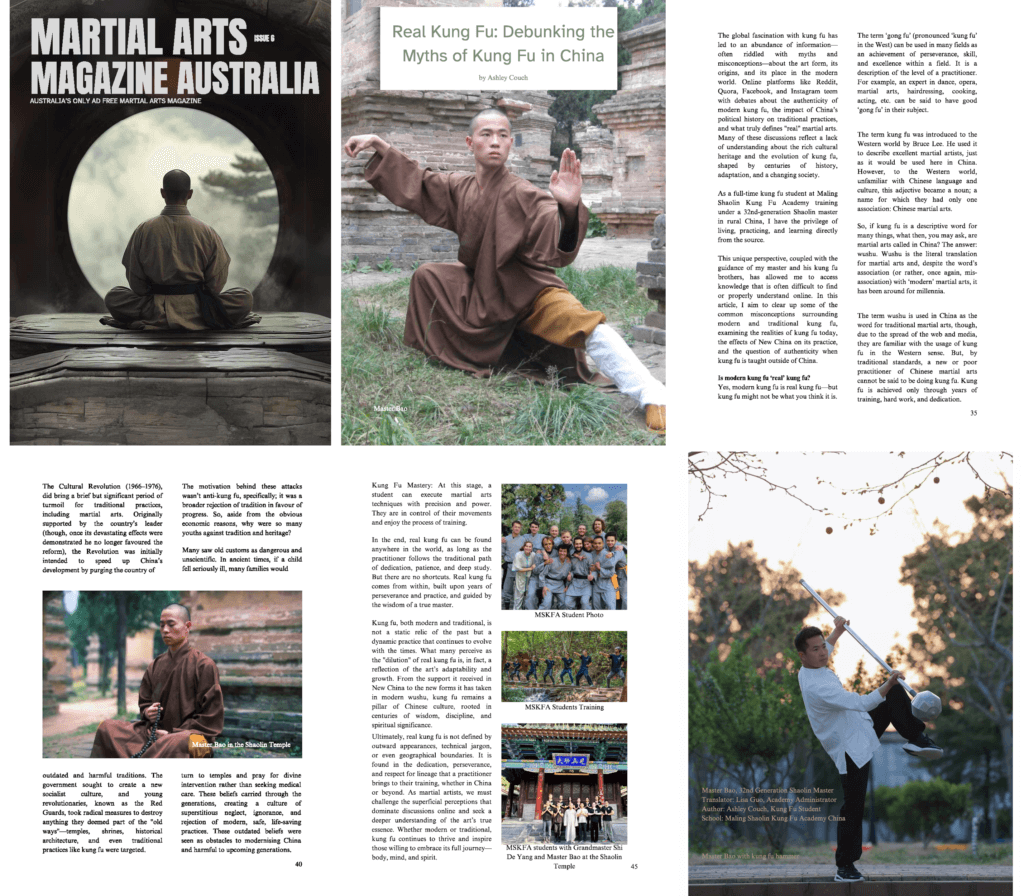

We’re excited to share a series of insights into the essence of modern Shaolin kung fu, as recently published in Martial Arts Magazine Australia, Issue 6. This series will be presented in three parts and explore some of the most pressing questions martial artists face today, relayed by a current long-term student of the school with insights from Master Shi Xing Jian and translated by Maling Academy administrator Lisa Guo:

The global fascination with kung fu has led to an abundance of information—often riddled with myths and misconceptions—about the art form, its origins, and its place in the modern world. Online platforms like Reddit, Quora, Facebook, and Instagram teem with debates about the authenticity of modern kung fu, the impact of China’s political history on traditional practices, and what truly defines “real” martial arts. Many of these discussions reflect a lack of understanding about the rich cultural heritage and the evolution of kung fu, shaped by centuries of history, adaptation, and a changing society.

As a full-time kung fu student at Maling Shaolin Kung Fu Academy training under a 32nd-generation Shaolin master in rural China, I have the privilege of living, practicing, and learning directly from the source. This unique perspective, coupled with the guidance of my master and his kung fu brothers, has allowed me to access knowledge that is often difficult to find or properly understand online. In this article, I aim to clear up some of the common misconceptions surrounding modern and traditional kung fu, examining the realities of kung fu today, the effects of New China on its practice, and the question of authenticity when kung fu is taught outside of China.

