martial arts training is a form of moving meditation, where the focus is on aligning the body, breath, and mind. This practice enhances mindfulness and cultivates a deep sense of presence.

The wenseng‘s contemplative practices, on the other hand, provide the mental clarity and wisdom that inform the ethical use of martial skills. By balancing these two approaches, Shaolin monks strive to achieve harmony between body and mind, realizing the ultimate goal of Chan Buddhism: enlightenment.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Shaolin Philosophy

The philosophies and practices of the Shaolin Temple have left an indelible mark on both martial arts and Buddhist traditions. The integration of physical training and spiritual discipline creates a holistic approach to personal development that has been admired and emulated around the world. Whether through the martial prowess of the wuseng or the spiritual wisdom of the wenseng, the Shaolin Temple continues to inspire generations of practitioners, offering a path to both physical mastery and inner peace. The temple’s unique blend of Chan Buddhism and martial arts remains a powerful example of how the cultivation of body and mind can lead to a life of virtue, discipline, and compassion.

Of course. What information are you looking for? Feel free to ask here or send us an email to info@shaolin-kungfu.com