The first part of the series opens with a critical look at the term “real” kung fu, dissecting the roots, cultural shifts, and adaptations that shape contemporary practices. We aim to shed light on the misunderstandings surrounding modern kung fu and the ways it continues to embody the traditional essence of Shaolin kung fu.

Is modern kung fu ‘real’ kung fu?

Yes, modern kung fu is real kung fu—but kung fu might not be what you think it is. The term ‘gong fu’ (pronounced ‘kung fu’ in the West) can be used in many fields as an achievement of perseverance, skill, and excellence within a field. It is a description of the level of a practitioner. For example, an expert in dance, opera, martial arts, hairdressing, cooking, acting, etc. can be said to have good ‘gong fu’ in their subject.

The term kung fu was introduced to the Western world by Bruce Lee. He used it to describe excellent martial artists, just as it would be used here in China. However, to the Western world, unfamiliar with Chinese language and culture, this adjective became a noun; a name for which they had only one association: Chinese martial arts.

So, if kung fu is a descriptive word for many things, what then, you may ask, are martial arts called in China? The answer: wushu. Wushu is the literal translation for martial arts and, despite the word’s association (or rather, once again, mis-association) with ‘modern’ martial arts, it has been around for millennia.

The term wushu is used in China as the word for traditional martial arts, though, due to the spread of the web and media, they are familiar with the usage of kung fu in the Western sense. But, by traditional standards, a new or poor practitioner of Chinese martial arts cannot be said to be doing kung fu. Kung fu is achieved only through years of training, hard work, and dedication.

You may also be wondering how they differentiate, then, between ‘traditional’ martial arts and ‘modern’ martial arts (or what we in the West have dubbed wushu). There is no separate word for it. Wushu is wushu, and kung fu is excellence in wushu (and other categories). A school is known to focus on more traditional styles only by visitation, reputation, and a few other potential signifiers. Prospective students and parents may be able to tell from the name—traditional style schools may have the master or family name in the school’s name. ‘Modern’ style schools typically have a much larger number of students while ‘traditional’ schools tend to be smaller.

However, the view within China of ‘modern’ martial arts is vastly different than that of the West. Where online forums and comments frequented by Westerners often perpetuate the idea that wushu (often specifically Shaolin) isn’t ‘real,’ is diluted, is government-controlled, etc., Chinese practitioners, including Shaolin monks, think it has only improved. These varying ideals may come from different understandings of the purpose, evolution, and cultural impact of the arts. For the sake of simplicity, we will specifically discuss Shaolin going forward.

In the West, Shaolin is often viewed in a romanticized or archaic light. The general public tends to think of epic battles, meditation under waterfalls, mountain-top temples, superhuman strength, or even mystical abilities. It can be incorrectly viewed as a static link to a bygone era. This doesn’t necessarily apply only to foreigners. In China, starry-eyed youths and those far removed from the influence of wushu also sometimes have a warped view of Shaolin based on movies, legends, and media.

Practitioners, and much of the general public in China, typically view martial arts, including Shaolin, in a few ways: 1) as a method of self-betterment, whether that be physical or spiritual; 2) as a functional form of self-defense; 3) as a sport. Shaolin’s original purpose has continually evolved over the centuries, from serving as a means to protect the temple and refugees during times of war, to a meditative and spiritual practice used to help oneself along the path to Enlightenment, to a form of acrobatic enthrallment and physical transcendence. It is seen to be ever-changing, adjusting itself to the needs of society and its devotees. After all, the rest of the world changes, why shouldn’t Shaolin?

Now, how do Shaolin masters view the changes that have taken hold of much of the martial arts in China? First, I will introduce Master Bao, Buddhist name Shi Xing Jian, a 32nd-generation Shaolin warrior monk, under the esteemed lineage of Grandmaster Shi De Qian and Grandmaster Shi De Yang. Master Bao grew up training in the original Shaolin Temple and has dedicated his life to sharing the culture and excellence of Shaolin kung fu with the world. So, what are his thoughts on the matter?

I interviewed Master Bao for his valuable insight into the subject (and much of the content from the rest of this article). His perspective on the current state of kung fu offers a nuanced view of the ongoing debate about traditional versus modern martial arts.

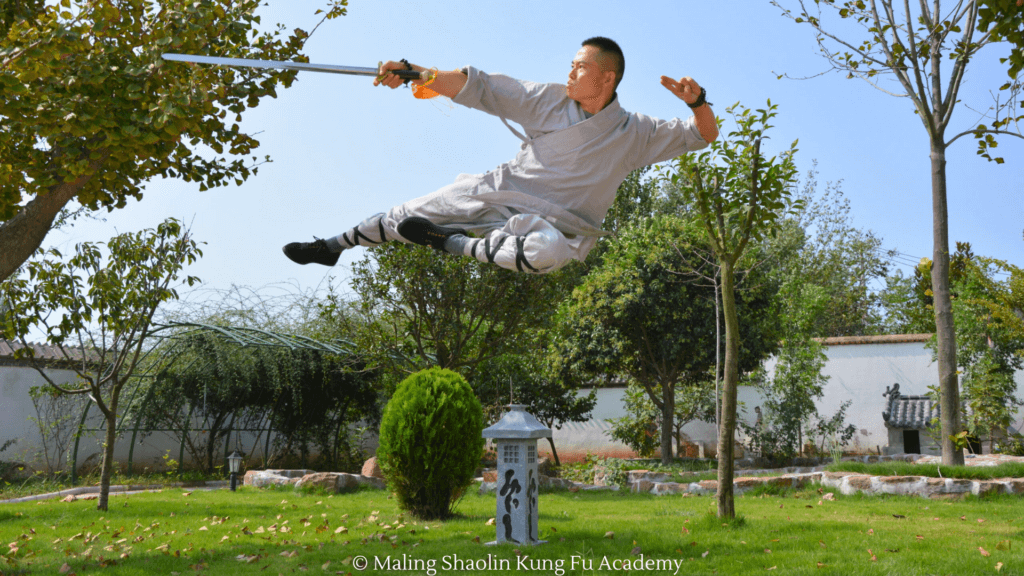

When asked about ‘modern’ wushu, Master Bao’s response was clear: it is excellent practice, and in some ways, it can be even more challenging than traditional wushu. The reason is that modern wushu incorporates visually striking elements—deeper stances, faster movements, and higher jumps—that demand greater physical agility, muscle power, and flexibility. These exaggerated movements, while sometimes criticized for their focus on aesthetic beauty, actually help practitioners build essential martial skills. According to Master Bao, if a student can perform these complex movements fluidly and swiftly, transitioning to traditional stances and techniques becomes more accessible and efficient.

In his experience, many martial artists who first train in modern wushu tend to excel when they later take up traditional styles. The exaggerated movements teach students to engage their whole body, making them more fluid and coordinated. Master Bao explains that in Shaolin, using the entire body for every movement is crucial. While one might perfect punches, kicks, or conditioning exercises, without this full-body engagement, the movements remain stiff and incomplete.

Master Bao observed that sometimes students understand how their body should move, but their body doesn’t respond as expected. For this reason, in China, young students often start with modern wushu or a blend of modern and traditional. Modern styles and methods force them to develop the fluidity needed for martial arts. As they mature and continue their martial arts journey, they often find it easier to learn traditional forms because they’ve already trained their bodies to move with precision and grace. Those who begin with modern wushu and then transition to traditional wushu tend to be more adept than those who exclusively train in traditional forms from the start.

In essence, modern wushu serves as a stepping stone, teaching foundational body mechanics that are essential for mastering traditional forms and styles. While there’s an ongoing debate abroad about the legitimacy of “modern kung fu,” Master Bao believes that it is a valuable training tool—just as real and purposeful as traditional styles—and that the core principles of Shaolin martial arts remain very much alive and thriving today.

Want To Read More?

Stay tuned in the coming weeks for more sections of the article! If you live in Australia and want to support the magazine, check out the digital or printed copy of Martial Arts Magazine Australia (MAMA), Issue 6 on their website.

Disclaimer: We do not receive any financial compensation from the sales or distribution of Martial Arts Magazine Australia, Issue 6, which features the referenced article. Our sole intent is to share our contribution to this publication with our readers.

El wushu tradicional no tiene acrobacias.

El wushu tradicional se enseña con movimientos amplios para aprender la estructura externa y con los años la estructura se vuelve interna logrando así hacer los movimientos más sobrios y con toda la potencia que tendrá un maestro.